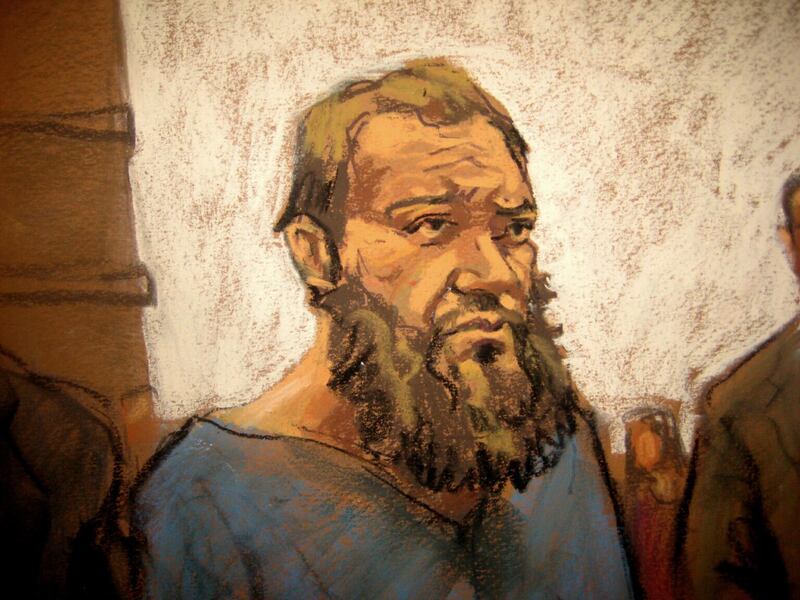

The trial of a major international terrorism suspect was thrown in to disarray on Thursday when it emerged the father of Muhanad Mahmoud Al Farekh approached jurors in New York to tell them he had not seen his son in 10 years.

The extraordinary twist came after the jury had just begun its deliberations after hearing two weeks of evidence including how Farekh’s fingerprints were found on a bomb intended to destroy a US base in Afghanistan.

Farekh's lawyers asked the judge to declare the hearings a mistrial but after hearing arguments from both the defence and prosecution, Judge Brian Cogan ordered four jurors to be replaced with three available alternates and told them to begin their deliberations anew.

Farekh, 31, who grew up in Dubai, has pleaded not guilty to nine terror-related charges and faces up to life in prison.

On Thursday morning Mr Cogan said juror number two reported that he and other members of the jury had been approached by Mr Farekh’s Jordanian father in the lift as they left the federal courthouse in Brooklyn a day earlier.

“I haven’t seen my son in 10 years,” he said, according to the judge’s account. “Do you think that’s fair?”

After interviewing the jurors who had been present in the elevator, the defence asked that all four be removed from hearing the case. However, with only three alternate jurors that would leave a jury of 11.

Sean Maher, for the defence, said the defendant, Farekh, was not waiving his right to a trial with 12 jurors, “which leads me to move for a mistrial”.

Prosecutors contend that Farekh left his studies at the University of Manitoba, in Canada, in 2007 and cut off contact with his family. He was captured by Pakistani security forces in 2014.

However, the defence said the prosecution had offered no evidence that Farekh had not been in touch with relatives.

On Thursday, Mr Maher said one juror believed Dr Farekh said he had not kissed or seen his son in seven years, effectively supporting the government’s case.

“From the defence’s perspective, that’s very troubling,” he said.

Earlier David Ruhnke, another of the defence team, described how he had been contacted by his client’s brother Ibrahim to say “his father had done something stupid”.

He then spoke to Dr Farekh, their father, who said he had asked the jurors: “Do you think it’s fair that I’ve not been able to kiss my son?”

“He told me he’s a very emotional person. He told me that he’s treated for bipolar disorder,” said Mr Runkhe. Dr Farekh also believed his medication had not been effective on the day in question, Wednesday.

Mr Runkhe added that he advised Dr Farekh to stay away from court.

Judge Cogan said the defence arguments were insufficient to justify a mistrial after so much time and effort had been extended.

“This trial has been expensive, extensive and complex,” he said, ruling that it would proceed with a jury of 11.

The US has strict laws against jury tampering and obstruction of justice, carrying penalties of up to 10 years in prison and $250,000 (Dh918,225) in fines.

The trial of Farekh is just the latest high-profile international terrorism case to come through the Eastern District of New York.

The evidence in court included details of how he listened to sermons by the radical cleric Anwar Al Awlaki, one of Al Qaeda’s chief propagandists, before abruptly leaving the University of Manitoba with two friends for Pakistan in 2007. There he took a circuitous route to Peshawar, gateway to the country’s militant havens along the border with Afghanistan, and cut off email communications.

A former Al Qaeda member identified Farekh as the man who took over as head of Al Qaeda’s external operations wing – responsible for plotting attacks against foreign targets - when another senior figure, Abdul Hafeez, was killed in a drone strike.

His alleged role brought him to international attention, under his pseudonym Abdullah Al Shami, long before he was captured.

Pentagon officials and the CIA wanted him included on a kill list, according to The New York Times. However, the US Department of Justice argued against the designation, questioning whether Farekh was sufficiently high-ranking for the administration to justify taking the extraordinary step of ordering the death of an American citizen overseas without a trial.

Much of the evidence against him comes from a botched attack on an American military facility in Afghanistan.

Two vehicles packed with explosives were driven by suicide bombers into Forward Operating Base Chapman in Khost province in January 2009.

Only the first exploded and prosecutors allege that 18 sets of Farekh’s fingerprints were recovered from brown packing tape recovered from the second.

_________________________

Read more:

[ Radical sermons set American on course to join al-Qaeda, say prosecutors ]

[ American Al Qaeda suspect 'plotted attacks against the West' ]

[ Trial set to open of American-born Al Qaeda suspect from Dubai ]

_________________________