WASHINGTON // The arrest warrant issued last week by the International Criminal Court for Sudan's president, Omar al Bashir, has left the United States in something of a difficult spot. While both the Obama and Bush administrations have accused Mr Bashir of genocide in the past, the United States has never signed on to the ICC or recognised the court's jurisdiction.

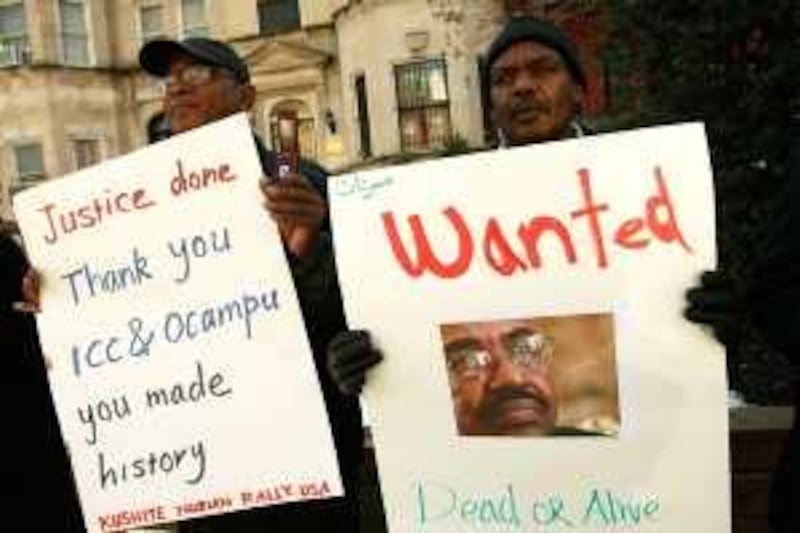

The charges levied against Mr Bashir, which include war crimes and crimes against humanity, are the first brought by the ICC against a sitting head of state and they have sparked opposite reactions in different parts of the world. The African Union and the Arab League, which includes Sudan, have denounced the move and are lobbying for a delay in implementing the arrest warrant. Western democracies, including France and the United Kingdom, however, have cheered it as a bold step for the fledgling court, which so far has taken on only a handful of cases and is vying to gain credibility.

The United States, meanwhile, has been walking a tight rope, on one hand trumpeting the charges as a victory for human rights and on the other trying to minimise the fact that they were meted out by a court it has largely shunned since it was established in 2002. "It is a bit awkward ? it opens them up to charges of hypocrisy or of a double standard," said Richard Dicker, director of the international justice programme at Human Rights Watch in New York, who nonetheless noted that the United States has warmed to the ICC in recent years. "But I think that they can they can overcome some of that awkwardness through some frank and clever phrasing as to their support and commitment for the court."

Since Wednesday, officials in Washington have tried their best to do just that, albeit with some difficulty. In his daily briefing, a US state department spokesman, Gordon Duguid, referred to Mr Bashir as a "fugitive from justice", though he was quickly forced to backtrack by reporters who wanted to know if that meant that the United States recognised the court's charges. "He's a fugitive from justice in the eyes of the ICC," he said.

When pressed further still on whether the United States recognised the ICC's jurisdiction, Mr Duguid carefully skirted the question. "We recognise that by the international community, this has been a move that will try and help resolve the problems in Sudan," he said. "The United States also believes that crimes against humanity have been committed in Darfur." The case of Mr Bashir generates tough questions for the White House that have been debated by human rights advocates and international legal scholars since the presidency of Bill Clinton: should the United States sign on to the world's only criminal court? Can the United States embrace the court's rulings without becoming party to it?

The United States has refused to fully sign on to the ICC, based in The Hague, Netherlands, because it fears that US soldiers and leaders - including presidents - could be subject to prosecution there. The US constitution yields to no higher authority. In the final days of his presidency, Mr Clinton signed on to the Rome Statute that established the court, though the US Senate never ratified the treaty. Still, the president's signature was an implicit guarantee that the US would not interfere with the court's proceedings. In the run up to the Iraq war, however, George W Bush ordered the presidential signature withdrawn.

Many believe Mr Obama will take a less harsh approach to the court, though no one is suggesting yet that he will suddenly shift course and sign on. Top officials within his administration, including his secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, have voiced concerns over provisions that would appear to trump the US legal system and disproportionally affect the US military, which has more troops deployed abroad than any other country. Still, Mrs Clinton declared in a statement during her confirmation hearing that "we will end hostility towards the ICC".

John Washburn, of the American NGO coalition for the ICC, a New York-based umbrella group of non-governmental groups hoping to achieve full US participation in the court, said a formal recognition by the United States would provide a much-needed boost to the judicial body's authority. "The support and backing of the United States will help make the court more effective? [the court] would have wider reach and a better chance of enforcing its arrest orders if the United States was on board," said Mr Washburn, adding that he hoped Mr Obama would engage in an upcoming UN review of the ICC, which is scheduled for 2010.

But others such as Michael Newton, a law professor at Vanderbilt University, say the United States has no need to subject itself to the legal proceedings of an independent court that operates outside of a system of check and balances. "The court is not under the supervision of any external body; it's like a self-contained independent entity, and that cuts against the very foundations of American political philosophy," he said.

"The US position is that we have a fully-developed, functional legal system. Great if some countries want that added layer of the ICC, but we don't need it," he said. "I mean could you imagine a US president who committed genocide and didn't get punished for it? It's inconceivable." Mr Newton, who is serving on a panel assembled by the American Society of International Law that is investigating the US relationship with the ICC, touted what he called the United States' "positive engagement" with the court. He pointed to a 2005 Security Council resolution that originally referred the situation in Darfur to the ICC. The United States considered using its veto power to block the measure, but ultimately decided to abstain.

"There's a pragmatic acceptance that the ICC has a valuable role to play in the international dialogue today," Mr Newton said. sstanek@thenational.ae