In 1995, most Dayton residents’ knowledge of Bosnia stemmed solely from the violence they saw of war on the TV news. But when in October that year the city was chosen as the site for crucial peace negotiations, that started to change.

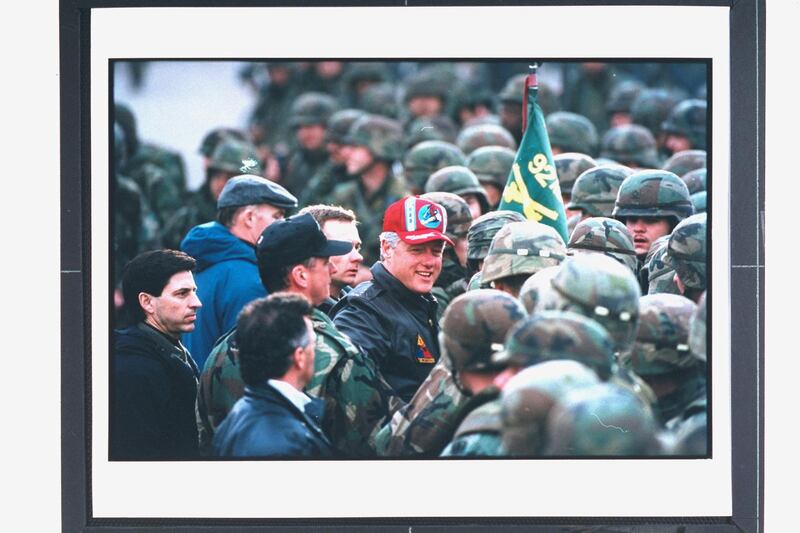

The Wright-Patterson Air Force Base on Dayton’s eastern fringes played a pivotal role in ending the brutal Yugoslavian war, which tore southeast Europe apart and saw ethnic cleansing and the genocide of Bosnian Muslims in Srebrenica in July 1995.

For decades, Dayton had struggled. A small manufacturing-centred city, its citizens were gradually moving away as its factories closed down. But as the eyes of the world looked on hoping for an end to hostilities 25 years ago this month, a feeling of change grew.

“I remember this sort of buzz in the air, this excitement of, ‘Wow, can this really be happening right here?’” said Lisa Wolters, who was in her mid-twenties in 1995. Nine years later, she went on to co-found the Dayton International Peace Museum.

“I was sort of in awe of the whole thing. It felt like we’re a part of this in some small way. At various times they [the political leaders and negotiators] left the base and there was talk about various spottings around the Dayton area. There was this anticipation about what was actually happening.”

Physically separated from the outside world while garrisoned inside the base, the Serb, Croat and Bosnian delegations could neither communicate with the media nor be fully comfortable spending a long period of time in such an austere military environment – something the American negotiators hoped would help the warring factions to find common ground.

As the political leaders entered the base to begin talks, local resident Christina Dull, now 86 and also a co-founder of the Dayton International Peace Museum, wanted to make a grand gesture to people back in Bosnia. “I played the cello well at the time, and decided to play Tomaso Albinoni’s ‘Adagio in G minor’ at the entrance gates as the three [Bosnian, Croat and Serbian] leaders arrived,” she said.

