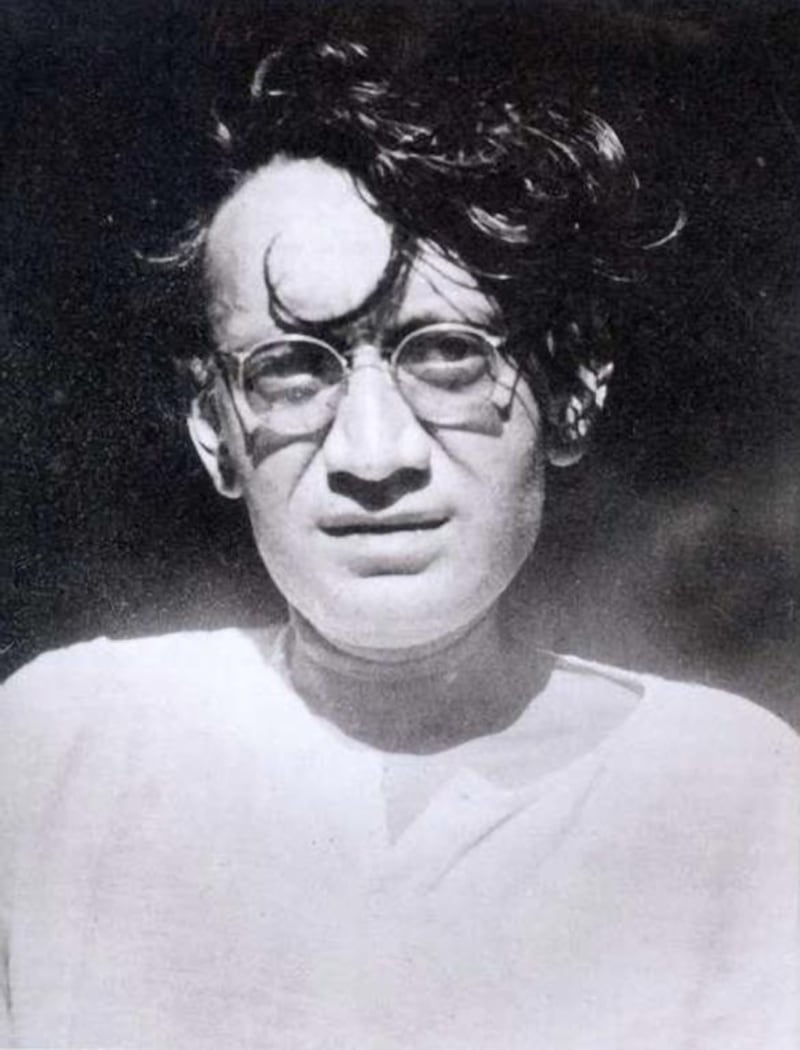

NEW DELHI // For nearly a decade now, Abhinay Banker, an Ahmedabad-based theatre director, has staged dramatisations of the short stories of the Urdu writer Saadat Hassan Manto.

Over most of that period, Mr Banker estimated, only a fifth of his audience knew about Manto or his work at all.

“But of late, I find, that has begun to change,” Mr Banker said. “People come to find me backstage now, telling me that they’ve read something about Manto or that they recognised what they were watching.”

Manto died in 1955, but within the repertory of Indian theatre — particularly in Mumbai — and within the world of Urdu letters, his acid, cynical fiction has been kept alive.

Naseeruddin Shah, one of India’s most famous actors, has staged many adaptations of stories such as “Bu,” in which a man recalls the particular odour of a woman he had known decades earlier.

“What’s happening now is, outside of these theatrical circles, people who don’t read or know Urdu are also becoming aware about his writing,” Mr Banker said.

Manto’s birth centenary was commemorated in 2012, and the subsequent years since have seen a flurry of new translations of his work into English and a spate of literary criticism surrounding it.

In Pakistan, a new biographical television serial titled “Main Manto” (or “I, Manto”) is in development.

It is only the English-speaking world that is discovering Manto, most of his translators are quick to point out.

The journalist Aakar Patel, who has just released “Why I Write” an English translation of Manto’s essays, said: “He was pretty obscure till the 1980s. His daughter Nighat Patel told me she had no idea, growing up, what a big writer her father was.”

Manto was born in the British Punjab in 1912 and died in Lahore, in Pakistan, but some of his best work came during his stay in Mumbai

(formerly Bombay), between 1936 and 1948. Here he worked in the film industry, writing scripts, magazine articles and short stories.

His non-fiction sketches dealt lightly with everyday life: “people who bummed cigarettes, on the debate over Hindi and Urdu, on potholes, on the mindlessness of Indian ways,” Mr Patel said. Manto’s fiction was dark and funny, and he revelled in writing about the seamier side of Mumbai life; over the course of his career, he was tried for obscenity six times.

“In the South Asia of half a century ago, he’d just have been dismissed as a reprobate by even his fellow writers,” Chandrahas Choudhury, a New Delhi-based literary critic, said. “While today, young people can read him and see that to see life clearly, first one has to blow away the fog of a hundred moralistic assumptions.”

When the subcontinent was divided into India and Pakistan in 1947, Manto wrote vividly about the pain and violence of that partition. Perhaps his best known story, “Toba Tek Singh” revolves around a Sikh inmate of a psychiatric asylum who was torn between India and Pakistan.

Manto moved to Pakistan in early 1948, and his observations about that newborn state resonate particularly strongly today.

“In the last few years, for Pakistanis, Manto has become prophetic,” Mr Patel said. “He traced the trajectory the Islamic state would take more accurately than [the poet Muhammad] Iqbal and [the politician Mohammad Ali] Jinnah, its two proponents. That makes him not just relevant but indispensable.”

Aatish Taseer, a New Delhi-based novelist who translated a selection of Manto’s short fiction in 2008, is not fond of the partition stories. “I found them too pat, full of false equivalences,” Mr Taseer said.

But he was drawn to Manto’s range. “I was dazzled by him,” Mr Taseer said. Apart from the partition stories, “I loved the rest: the stories about cinema, about prostitutes, about the independence movement, the careful observation of certain street types, a feeling for economy.”

Manto has been particularly interesting to him, and to others of India’s English-speaking world, Mr Taseer said, because of “how culturally arid the English world can feel in India. There is so little writing in which we get that sense, as we do with Manto, of a writer deeply immersed in his material, writing out of his material, as it were.”

Some say Manto’s translators have not always served him well. Matt Reeck, an American writer who was studying Urdu in Lucknow some years ago, read Manto first in the original Urdu and then in translation.

“I felt I could translate the dialogue better and in general render translations that would better capture the stories’ youthful, vital energy,” Mr Reeck, who lives in New York, said. “Also, almost all of the translations that had been done hadn’t been edited so as to provide one perspective on his work.”

Mr Reeck latched on to Manto’s love for Mumbai, collecting his best stories about that city. “Bombay Stories” was published in India in 2012.

Mr Choudhury noted that Manto’s works spoke particularly to the younger readers in India and Pakistan. Manto wrote bluntly of his

distaste for religious zealotry, sympathy to prostitutes, and earnestly about personal freedom. “To strive for freedom is fine. I can even understand dying for it,” Mmanto wrote in one essay.

“I think two wonderful things about people of our generation are that we are sceptical of the grand theories of nationalism and religion, and much more clear-eyed about sex and freedom,” Mr Choudhury said. “Manto speaks to all these things.”

ssubramanian@thenational.ae