The radical sermons of al-Qaeda propagandist Anwar al-Awlaki helped radicalise an American student setting him on a course that took him to Pakistan where he built a bomb designed to destroy a US military base in Afghanistan, according to prosecutors at the trial of Muhanad Mahmoud al-Farekh.

They summed up their case on Tuesday in a federal courthouse in Brooklyn, New York, saying two weeks of evidence should leave the jury in no doubt of the defendant’s guilt.

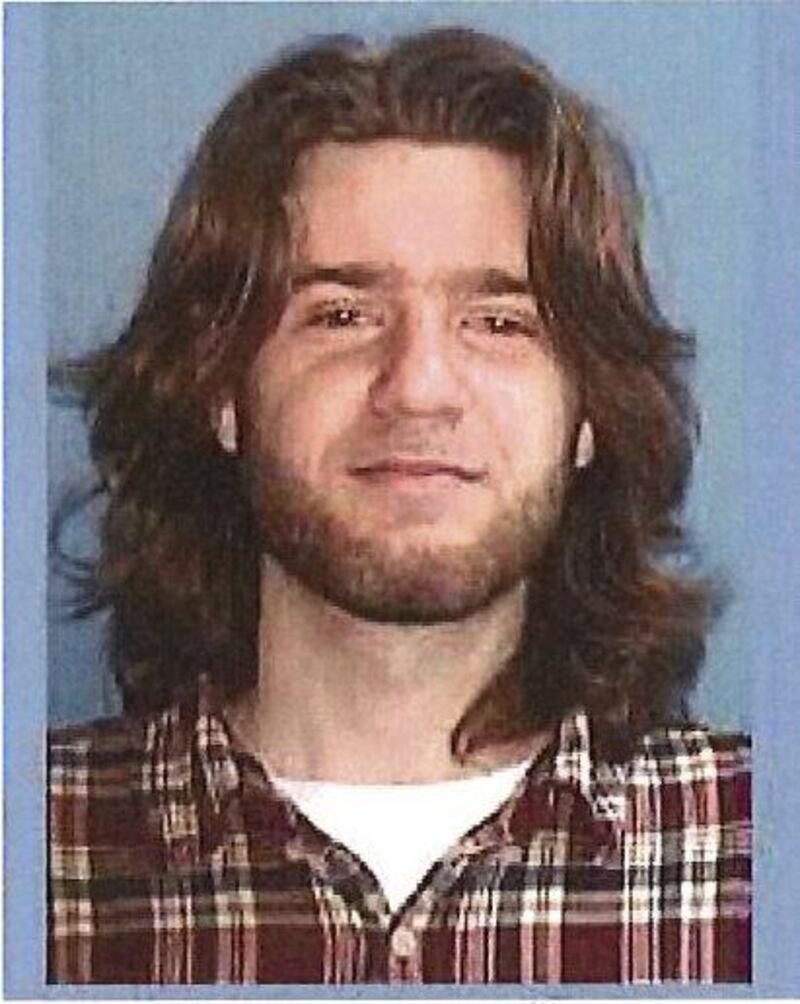

Farekh, 31, who was born in Houston and raised in Dubai, was captured by Pakistani security forces in 2014.

He has pleaded not guilty to nine charges, including conspiracy to murder American nationals, providing material support to al-Qaeda and conspiracy to use weapons of mass destruction.

His defence contends that he is the victim of American government “speculation, fear and politics”, and of a prosecution that “backfilled” the glaring gaps in its case only after he had spent months in Pakistani captivity.

________________

Read more

[ American Al Qaeda suspect 'plotted attacks against the West' ]

[ Trial set to open of American-born Al Qaeda suspect from Dubai ]

________________

The jury is expected to retire to begin considering its verdict on Wednesday.

The defendant’s father briefly interrupted proceedings on Tuesday as he called out to ask the judge for permission to meet his son.

“Can I meet Muhanad,” he shouted as the jury was being led out. “I’m 66 years old.”

He was silenced quickly by Judge Brian Cogan before he could continue.

The prosecution case rests on what it says are 18 sets of fingerprints found on a giant car bomb that failed to explode during an attack on an American military base.

In his closing statement on Tuesday, Douglas Pravda, US assistant attorney, said there was only one explanation for all the evidence.

“The abrupt departure from Canada in 2007, the radicalisation that led him to travel to Pakistan.

“His fingerprints on the bomb... and DNA evidence,” as well as the handwriting on a letter mentioning al-Qaeda and discussion life in Pakistan’s militant haven of North Waziristan, he said.

“There’s only one conclusion that you can draw, that Muhanad al-Farekh joined terrorists, that Muhanad al-Farekh provided material support to terrorists, that Muhanad al-Farekk tried to kill Americans.”

According to the prosecution, two bombs were loaded on to vehicles for an attack on Forward Operating Base Chapman in Afghanistan in 2009. The first exploded as it reached the gate but a second, bigger device was never detonated.

Investigators described during the trial how they painstakingly unravelled packing tape wrapped around 7500lb of explosives.

They said they found fingerprints that matched Farekh’s and, stuck to the tape’s adhesive, a hair dyed orange in the same style as that favoured by the defendant at the time.

The trial also heard how Farekh became interested in the teachings of Awlaki while he was a student at the University of Manitoba.

A witness who knew the defendant at the time and travelled with Farekh to Saudi Arabia for Haj said he was disturbed to discover his friend absorbed in the teachings of the radical cleric.

“He saw Muhanad al Farekh listening to a lecture, a radical lecture, a jihad lecture by Anwar al-Awlaki,” said Mr Pravda, who also cited emails sent by the defendant to his father asking him to obtain the preacher’s teachings.

The American-born Awlaki was killed by a CIA drone strike in Yemen in September 2010. He was a a key al-Qaeda propagandist and his words exhorting Western Muslims to take violent jihad have been used as evidence in dozens of terror trials.

However, Sean Maher, for the defence, said there was no evidence Farekh had listened to anything but a tiny portion of his teachings and that radicalisation was a more complex process than the prosecution suggested.

“When this American government tries to use what we look at, read, think, as being too radical for them, that’s not a place where we want to be,” he said.

The government’s star witness was a former al-Qaeda member with an interest in helping prosecutors in order to win a shorter sentence, and who contradicted himself and other witnesses, added Mr Maher.

“If you look at any part of the evidence it just crumbles,” he continued. “It’s ridiculous.”

Instead he said the case had been constructed to account for a lack of sightings of Farekh from 2007, when he arrived in Pakistan, to April 2015 when he was passed into American custody.

“On fear, speculation, politics, Muhanad al Farekh is here before you,” he said.

No-one had explained how a USB drive, holding letters allegedly written by Farekh, had turned up at the US embassy in Afghanistan in September 2015.

“We get nothing from the government about where this thing came from other than it appeared in the embassy in Kabul,” he said.

And Mr Maher warned the jury against trusting the fingerprint and DNA evidence when agents who gathered the bomb material admitted in their own words that they had been “as expedient as possible” because they were working in a “combat zone”. Nor had they kept a log of Afghan soldiers charged with securing the site.

“There’s nothing the government has brought to show the integrity of the crime scene was protected,” he said.