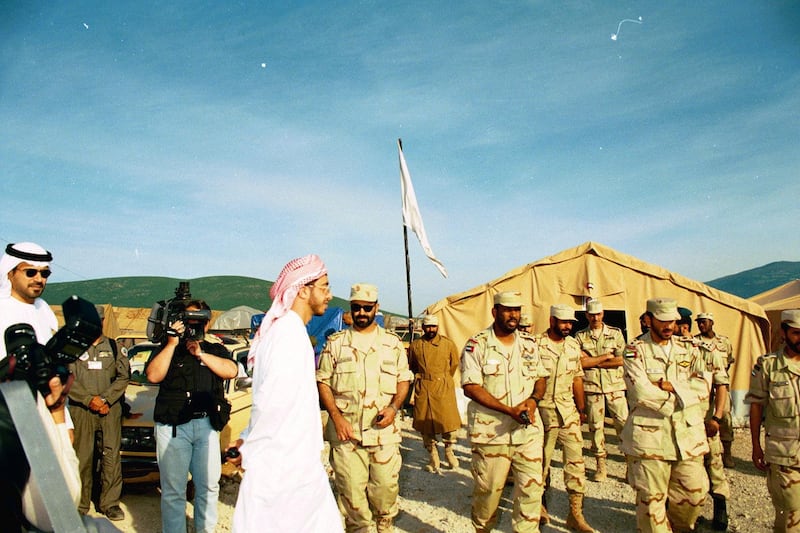

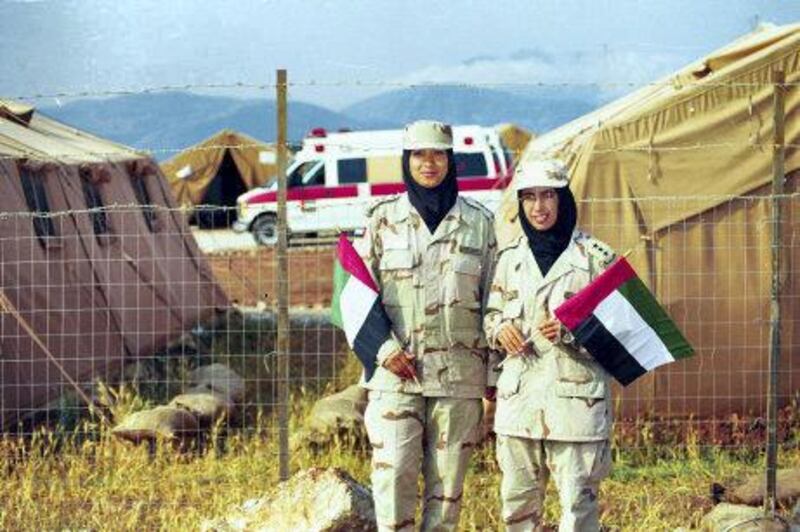

The day Emirati troops came to help war-torn Kosovo – in pictures

Her aim was to make a direct connection between the people of Dayton and those watching on from Bosnia in a way that went beyond words or headlines or images: in Sarajevo at the same time, cellist Vedran Smailovic risked his life to play the same composition at the scene of bombings and funerals as the city laid besieged by Bosnian Serb forces. Months later, Christine and her husband Ralph would themselves travel to Sarajevo.

Inside the base, US negotiating teams and leaders anticipated that a deal could be reached from the outset, but that didn’t mean it would be straightforward.

The lead US negotiator, Richard Holbrooke, whose name is now commemorated on the Hope Hotel, where some of the negotiations took place, took former Bosnian prime minister Haris Silajdzic on long walks around the base. He told him the US would suspend plans to train and equip Bosnia's security forces if his team didn’t push for a resolution.

“It was like being at summer camp with people who just wanted war. It was weird,” says Daniel Serwer, who served as a US coordinator for the Bosnian Federation during the negotiations.

