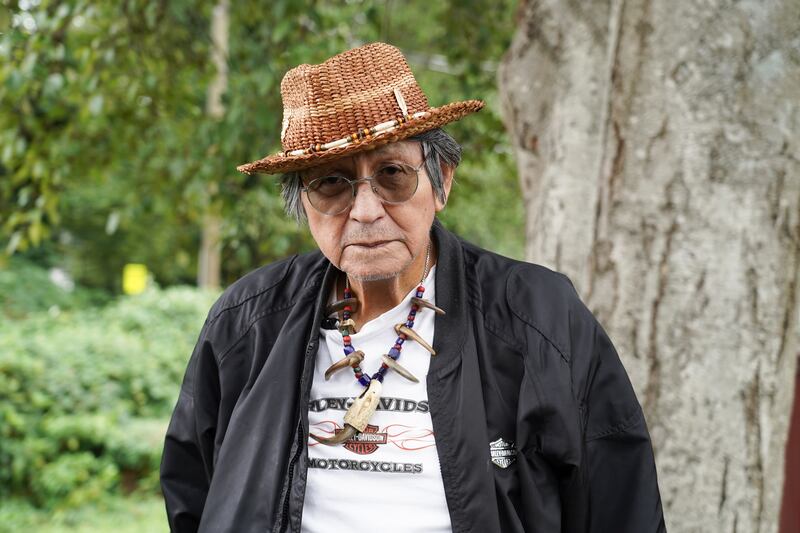

Sam George stands on an embankment and points to an old, rusted shipping container behind the St Thomas Aquinas Regional High School in North Vancouver.

“Right about there, where that container is, is where my brother and I dug the hole,” Mr George, 77, recalled.

For decades, the memory was buried deep inside the mind of the Squamish Nation elder. But in May of 2021, when the Tk'emlups te Secwepemc First Nation announced the discovery of the remains of 215 children at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, everything came flooding back.

Mr George attended the St Paul Indian Residential School from 1952 to 1959. One day, a nun grabbed him and his brother and told them to dig a hole that was the size and depth of a grave.

When they questioned her, the nun told them to “shut up” and to keep digging.

When he heard of the discovery in Kamloops, he came to the grim realisation that he had probably been digging a grave for one of his schoolmates.

Mr George bears the emotional and physical scars of a childhood stolen by the Canadian government and the Catholic Church.

He is deaf in his right ear from being hit in the head by the nuns who ran the school, and six decades later, he still has ringing in his left ear.

“There was a lot of verbal abuse, 'stupid, ugly, savage, dumb Indian', whatever they could think of, all while they were pulling our hair or punching us,” he told The National.

The abuse did not stop there. Mr George said one of the nuns sexually assaulted him repeatedly over a two-year period.

“Everything she did to me, or made me do to her, they told us, if you do this or do that you're condemned to hell before you're married, so I was condemned to hell,” he said.

It has taken Mr George most of his adult life to come to grips with the abuse he endured. For years, the pain drove him to alcohol and drugs, a common response for survivors of the residential schools, said Angela White, executive director of the Indian Residential School Survivors Society.

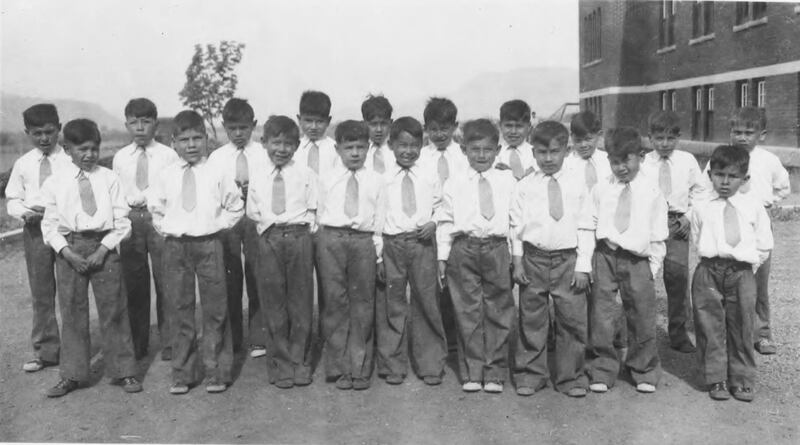

For more than a century, beginning in the 1800s and continuing to 1996 when the last residential school was closed, the Canadian government, often with the help of the Catholic Church, operated a large network of schools designed to forcibly assimilate the country's indigenous peoples.

