For decades, Islamic publishing in the US was a small but steady market, with just a handful of players.

But after the September 11 attacks, interest in the religion heightened, as did enrolment in Islamic studies courses at universities across the United States. Demand for copies of the Quran, biographies of the Prophet Mohammed and other key Islamic texts increased dramatically too, and a million Islamic publishers bloomed.

Or at least a couple of dozen, from personal boutique houses such as Muslim Writers Publishing in Arizona to bigger outfits like Tahriki Tarsile Qu'ran in New York. Today, Chicago remains something of an industry nexus - home to American Trust Publications, established in 1976 and run by the Saudi-backed North American Islamic Trust, and Iqra International Educational Foundation, whose popular Sirah series was first published in 1981.

But the oldest Islamic publisher in Chicago, and perhaps all of North America, is Kazi Publications, which has been producing, selling and distributing books from the city's North Side for nearly 40 years. Despite humble beginnings, the firm's annual revenue has nearly quadrupled over the past decade, from $250,000 (Dh918,000) to nearly $1 million, according to co-founder and proprietor Liaquat Ali.

The seeds of Kazi were planted around 1970, when Ali and his brother-in-law began importing books and handicrafts from Pakistan to sell in the shop of their friend Mahmoud Kazi, on Wells Street near downtown. In 1972, Ali returned to Chicago to run the shop with Kazi.

The duo noticed the rise of the Nation of Islam among local African-Americans and, taking advantage of a family connection to one of Pakistan's leading publishers, began to focus on books. A leading local newspaper soon highlighted their shop as the best spot for Islamic publications. "It was so busy that I didn't know what was going on," recalls Ali. "I asked someone, 'Where did you get the address of this place?' He said, 'Don't you know? It's in the paper.'" Kazi Publications was born.

Mahmoud Kazi soon accepted a teaching job at King Fahd University, in Saudi Arabia, leaving Ali in charge. But before he left, he and Ali noticed a problem. "So many locals were converting to Islam," Ali recalls. "They wanted to name their baby appropriately, but they didn't know what the names were." In 1974, Book of Muslim Names became Kazi Publications' first published work.

A few years later, the original shop burnt down. Ali moved to several locations before finding the shop's current home, on Belmont Avenue, in 1984. No sign hangs from the squat brick building's blue-green facade; Ali removed it after the Lockerbie bombing in 1988 to avoid anti-Islam sentiment. "We have a house in the back," Ali, 64, explains. "I'm living there with my wife, so I got scared."

Only swirling Islamic designs mark the entrance and most days the front door stays locked. Kazi, a non-profit organisation, makes the lion's share of its sales through phone orders from universities and booksellers such as Barnes & Noble and Amazon. "The only customers who come here are people who know the place," says Ali, unlocking the door for a visitor on a recent afternoon.

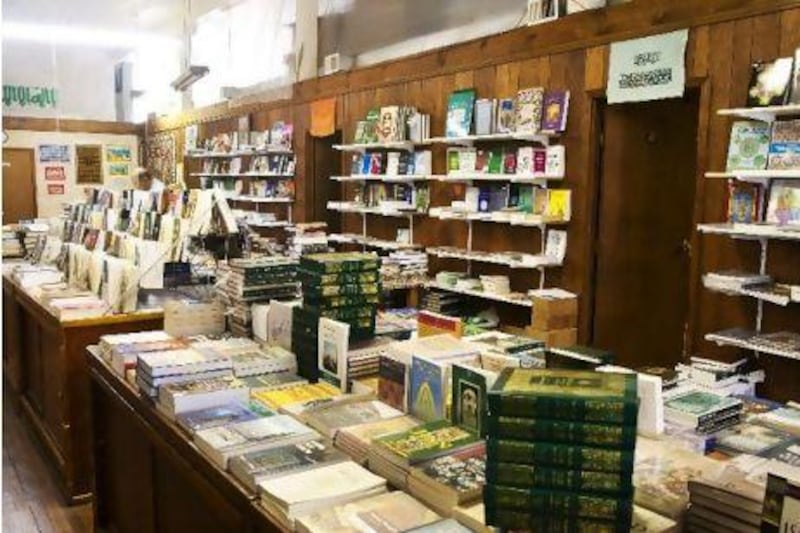

Inside the dusty, cosy space, rows are devoted to the Quran, the life of Prophet Mohammed, Islamic finance and jurisprudence. In the back are books for children, such as the popular Quran Made Easy, and a few shelves of Urdu publications. Among Kazi's bestsellers are the works of Seyed Hossein Nasr, a respected professor of Islamic studies at George Washington University.

Nasr is the mentor of Laleh Bakhtiar, Kazi's in-house scholar and production manager. Born in Iran to an American mother and an Iranian father, the 72-year-old Bakhtiar was raised mostly in Washington.

