LONDON // The word reformer is often used to describe the late King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia, and there is little doubt that the country has changed in the 10 years since he formally inherited the throne from his brother, King Fahd.

In reality, King Abdullah had been pulling the strings for a decade when he was crowned in 2005, ever since King Fahd suffered a debilitating stroke in 1995. But it was the mid-2000s when King Abdullah’s reforms began to take shape.

Under his stewardship the Saudi economy grew five-fold. It expanded to US$772.610bn in 2014 from US$157.7 billion in 1996, according to the International Monetary Fund and World Bank.

Massive infrastructure projects were launched as a boom in development swept the Arabian Gulf, with Saudi Arabia setting up a series of economic cities — including the King Abdullah Financial District near Riyadh — and inviting international construction firms and architects to build Dubai and Abu Dhabi-esque skyscrapers.

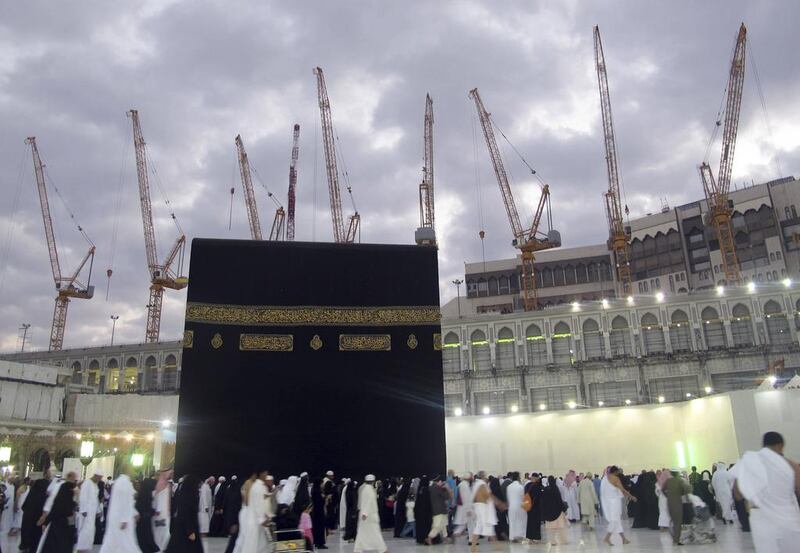

Meanwhile in Mecca, huge construction projects saw the expansion of the Grand Mosque and other infrastructure initiatives such as railways and improvements to roads and access for the millions of pilgrims visiting the holy city every year. The Mecca Clock Tower, which looms over the mosque, was completed in 2010.

The construction boom came at the same time as a limited opening of the Saudi stock exchange, the Tadawul, with foreign investors permitted to buy shares via credit default swaps in massive Saudi firms such as Saudi Arabia Basic Industries Corporation and talk that direct investment may follow.

King Abdullah also pioneered investment in education, and the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology was said to be his pet project, and not just in name. The university allowed male and female students to mix for the first time and was an effort to put the kingdom on the map for more than just oil, pioneering research into sustainable development and renewable energy.

All this notwithstanding, Saudi Arabia remained very much an oil story, with critics pointing out that every new initiative pushed by King Abdullah was reliant on Saudi Arabia’s massive oil reserves. That was fine when prices were high, but as oil began to slide at the end of last year, things started to look far more uncertain for the Saudis.

Analysts warned that falling oil prices endangered almost every aspect of the Saudi economy — from its stock exchange (where petrochemicals have a 40 per cent weighting) to construction, almost all of which was paid for by oil revenues. They have taken comfort from the fact that King Abdullah’s oil minister Ali Al Naimi will remain under his successor and half-brother King Salman bin Abdulaziz, as the 79-year-old is considered a safe pair of hands.

“The oil ministry is largely headed by technocrats and so it is relatively shielded from changes in the kingdom’s political environment. We suspect that Al Naimi will continue to take a sanguine view of the fall in oil prices and will resist pressure from other Opec members to cut oil output in order to shore up prices,” said Jason Tuvey, Middle East economist at Capital Economics in London.

But oil prices alone cannot be blamed for the stalling of the Saudi openness drive that came in 2012 and 2013, and the failure of many of Abdullah’s reforms.

While he may have wanted to be remembered for increasing access to housing for young Saudis, in 2015 the millions of new homes he promised four years before were still not built and the much-lauded mortgage law remained bound in legal hurdles.

Meanwhile, rules were introduced forcing companies in the kingdom to hire Saudi nationals or face large fines. Indeed, critics said that while the Saudi Arabian General Investment Authority talked a good game on encouraging international investors, it had become unpredictable in licensing foreign companies using selective and unclear criteria.

“As a result, it has become a more difficult place to work and invest in. These difficulties have been compounded by changes in the labour laws,” said Imad Ghandour, managing director at CedarBridge Partners, which has offices in Saudi Arabia, Egypt and the UAE.

In short, King Abdullah was undoubtedly a reformer — but a cautious one.

“He acknowledged the need for Saudi Arabia to diversify away from oil and for the economy to open up to the world. He put a lot of effort into improving the education system and, more recently, to attract investment from abroad in order to create more jobs in the private sector. But his reforms were, on the whole, relatively slow-going,” said Mr Tuvey.

foreign.desk@thenational.ae