Children, some as young as 3, were taken from their homes without their parents’ permission and left at boarding schools where they were not allowed to use their native languages. Punishments for disobedience were often severe and sexual abuse was rife.

For decades, the federal government and much of Canadian society ignored the horror stories coming from the schools, and even after the federal government launched a National Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which heard the evidence of thousands of survivors, the country still largely brushed off the issue.

Since the grim discovery in Kamloops, the remains of more than 1,000 indigenous children have been found at former residential schools across the country.

“What [these discoveries] have done, respectfully, is tell the world, ‘you've heard our stories, now this is the physical evidence, and you need to ensure that you believe that our stories were truthful,’” Ms White told The National.

“There is no more hiding behind policy legislation or these very fancy words of reconciliation.”

First Nation chiefs urge action as election nears

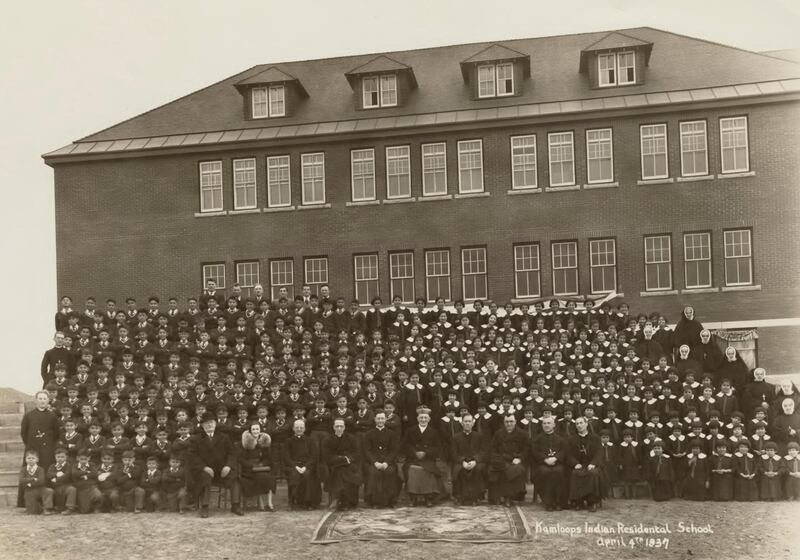

Perched on a hilltop above a bend in the South Thompson River, the Kamloops Indian Residential School still stands in the small British Columbian city. At its peak, it was one of the largest residential schools in Canada, with up to 500 pupils living there at a time.

While the school ceased operations in 1978, the Tk'emlups te Secwepemc First Nation chose to preserve the three-storey red brick building, reclaiming the space as their own.

A stone monument with the names of some of those who were forced to attend the school stands near the building's entrance.

After the discovery of the children's remains, community members placed dozens of stuffed animals and shoes at the foot of the monument.

The graves were discovered through the use of ground-penetrating radar a few hundred metres from the school building, in a field behind the First Nation’s administrative offices.

In accordance with Tk'emlups te Secwepemc beliefs, the area is off limits to the public, protected by metal fencing.

Three months after the grim discovery, the community is still demanding accountability.

“I think the community today is past the grappling stage and now they're basically looking at the path forward and what that's gonna look like,” said Rosanne Casimir, chief of Tk'emlups te Secwepemc First Nation.

Chief Casimir and other indigenous leaders believe that addressing the atrocities of residential schools should be a top priority for the current Canadian election campaign.

“All levels of government must work with urgency on the issue of the burial sites across this country and in finding ways to heal the trauma that our peoples have experienced for generations,” said Chief RoseAnne Archibald of the Assembly of First Nations.

While indigenous issues have been brought up during the month-long campaign and were a topic during last week’s English-language leaders' debate, many believe First Nations communities are not receiving enough attention.

All five of the party leaders vying to be prime minister have said they are for reconciliation, but have shown little in the way of concrete plans to achieve it, something that has frustrated indigenous leaders for years.

“The kind of action that I want to see from them is truly working through the steps of the calls to action, truly looking at ways to be ending racism and discrimination, truly working with First Nations, you know, as individuals as real people, not as individuals that need to be taken care of as per the Indian Act,” Chief Casimir told The National.

She believes the Indian Act, a law that dictates the way the government interacts with the First Nations, should be abolished.

For people like Mr George, no government action will ever be enough to heal the scars he bears from his experience at the residential school.

“I've seen so many broken promises from the government … Lots of lies, lots of broken promises,” he said.

But Mr George has found solace in the outpouring of support from non-indigenous Canadians following the discoveries at Kamloops.

He hopes that nationwide outrage will one day translate into better relations between the First Nations and the federal government.