CANNES, France // A Syrian woman whose horrifying footage of the siege of Homs was turned into a film by an exiled director received a standing ovation at the Cannes Film Festival on Friday.

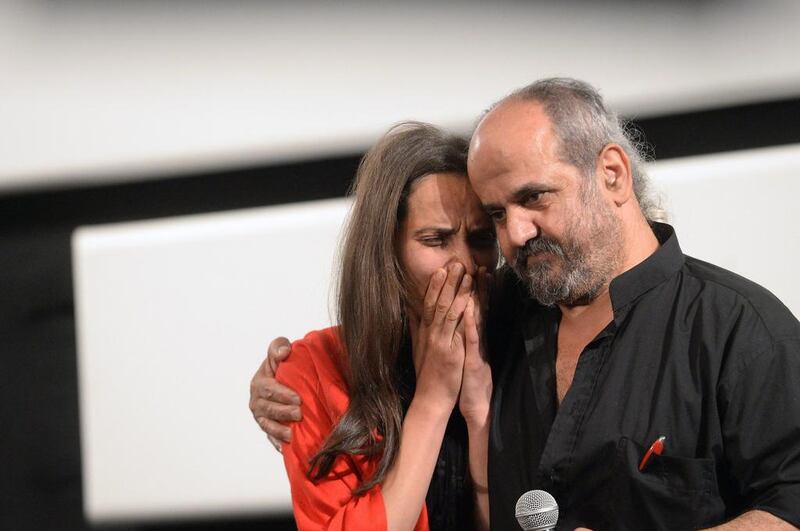

Documentary maker Wiam Simav Bedirxan put her head in her hands and had to be comforted by director Ossama Mohammed, whom she met for the first time a few hours earlier, as the audience applauded her arrival for the film they made together, Silvered Water, Syria Self-Portrait.

The meeting marked the close of an extraordinary chapter in each of their lives – in which he escaped Syria with his life but suffered from survivors’ guilt in exile in Paris and she returned to her family in the besieged city of Homs armed with a video camera.

Mohammed, who has twice before brought films to Cannes, said he felt he had been given a second chance when Simav contacted him one day out of the blue from Homs asking what he would do in her position.

“Simav saved me, she really saved me, she saved my life. Syria made her remember about Ossama and believe that he could help,” said the filmmaker, who comes from the Syrian province of Latakia.

“It was a very painful time for me, feeling that I [was] first in Damascus and second Paris, feeling that I’m saved, maybe, but psychologically I was not saved.

“I was not sleeping. I [thought] OK, I had an illusion that I was [a] brave defender of truth, of human rights, but I’m defending it from my room in Paris,” he added, speaking in his second language English.

Over the following months, Berdixan sent more and more footage over the internet to Mohammed, who started to construct the film using the images combined with their email exchanges.

In the film, Berdixan describes how after her return to Homs she finds herself in a flat with “the remains of who I am” and “my old father crying like a cat”.

Each day she goes out to film protests against president Bashar Al Assad’s regime, shootings, bodies. She also obtains footage from defecting soldiers of torture and killings.

One day she films two veiled women being grabbed in the street and dragged away by unidentified armed men.

“Will I die of torture in the basement of a militia leader?” she asks, out of sight of the camera.

Eventually soldiers come to her neighbourhood and shout orders for everyone to leave.

“I bid him [father] farewell [and] on legs made of wind I run. A single look back would have killed me. I saw mum fall and she didn’t get up,” she says.

Others in the film are anonymous to the viewer, although some are known to Berdixan.

In one scene a group of mostly middle-aged women flee in panic down a country road.

“Abdo was burned!” one shouts. “Nobody’s left, there’re mass graves!” another cries. “Damn you Bashar.”

A young man carrying a child drops to his knees and jabs his hands at his forehead in disbelief.

The viewer is not told who Abdo was, whether the child was dead or injured or where the women went.

Another scene follows a young boy, aged about five, who takes flowers to his father’s grave.

“I brought you the best rose ... I miss you,” he says, addressing the grave in a matter of fact way.

“Mum look how deep this grave is,” he says later as he wanders nearby.

Cut to another scene and he walks through wasteland and deserted rubble-strewn streets. “Look there’s a flower!” he exclaims.

As he approaches a road junction, he tells Berdixan, “Here there’s a sniper” before reassuring her, “he’s not shooting”.

Mohammed said that as more and more images arrived in his inbox from Berdixan he found himself gripped with suspense.

He realised that she had opened up a “virtual route” via which he could play his role in the uprising and every day he waited, full of anticipation to see what new images she would send him.

The Syrian conflict, he said, had been almost unique in terms of the sheer number and the nature of the images captured by ordinary people, rather than professional journalists.

“Since the first moment this was a revolution of images ... it was Syria screening itself each day,” he said.

Making the film, however, meant difficult choices such as how to choose the “best dead body shot, the most beautiful martyr”.

But he said he steeled himself because he believed the Syrian regime wanted to destroy the story of each individual that opposed them and that his film could give them a voice.

*Agence France-Presse