Should Hollywood ever make a movie about the challenges of nation-building, they might well choose the story of South Sudan.

On the face of it, the birth of the landlocked African republic is the perfect David-versus-Goliath tale.

In 2011, after two decades of war against Sudanese dictator Omar Al Bashir, it at last gained independence, becoming the world’s newest state.

The country’s bid for statehood also featured a real-life cameo by George Clooney and a host of other A-list stars who led celebrity backing for the independence cause.

Sadly, the script lacks a feel-good Hollywood ending. In 2013, a falling-out between President Salva Kiir and opposition leader Riek Machar sparked a civil war between the nation’s two main ethnic groups, the Dinka and the Nuer, which has since cost nearly 400,000 lives.

With ethnic massacres, widespread rape and child soldiers roaming the battlefield, what was once a cause celebre now seems a lost cause.

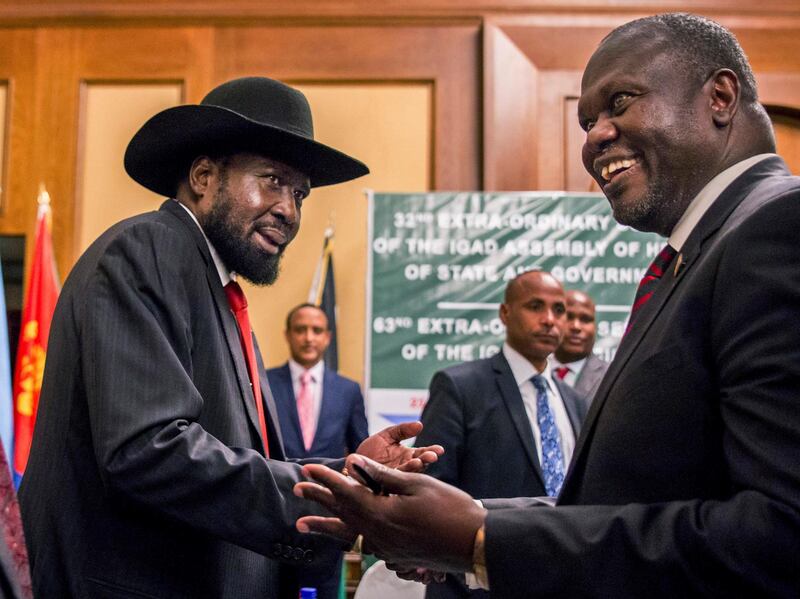

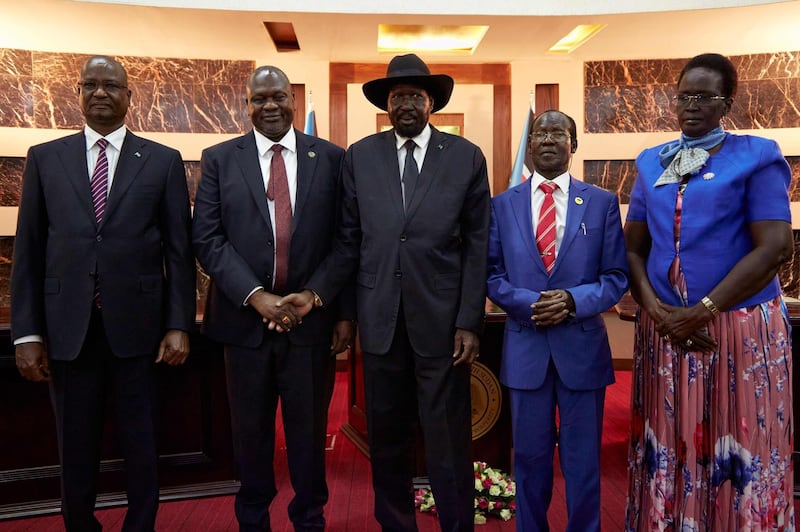

Yet with so much political, diplomatic and celebrity capital invested, the wider world has been unwilling to give up. So on February 22, after more than six years of UN-backed mediation, broken ceasefires and failed peace accords, Mr Kiir and Mr Machar signed a new power sharing agreement in the south Sudanese capital, Juba.

“We can now proclaim a new dawn,” Mr Kiir said as he shook hands with his old enemy. “Peace will never be shaken again.”

South Sudan had seen such choreographed friendliness before. Mr Machar, who previously came to blows with Mr Kiir over his “dictatorial behaviour”, signed a peace agreement to much fanfare in 2015, only for fighting to break out again the next year. He fled the country on foot, claiming his rival was trying to assassinate him.

