CEDAR RAPIDS, IOWA // So much for Iowa Nice. It's more like Iowa Nasty.

In a state where Midwestern civility usually extends to politics, the Republican presidential campaign has become an acerbic affair. Negative ads fill television and radio. Attacks are all over the internet and in material stuffed in mailboxes. Many of the candidates bash each other with abandon.

It's a reflection of the crowded Republican field and the volatile race to emerge as the challenger to the US president, Barack Obama, in November. To the dismay of many voters, it is also probably only going to get worse when there are fewer candidates and the contest moves to New Hampshire, South Carolina and beyond.

"If they go negative, they aren't getting my vote," said Ginger Allsup, 45, a bakery worker in Oskaloosa.

That's a risk campaigns in Iowa are willing to take, given the high stakes and state of the race ahead of today's caucuses that kick off the fight for the Republican nomination.

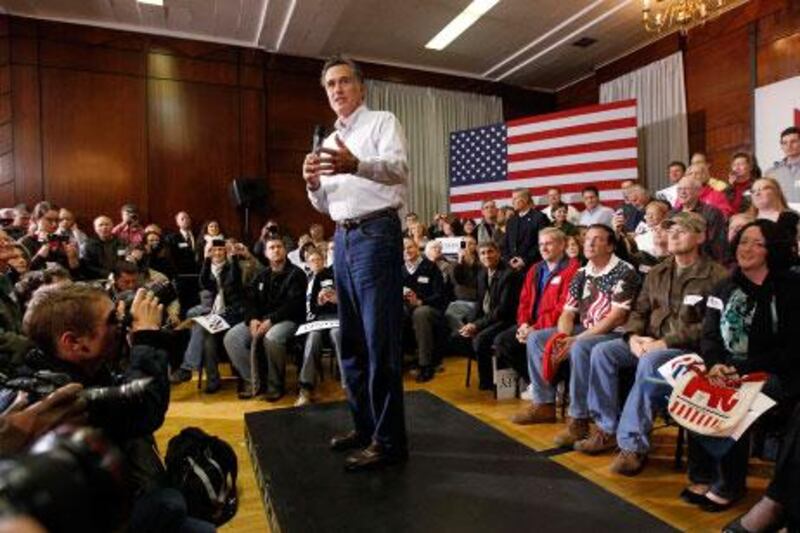

Only three candidates typically make it out of Iowa with enough momentum and money to continue. Polls are showing that most hopefuls are bunched tightly behind the former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney. Desperate to break from the pack, they're whacking away in hopes of sinking opponents and wooing undecided voters.

Usually, presidential candidates and their allies take care to be congenial in Iowa, which has a record of rewarding candidates who stay above the fray. It's a state where campaigns seek to make positive first impressions by promoting their own policies and offering subtle comparisons.

By the time New Hampshire comes around, the field usually has narrowed and those left standing try to differentiate themselves even more, in a sharper and often more personal tone. It only escalates from there when voting turns to South Carolina, which has a long history of go-for-the-jugular politics.

But Iowa is different this year.

It's partly because of a Supreme Court decision that allowed unions, corporations and individuals to spend unlimited amounts of money to advocate for the election or defeat of candidates. As a result, new outside groups, known as super PACs (political action committees), that are aligned with the candidates sprang up. These groups have paid for an avalanche of hard-hitting television and radio ads, as well as aggressive literature in mailboxes and harsh messages online.

What about the candidates? They're hardly holding their tongues. Sometimes, they are using language that Republicans often reserve for Democrats.

"She doesn't like Muslims, she hates them, she wants to go get 'em," Ron Paul, the Texas congressman, said about the Minnesota congresswoman Michele Bachmann. "Dangerous" is how Mrs Bachmann describes Mr Paul's foreign policy.

In other cases, they use humour to try to blunt the force of the attacks.

Asked about Newt Gingrich's failure to get on the Virginia ballot, Mr Romney likened the former House of Representatives speaker's political operations to an out-of-control chocolate factory from a half-century-old I Love Lucy episode.

"Cute" was Mr Gingrich's reply.

He then issued a challenge as he visited a chocolate factory the day after Mr Romney's jab: "Here I am in the chocolate factory. And now that I have the courage to come to the chocolate factory, I hope Governor Romney will have the courage to debate me one on one and defend his negative ads."

There's a reason candidates are assailing each other: It can work.

Consider Mr Gingrich's up-and-down December.

He was flying high in the polls at the start of the month. Then he was pounded by at least US$4 million (Dh14.7m) in negative television adverts in Iowa, most run by Mr Romney allies and some by Mr Paul's campaign.

He was also the target of mailings calling him "a 30-year Washington insider" who has flip-flopped on core Republican issues.

At campaign events, Mrs Bachmann, Mr Paul and others spread those same messages.

"I had been leaning towards Newt," said Jean Fredsall, 67, a retired social worker from Cedar Rapids. "But then I was reminded of his baggage."

But negative advertising also can backfire, particularly in a crowded field in Iowa.

In 2004, Howard Dean and Dick Gephardt were the front-runners to win the Democratic nomination. Looking to seal the deal, each ran blistering ads just before Iowa voted. Both ended up losing voters and the nomination. John Kerry and John Edwards got the coveted tickets out of the leadoff caucus state.

The lesson: Those who run negative ads risk driving up their own negative perceptions in voters' minds.

Republican Mike Huckabee probably was mindful of it four years later.

Rising in the polls just before the caucuses, the former Arkansas governor was the target of criticism. But while pundits called for him to go on the attack, the most Mr Huckabee did was tease a negative ad during a news conference. Then, he shelved it before it ever ran.

"It's not worth it," he said, adding: "It's never too late to do the right thing."

Iowans ended up rewarding him with a caucus victory, though John McCain captured the nomination.

Four years later, that lesson seems lost.