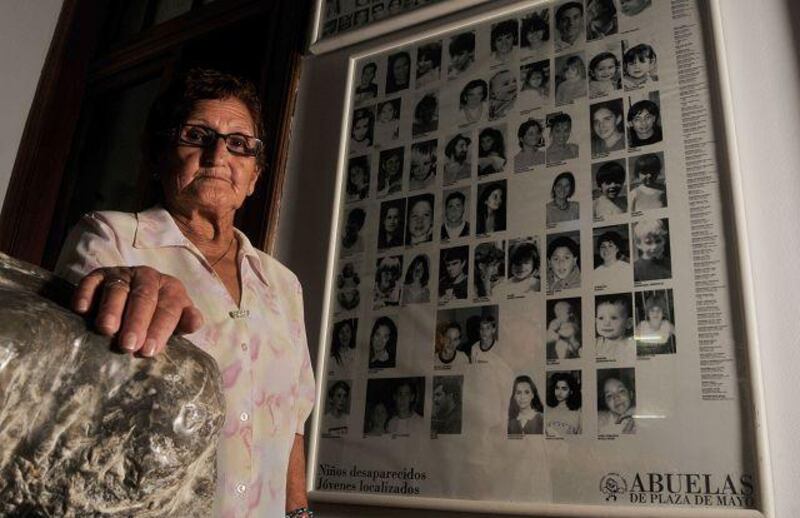

BUENOS AIRES // Irma Rojas sees the faces of the "disappeared" every day. Pictures of "Dirty War" victims look down from her Buenos Aires office wall like a college yearbook, a reminder of the nightmare that once gripped Argentina. Among the faces, some sombre, some with a youthful optimism but all unaware of their impending fate, is that of her then 21-year-old son and his wife, then 20 and seven months pregnant. "At 2am on May 3 1977, the military came, ransacked their flat and arrested them," Ms Rojas said. "I do not know where their bodies are but some prisoners we contacted at the Escuela Superior de la Mecánica de la Armada [the navy engineering school used as an interrogation centre by the regime at the time], said they were tortured. They waited for my daughter-in-law to give birth, then killed her and gave the baby away." Ms Rojas, 73, works with the Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo (Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo), an organisation that searches for children who disappeared under the country's military regime between 1976 and 1982. They employ five full-time lawyers and a psychologist to deal with daily inquiries. In the 1970s Argentina was experiencing widespread civil strife and a faltering economy. Workers' strikes were commonplace and there were a number of bombings by hard-core leftist organisations. On March 24 1976, Jorge Videla, then general of the armed forces, seized power and established a right-wing military dictatorship, initially with significant civilian support, promising to put the country back on track. But the hope of a brighter future soon vanished. One of Videla's first acts was to launch a six-year campaign against political opponents that would come to be known as the "Dirty War", waged principally on people younger than 30 who were considered by the armed forces to be potential political activists or be sympathetic to the Left. The junta, in its bid to crush what it termed "terror organisations" and guerrilla activity, cracked down on any political dissent and imposed a reign of terror on the civilian population, including all political opposition, trade unionists - who accounted for half of the victims, according to court records and rights groups - and students. An Argentine court would later condemn the Dirty War as a crime against humanity. Young people were "disappeared" by the thousands from their homes and such public places as restaurants, cinemas, the street or even places of work. Other civilians and even those within the regime who protested what was going on around them also risked being "disappeared". The new regime clamped down on civil liberties and human rights, drugging dissidents and dropping them from aircraft into the Atlantic Ocean and using electric prods on prisoners, according to rights groups. Security forces would rape women - dissidents and ordinary civilians - while forcing relatives to listen to their screams. Amnesty international and other organisations, as well as historians and researchers, say at least 30,000 were killed or "disappeared" in this way before the military was forced from power after their invasion and defeat in the Falkland Islands in 1982. Ms Rojas's Abuelas organisation achieved its first breakthrough in 1984 when the first stolen grandchild, Paula Logares, who had been taken from a disappeared mother, was discovered in Uruguay living with a man who had been a police chief under the Videla regime. Ms Rojas also discovered her own missing grandchild. After the Logares case a national television campaign was launched urging people who might have had any doubts about their parentage to contact the National Bank of Genetic Data, which the Abuelas had persuaded the post-military government to establish. The bank, which will operate until at least 2050, helps missing children from the Videla era track down relatives. So far, the grandmothers have traced about 100 of the estimated 500 "stolen babies". Among those who had doubts was Ms Rojas's missing granddaughter. "She saw the TV campaign and her stepfather gave her total support in tracking down her parents' identity. He had adopted her in good faith from a hospital, not knowing that her parents had been killed but he too had his suspicions." On July 28 2007, Ms Rojas finally met her granddaughter. "It was a beautiful moment. We hugged and cried and she said, 'Grandma, I want to get to know you and to hear about my parents'. We are in contact now every day." The most famous "missing baby" is the congresswoman Victoria Perez, 31. Her parents were killed after her mother, who had been kidnapped, gave birth at Esma in Aug 1977. "It is important to remember that this was not a civil war," Ms Perez said in an interview. "The term implies two roughly equal sides. The 'Dirty War' was state terror. The military had a social and economic plan to impose and that's why they targeted the political opposition." But Ms Perez said there is no chance of such a regime returning in Argentina. "People are more aware of their rights today than was the case 34 years ago. But we must teach our children about what happened. It is important not to forget." Hundreds of human rights trials are currently under way after a blanket amnesty for members of Videla's military was repealed in 2005, but a combination of a slow judicial system and delaying tactics on the part of defendants has led to frustration. "We want truth and justice. We want people to know," Ms Perez said. tclifford@thenational.ae

In search of Argentina's lost babies

During the country's "Dirty War", young people were "disappeared" by the thousands from their homes and public places.

Editor's picks

More from the national