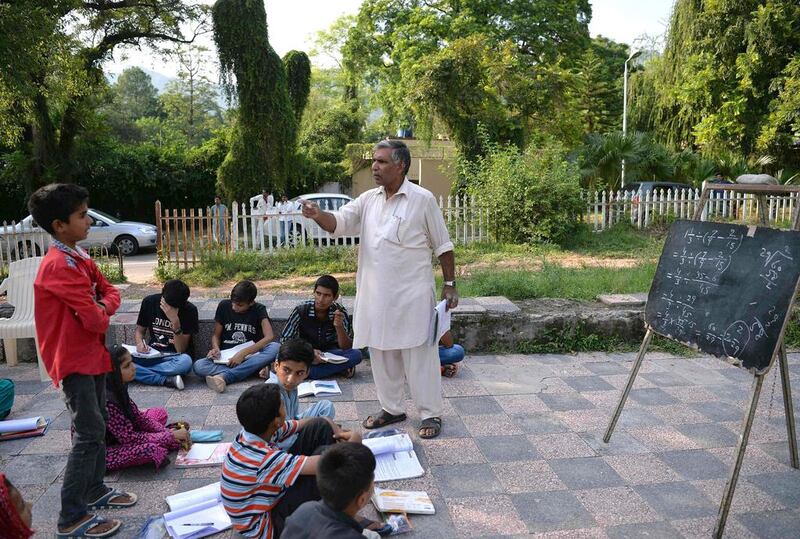

ISLAMABAD // In the corner of a pristine park in an upmarket district of Islamabad, an open-air classroom run by an ageing rescue-worker offers a beacon of hope to the city’s poorest.

For 30 years, “Master” Muhammad Ayub, whose day job with the Pakistan Civil Defence Service includes defusing bombs and putting out fires, has cycled from his office to the makeshift school to teach children from surrounding slums for free.

There are no walls, no roof and no chairs — and students dutifully rise to move en masse as the sun makes its way across the sky — it is their only source of lighting so they must follow it.

In a country where education is underfunded and 24 million children are not in school, grey-haired Ayub, 58, is hailed as a hero for providing his charges with hope for a better future.

“I was rescued from the darkness of illiteracy by an angel in the shape of Master Ayub when I was nine and collecting firewood,” said Farhat Abbas, now 20. He is now Master Ayub’s teaching assistant, as well as studying for a bachelor’s degree at a local university.

The school has rescued many others like Mr Abbas. Some have gone on to jobs in government and businesses that would have otherwise have been beyond their reach.

Master Ayub started his school in 1986 when he moved to the recently-built capital from the sleepy agricultural town of Mandi Bahauddin. With its wide boulevards, stunning views of the Margalla hills and impressive monuments, Islamabad was a world away from the young man’s hometown.

But, he recalls, “When I arrived, I was puzzled to see small children working in the streets, begging or cleaning cars or selling flowers and I wondered, how come they have to do this in a posh capital city?”

One day he came across a boy washing cars in the market place and asked him why he wasn’t in school.

“I asked him if he wanted to study and he said ‘yes’. Right there I gave him a notebook, a book, a pencil and a rubber and started teaching him,” said Master Ayub, himself a high school graduate who left college before finishing his degree.

“The next day the boy brought another with him, and within a week there were 50 children in my class.”

He began by teaching them in a corner of the marketplace, but the shopkeepers shooed him away. He then set up outside a government school but was told to pack up after influential people living nearby complained the children were causing a nuisance. Finally he shifted to the park, which adjoins some of the most expensive houses in the city — but is also near a slum full of minority Christian families.

Founded in 1960, Islamabad ith little public housing for the poor, who work in menial jobs and as domestic servants for the wealthy. Consequently, numerous slums sprang up throughout the city, but because their homes are not legally recognised, it is often hard to enrol slum children in registered schools.

Hina Shahbaz, 17, moved with her parents to Islamabad two years ago, but lacked the paperwork to get into a school. She started attending Master Ayub’s classes, while he used his contacts among local officials built up over the years to get her enrolled at a formal school.

She continues to help out by teaching younger students, while receiving maths tuition from her old teacher. “I like science and I want to become an engineer,” she said.

The early years were hard, says Master Ayub. The authorities suspected he was a missionary because he was teaching so many Christians (he is in fact a Muslim). But suspicion fell away when he received an award from the ministry of education in 2012 and a presidential award last year.

Master Ayub isn’t in it for the accolades, however. “I started this work because if these children do not get education, they will fall into wrong hands, become criminals or terrorists. I want them to get education and join the police, the army, become doctors and engineers.”

As he approaches 60, he says it is time to build his legacy — literally. “I have bought some space here and built two rooms because I want to teach computer systems.I want to leave a facility behind after my death where these children continue to get the light of education.”

* Agence France-Presse