The first crates of surgical masks and testing kits left China on Sunday, bound for the US where a bungled coronavirus response has delayed the diagnosis of new cases.

Chinese businessman Jack Ma, the founder of technology giant Alibaba, pledged to donate 500,000 tests kits and a million surgical masks to the US, which is scrambling to regain lost time in testing for the virus.

Doctors say the lag has allowed chains of infection to develop as the caseload continues to mount with the number of confirmed cases reaching more than 14,300 on Friday afternoon.

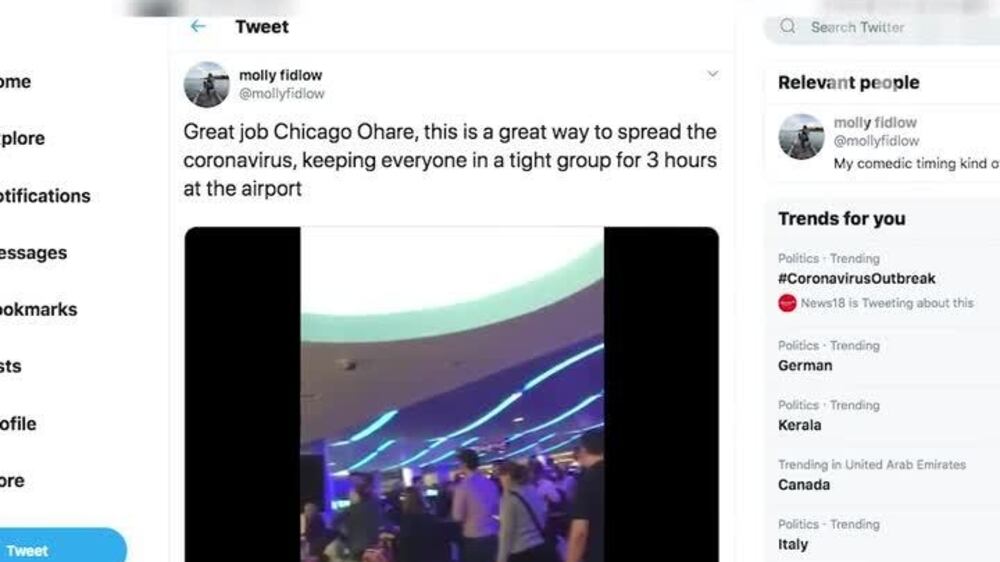

Chaos grips major US airports

Rapid diagnosis is an important step in inhibiting the spread of the virus and monitoring the progress of the disease, Dr Mohamad Mooty, chief of infectious diseases at Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi, told The National.

“The delay to identify confirmed patients with Covid-19 will potentially contribute to the pandemic by having more transmissions. One proposition to make up for the lost time is to be vigilant in the isolation/containment process,” he said.

The Trump administration’s failure to draw lessons from smaller countries that implemented widespread testing early on has drawn criticism from commentators frustrated by the slow response.

As South Korea pioneered drive-through testing and Singapore conducted more than 2,000 tests a day, Washington got off to a false start.

It was not until March 3, six weeks after the first US case was confirmed on January 21, that federal restrictions on testing for the coronavirus were lifted, but the initial kits turned out to be faulty. By this point, the World Health Organisation had already shipped its tests – which the US reportedly rejected – to nearly 60 countries.

In recent days, testing in the US has increased but still only meets a fraction of demand.

"Testing was the first level of defence … the testing was slow nationwide, we're now ramping up in this state," Andrew Cuomo, the governor of New York, told The New York Times this week.

But the damage of delaying the response has been done and the virus has now reached all 50 states. “Testing is no longer going to keep the genie in the bottle, the genie is out of the bottle now,” Mr Cuomo said.

He painted a bleak picture of what could come next.

By one projection, in which the peak of the pandemic is about 45 days away, available hospital beds would fall short of anticipated demand by more than 50 per cent while intensive care units only offer about 3,000 beds for an expected 37,000 coronavirus patients that may need ICU support, he said.

The importance of early testing has been reinforced by healthcare specialists around the world as countries try to contain the spread of a pandemic that has reached a quarter of a million cases and killed more than 10,000 people.

“You can’t fight a virus if you don’t know where it is. Find, isolate, test and treat every case to break the chains of transmission,” the WHO’s director general, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, said at a briefing last week. He reiterated the message on Monday, calling for countries to “test, test, test”.

In South Korea, which has tested more than 290,000 people, the number of new confirmed cases remained below 100 for three consecutive days, down from 909 at its peak in late February. The country has conducted 3,692 tests per million people, compared with five per million in the US, where around 60,000 tests have been run by public and private labs in a country of 330 million, federal officials said on Tuesday.

In the UAE, 127,000 people have been tested so far for the disease, amounting to 13,020 tests per one million people.

As many as 96 million people could be infected in coming months, according to a projection prepared for the American Hospital Association by Dr James Lawler, an infectious disease expert at the University of Nebraska Medical Centre. Of those, 480,000 could die in this scenario.

Developing and distributing test kits is a challenging process. The tests themselves are extremely sophisticated and about 99 per cent reliable, but results have to be determined in a laboratory, which takes at least four hours, Dr Norbert Nowotny, professor of virology at Mohammed Bin Rashid University of Medicine and Health Sciences told The National.

“At this point, increasing the number of people being tested is extremely important,” he said, pointing to the high number of cases in Italy, which has experienced the worst outbreak in Europe. “There comes a point where if you have a certain high number of infections then it is very difficult to contain, so the message is really clear – to increase the number of people being tested.”

Countries in Europe and the US are now bracing themselves for the peak with the true number of infections likely to be far higher than confirmed cases.

The Middle East’s worst-hit country, Iran, faces the same problem. Rick Brennan, WHO’s regional emergency director, said the reported number of cases could represent only a fifth of the real figures. “We’ve said the weakest link in their chain is the data,” he said. “They are rapidly increasing their ability to test, and so the numbers will go up."

In the US, a country at the forefront of biomedical research, people are demanding answers. In a public letter to Vice President Mike Pence, US Senator Patty Murray demanded “an explanation for why the Covid-19 diagnostic test approved by the World Health Organisation was not used”.

At a committee meeting earlier this month she echoed the frustration many Americans have been voicing over social media. “The administration had months to prepare for this – it is unacceptable that people at risk of infection in my state and nationwide can’t even get an answer as to whether or not they are infected. To put it simply, if someone at the White House or in this administration is actually in charge of responding to the coronavirus, it would be news to anyone in my state.”