She married an Iranian-American architect and moved back to Iran with him in 1964.

They had three children and divorced in 1977, and Bakhtiar stayed in Tehran through the revolution and the years of war with Iraq. "My children and I lived for eight years in fear of our lives with daily bombs dropping all around us," she says. In the decades since, she and other Iranian intellectuals have felt acute disappointment as the current leadership has repeatedly failed to live up to the revolution's grand Islamic ambitions. This feeling, she says, fed into the 2009 protests, and continues to undermine the current regime.

Bakhtiar returned to the US in 1988, earned a PhD in educational psychology from the University of New Mexico and gravitated towards writing and researching Islam, particularly Sufism. Visiting Kazi Publications' booth at an Islamic book conference in Bloomington, Indiana, in late 1992, she found the publisher in the market for a book producer.

"They had book distribution at the time, but they didn't have book production," Bakhtiar recalls. "They were driving all around Chicago looking for someone with book production experience - writing and research, typesetting, design, layout - and that was my speciality by then."

She had written and translated several books for prominent publishers, including the University of Chicago Press and Thames and Hudson. "We had done some production, but we weren't capable of sophisticated mainstream publications," recalls Ali. "I told her to come to Chicago and we had a board meeting and we decided what we wanted her to do."

Bakhtiar embraced the job and her new city, writing, editing and translating books and, in her spare time, lecturing on Islam at the Lutheran Theological Seminary, connected to the University of Chicago.

She and Kazi made headlines in 2007 with The Sublime Quran, her semi-feminist translation of the Quran published in early 2007.

The book received global attention - including stories in The New York Times and The Times and on CNN, Al Jazeera and the BBC - in large part because Bakhtiar translated the controversial Chapter 4, Verse 34, to state that a man should "go away" from a rebellious wife, rather than "beat" her, as had long been the most common translation of the Arabic word daraba. There were other alterations as well. Kafir, for instance, often translated as "infidel", Bakhtiar changed to "ungrateful".

The Sublime Quran met stiff resistance from Islamic traditionalists, who argued that Bakhtiar was not a Quranic scholar. Yet the book received a warm reception from many American converts, according to Bakhtiar, who says she received hundreds of positive e-mails. It also won glowing notices from several prominent names, including John Esposito, founding director of the Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding at the Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, and Reza Aslan, author of the bestselling No God But God.

At Christmas 2009, acclaimed author Dave Eggers recommended the book as a gift. "For anyone who wants to know more about Islam, or simply wants to read a beautiful book," he wrote in O magazine, "this really is the most accessible version in English." The book has ridden these recommendations to strong paperback sales, particularly among the Islamic departments of more liberal colleges.

As of this month, both volumes of another key Bakhtiar work, Biographies of Early Muslim Women, are available as e-books. The work is a collection of all the hadiths reported by women, and for Bakhtiar, it underscores the importance of women in Islam, even during the Prophet's time. "When one regular woman can report how the Prophet reported a verse in the Quran, that's the highest kind of knowledge," she says. "Today they say women can't be judges, women can't be this, can't be that, because there needs to be two of them. This shows what women did in early Islam, before jurisprudence was formed. Later, with jurisprudence, women and slaves were declared imperfect."

Bakhtiar is working with 15 female scholars on the first women's commentary on the Quran, parsing each chapter by theme and presenting interpretations according to four levels of religiosity. She hopes to publish it in 2012.

Next year will mark Kazi's 40th year of operation. For Ali, his work and his business have instilled a great deal of pride. "We've never cheated anyone," he says. "We've had no complaints from anybody we've ever done business with." Flipping through letters from convicts in Missouri, Florida and Virginia, he beams while explaining Kazi's habit of sending a few books to correctional institutions whenever a prisoner writes requesting a title. "We send free books to jail libraries all the time, so everybody can read our work," he says.

Kazi's most enduring legacy may be its newly developed great books programme, which presents new translations of seminal works in the Muslim canon. Recent publications include the Alchemy of Happiness, by Al Ghazali, Rumi's masterwork, Mathnawi, and Surabadi's 12th century Quranic commentary.

"We're concentrating now on translations of classic works because the Muslims today in America have lost the connection with their intellectual culture and civilisation, and all they know is the imitation of when you stand in prayer your feet have to be certain inches apart, these kinds of things," says Bakhtiar. "No one knows who were the great philosophers, the great engineers, the great mathematicians, the great scientists, the great writers. They're just not familiar with any of that, so what the great book series does is it opens up people's minds to think for themselves."

David Lepeska is a freelance writer who contributes to The New York Times, Financial Times and Monocle, and previously served as The National's Qatar correspondent. He lives in Chicago.