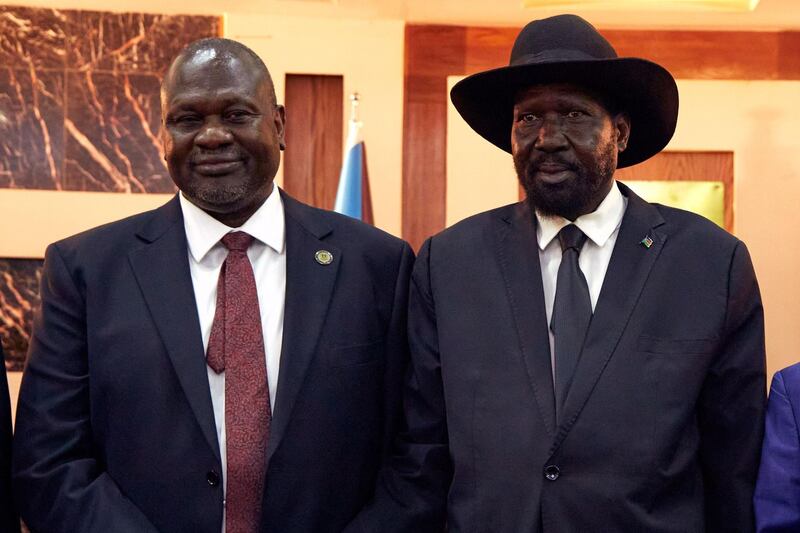

On that basis, merely getting the two men back in the same room signifies a rebuilding of trust. Until now, a key sticking point was Mr Machar’s unwillingness to take office in Juba without the protection of his own militia forces.

He has now accepted that security in the capital for him and other opposition figures will be provided by Mr Kiir – an important leap of faith. For his part, Mr Kiir has agreed to reduce the country’s 32 states to 10, a move that critics hope will prevent him gerrymandering.

But beyond last weekend’s pleasantries, immense challenges remain.

The civil conflict has reduced an already war-ravaged country to a wreck, with more than half the country’s 12 million people short of food.

Many are being starved deliberately by militias who still roam the country, while officials plunder South Sudan’s oil wealth – its only real resource.

Nor has real progress been made yet on merging government and opposition forces into a 40,000-strong unified army – a critical component of the peace deal.

“This peace deal is probably a better foundation than the one which collapsed in 2016, but may not be enough to mask the animosity,” said Ahmed Soliman, an expert with the Africa Programme at London’s Chatham House think tank.

“It’s largely about appeasing the elites that started the war in the first place, and while people will hope that they’ve seen the error of their ways, everyone is aware of the history. Integrating the military is really vital, but you are dealing with two sides that have fought each other and there are structural issues which, if not addressed, will intensify competition.”

There are further challenges, he said, in establishing courts with the power to investigate human-rights abuses – essential to any reconciliation process at community level.

Meanwhile, Mr Kiir’s pledge to reorganise state boundaries may simply displace ethnic tensions from one place to another. Against such a plethora of problems, it’s no surprise that even Mr Clooney has had his faith in South Sudan shaken.

The movie star, who puts his interest in politics partly down to having a journalist father, has made numerous visits to the region, staying in remote villages and getting to know rebel leaders.

Activists say that without Mr Clooney’s patronage – and that of fellow actor Don Cheadle – the independence cause would never have gained international backing.

Mr Clooney says he has always been “realistic” about South Sudan’s prospects, and in 2016, he launched a report accusing Mr Kiir and Mr Machar of corruptly profiteering from the civil war.

But some believe that the celebrity endorsement may ultimately have been a mixed blessing. It was easy to cast Al Bashir, who was deposed last year and was last week told he would face trial by the International Criminal Court – as a villain. But in doing so, the world overlooked the fact that Mr Kiir and Mr Machar were no angels.

“It was an unusual advocacy campaign, in that normally celebrities stick to simple humanitarian causes rather than getting involved in messy politics,” said Rob Crilly, author of Saving Darfur: Everybody’s Favourite African War.

“But it helped create this international view that the future for South Sudan lay in breaking away from the control of president Al Bashir, when it was always going to be more complicated than that.” True, it wasn’t just Hollywood that took up South Sudan’s cause.

Long before Mr Clooney’s involvement, it was adopted by US evangelical churches who saw it as a way to support Christians. The perceived treatment of southerners also struck a chord with African Americans, who took up their cause. In the end, though, too much love from the international community may have turned South Sudan’s leaders into their own worst enemies.

“It convinced South Sudan’s leaders that they’re privileged,” Mr Crilly said.

“As a result, they thought they could get away quite literally with murder.”