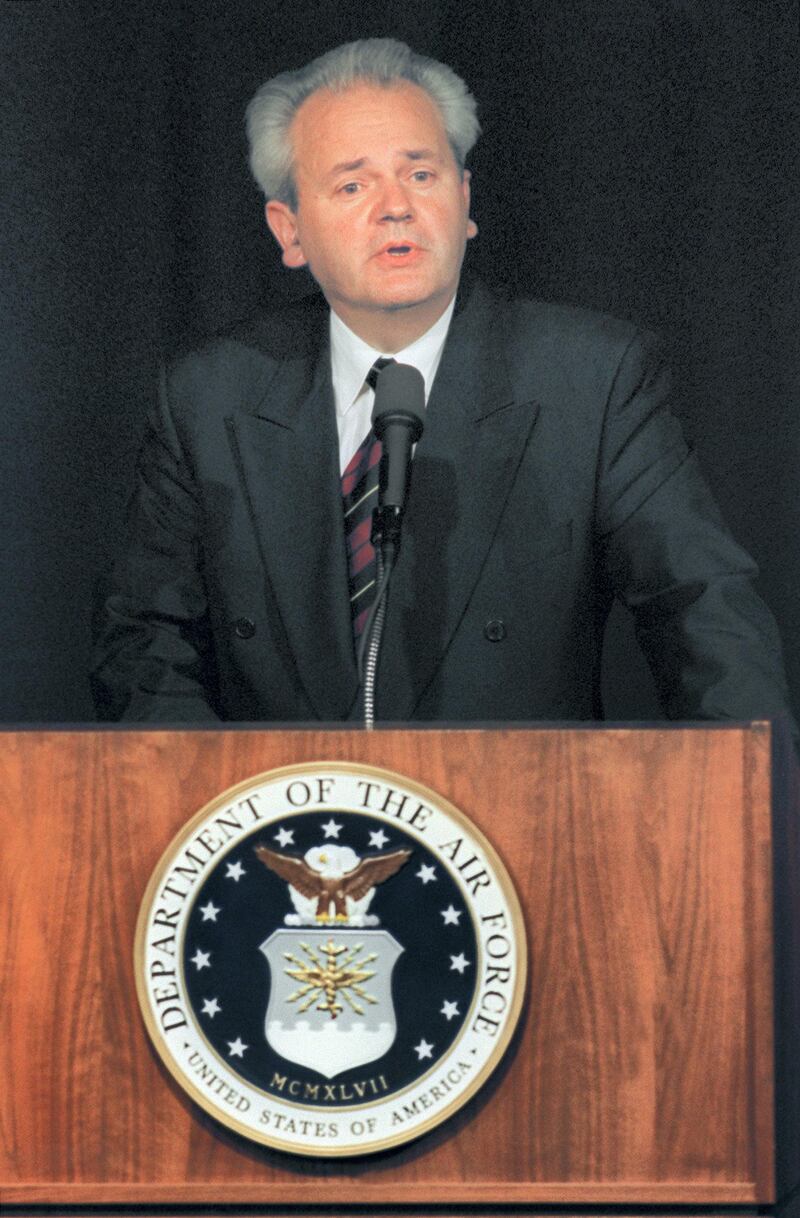

Many of the late-night breakthroughs with Serbia's former president Slobodan Milosevic came over meals of shrimp and steaks at an on-site eatery.

“We would all go to Packy’s Sports Bar, most people preferred it because there were these giant screen TVs – something still new in that era – and they would watch America’s Funniest Home Videos,” says Mr Serwer. “You would try to talk to (the Bosnian delegation), and they’d say ‘no, I’m watching!’”

Despite rare moments of levity, the negotiations were very serious indeed.

"They would rarely go into the same room with each other.”

One of the major sticking points was establishing which areas would be controlled by Bosnians and which by Serbs, with Mr Milosevic repeatedly producing sketched-out maps that were completely unpalatable to the other side.

Negotiators worked late into the cold Ohio winter night on election laws, the status of Sarajevo, the Bosnian capital that had been besieged for over three years, and on eastern Slavonia, a majority-Serb region in eastern Croatia. They discussed sensitive but essential changes to the Bosnian constitution.

While critical to reaching any agreement, the broader constellation of international actors and interests made the negotiations hard going. Russian representatives wanted a say in the make-up of the postwar international peacekeeping force in Bosnia, while the White House, the Pentagon, Nato and the United Nations all had interests at stake, too. European negotiators headed by former Swedish prime minister Carl Bildt were angered at being cast aside by the Americans. There was rancour, too, over the proposed investigation of suspected war crimes committed by soldiers, while the Bosnian delegation found itself at times split.

Twenty-one days after arriving in Dayton, an agreement was reached, despite having come within 20 minutes of failure, according to Mr Holbrooke's memoirs.

Bosnia-Herzegovina would become a single state but divided into the Muslim-majority Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, which made up 51 per cent of the territory, and Republika Srpska, inhabited by Bosnian Serbs in the east and north. The terms were difficult for the Bosnian contingent to swallow.

Looking back now, some of those closest to the coalface of negotiations recall certain regrets.

“We all thought [the proposed peace deal] was a house of cards and wouldn’t last, so why risk my career on a proposition that I was pretty sure wouldn’t work anyway,” says Mr Serwer. “If I had it to do over again, I would have objected more loudly [to the unfavourable terms received by the Bosnian Federation].”

Despite that, today the legacy of this imperfect peace deal is alive and well in Dayton itself. Its residents have been inspired to create a hub of peace movements and non-profits, borne out of its role in helping end Europe’s most violent conflict since the Second World War.

The International Cities of Peace, a non-profit established in 2009 by Dayton resident Fred Arment, connects community leaders in more than 300 cities around the world working towards conflict resolution. The aforementioned Dayton International Peace Museum, the Salem Avenue Peace Corridor, the Dayton Literary Peace Prize and several other initiatives have all been established in the aftermath of the successful Bosnia negotiations.

And almost 8,000 kilometres east of Dayton, in Sarajevo, businesses in the Bosnian capital, including a butchery, still bear the Ohio city’s name today.

All the while, that the Accords still hold today – they were, at the time, meant as a stop-gap solution – is something of a minor miracle given its imperfections.

“Look,” says Mr Serwer, “it ended a terrible, terrible war.”

![“We would see four seasons [in a day], from cold to hot to warm weather," says Col Yousef Al Harmoudi. Courtesy: Maj Gen Obaid Al Ketbi](https://thenational-the-national-prod.cdn.arcpublishing.com/resizer/v2/76FNDBJYQABBWIQJWBA5KNWN5Q.jpg?smart=true&auth=3c5136b23a4573955969faf3dc5a0990be486ccdfb666ffc3c7da79fb5b16ab0&width=800&height=539)