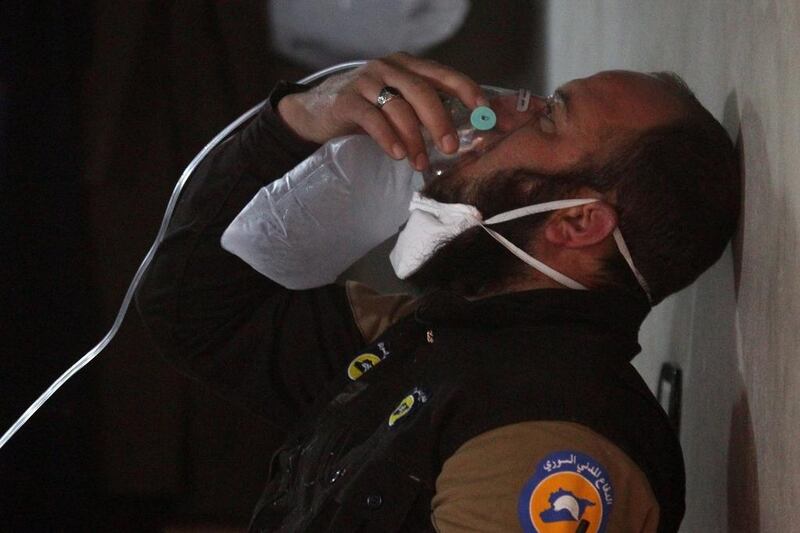

BEIRUT // First came the reports of a chemical strike in a town unfamiliar to all but the keenest Syria observers. Then came the chilling videos of civilians gasping for air, as they lay dying on the ground next to corpses. They included images of ashen-faced children lying among piles of bodies – maybe dead, maybe alive. And a few hours later, jets bombed a field hospital where those lucky enough to survive the chemical attack were being treated.

If Tuesday’s attack on the rebel-held town of Khan Sheikhoun in Syria’s northwestern Idlib province seemed familiar, it’s because it was: It resembled other chemical weapons attacks that have been blamed on the Syrian government over the years.

Supporters of Syrian president Bashar Al Assad quickly distanced themselves from the attack, variously claiming an air raid had hit an extremist group’s chemical weapons stockpile or that rebels had used chemical weapons to tarnish the government’s image. But the Syrian opposition and the European Union’s top diplomat, the British foreign secretary and others were quick to point the finger at Mr Al Assad’s forces.

When considering the use of chemical weapons in Syria, it is the 2013 sarin attack on Ghouta, a Damascus suburb, that usually comes to mind. It killed hundreds, risked foreign powers declaring war on the Syrian regime and led to Damascus agreeing to a US-Russian deal to hand over its chemical weapons stockpiles for destruction.

But while the Ghouta attack reaped the most victims and the most attention, chemical attacks have since continued in Syria – even after the stockpiles were supposedly destroyed. Reports of such attacks emerge frequently, albeit with lower casualty counts, and ascertaining those reports is often difficult. But the continued use of chemical weapons by the Syrian government, even after surrendering its stockpiles, has been confirmed by the United Nations and others.

Last year, UN investigators said they were convinced the Syrian government was responsible for two chlorine attacks on civilians in 2014 and 2015.

And in February, Human Rights Watch said government forces had used chlorine bombs dropped from helicopters on residential areas of Aleppo at least eight times between November 17 and December 13 last year, as regime forces were making their final push to capture the city.

For all its denials, the fact that the use of chemical weapons has continued and is documented indicates that the Assad regime feels it can get away with it.

In 2012, former US president Barack Obama warned president Assad that the use of chemical weapons in the Syrian conflict would be a “red line” that would provoke a military response. One year later, when sarin was used in Ghouta, the Obama administration considered using military action to punish the Syrian government and moved warships into the eastern Mediterranean. But with little appetite for American involvement in another war and Syria’s consent to the destruction of its chemical weapons stocks, Mr Obama backed off.

The move showed the Syrian government that no matter how loud the condemnations from the international community, nobody was going to step in. Throughout the rest of Mr Obama’s presidency, the Assad regime continued to systematically destroy hospitals and inflict bombs, execution and chemical weapons on its own people. And all Washington seemed prepared to do was issue more condemnation.

With the White House now occupied by a president with even less interest in getting embroiled in Syria’s civil war or confronting human rights abuses abroad, the Syrian government faces even less pressure to change its ways.

jwood@thenational.ae