It is 50 years since Israel launched a pre-emptive military strike on Egypt and began a war that changed the face of the Middle East. This is the first story in a four-part series on the 1967 Arab-Israeli war – the refugees it created, the families it destroyed, the legacy of mistrust it left behind.

JERUSALEM // With a window that faces onto the Muslim shrine the Dome of the Rock and the Western Wall Jewish holy site, Mohammed Abed Al Jalel Abed Al Maloudi has one of the most enviable views in Jerusalem’s Old City. But to the 78-year-old Palestinian, it is a panorama of loss.

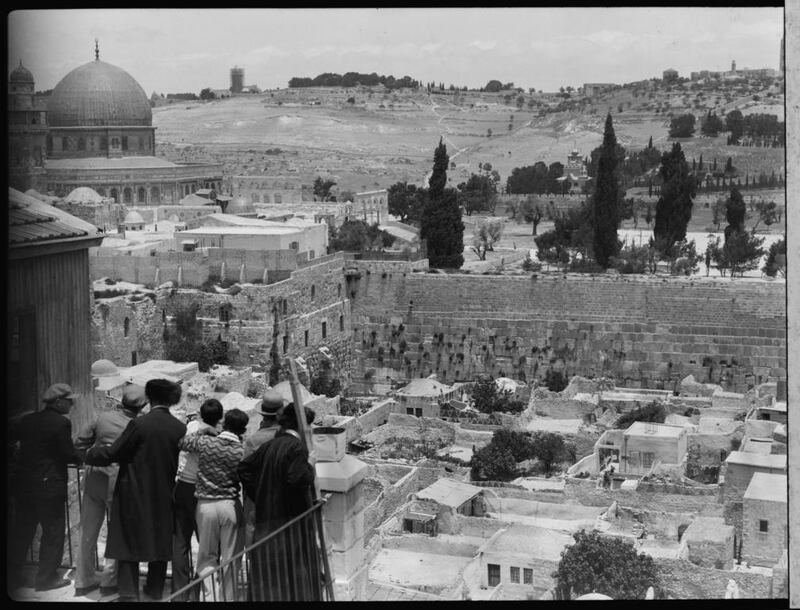

Mr Al Maloudi grew up in the Moroccan Quarter, a small neighbourhood that abutted the Western Wall until Israel bulldozed it to build a prayer pavilion there 50 years ago. When Mr Al Maloudi looks out his window onto the sand-coloured stone terrace filled with Jewish worshippers and tourists, he sees his childhood home and the alley where he used to play with his friends, tossing a ball made with his mother’s sock.

This week, Israel marks the 50th anniversary of its victory against three Arab armies over six days in the 1967 Arab-Israeli war. The war placed the Western Wall, the second most sacred site in Judaism, into Jewish hands for the first time in 2,000 years. But one people’s spiritual homecoming lead to another’s dispossession.

Today, there is no sign at the Western Wall pavilion recognising the neighbourhood that existed there a half century before. The Moroccan Quarter is a historical footnote, largely forgotten by the world and remembered by Palestinians as one in a string of countless tragedies. But the eviction remains firmly in the memories of the surviving Moroccan Quarter residents, who have passed the story of the place onto their children and grandchildren, some of whom dream of reconstituting the old neighbourhood in a new location.

On June 7, 1967, Israeli forces captured the Old City from Jordan and “liberated” the Western Wall in Israeli parlance. Israeli paratroopers wept in front of the ancient stones, believing that the next chapter of Jewish history was being written before their eyes. Photographer David Rubinger snapped a portrait of three paratroopers gazing in reverence next to the wall, now the most iconic image from that war.

Jerusalem authorities knew they had to act quickly to accommodate Jewish demand to visit the holy site, but it remains unclear exactly who ordered the destruction of the Moroccan Quarter. "There were no formal decisions, no written approvals and no explicit decision making," wrote Israeli reporter Uzi Benziman in a recent account in Israel's Haaretz magazine. To avoid the appearance of government responsibility, then-Jerusalem mayor, Teddy Kollek, enlisted a group of Jerusalem contractors to carry out the deed.

According to an article by the academic Thomas Abowd, published in the Jerusalem Quarterly journal in 2000, residents were given just two hours' warning to leave their homes. Fifteen contractors arrived at the Western Wall in darkness on June 10, the last day of the war, with bulldozers and other equipment in tow, wrote Israeli historian Tom Segev in his book, 1967. Their first victims were two public toilets at the Western Wall, followed by the 135 houses. One elderly woman was trapped in the refuse of her own home. She made it out, but died shortly after – the one life claimed in the clearance. The rush to demolish created a chaotic scene; people wailed watching their homes reduced to rubble. Palestinian historian Salim Tamari described the haste as "pre-emptive". The Israelis "didn't want people to organise themselves or go to court" to halt the evacuation, he said.

Many of the families went back to Morocco with the help of the then-Moroccan king, Hassan II, wrote Mr Abowd, now a lecturer at Tufts University in Massachusetts. Others were scattered across Jerusalem, with a large number finding homes in the Shuafat Refugee Camp. Israel compensated families with 200 Jordanian dinars each, but about half refused to take it in protest, the community’s head, known as a mukhtar, told Mr Abowd.

Meron Benvenisti, an Israeli administrator to East Jerusalem who later served as Mr Kollek's deputy mayor, was part of the decision to destroy the Moroccan Quarter. He witnessed the demolition first-hand. "It was inevitable, absolutely inevitable," he told The National, sitting on a brown couch in his apartment in an assisted living facility outside of Jerusalem. "If you have war, people die and houses are destroyed."

Mr Benvenisti said the Moroccan Quarter residents were “victims, no question about it”. But he warned against decontextualising the demolition; for years, Jewish visitors to the site had been harassed by Palestinians, he said. Tensions there boiled over in 1929 in an Arab uprising that killed 133 Jews across British Mandate Palestine. Another 110 Arabs were killed, most by British forces seeking to suppress the revolt. When the wall came under Jewish control in 1967, “it was an outburst of messianic proportions”, he said. “There was no way that the Jewish people could have expressed their feelings towards the Western Wall” if the neighbourhood had stayed put.

But for Mr Al Maloudi, who keeps a black and white photograph of the Moroccan Quarter at his bedside, there is no understanding the demolition, only condemning it. “They destroyed a future of a people,” he said.

While Mr Al Maloudi now lives just off the well-marked path to the Western Wall, other Moroccan Quarter residents are cut off from the area they once called home. Mahmoud Al Mahdi, 73, lives on a rocky hillside in Abu Dis, a Jerusalem suburb separated from the holy city by Israel’s concrete security barrier. In front of his three-story stone home is a small orchard, where Mr Al Mahdi grows grapes, apples, pomegranates, peaches and olives. A Palestinian flag flaps in the breeze.

He has not been to Jerusalem since 2014 or 2015 – he can’t remember which – when he was granted a rare permit to enter for Ramadan, but even then he said he was not allowed to visit the Western Wall. Mr Al Mahdi was once an active member of the Palestine Liberation Organisation, and though he is now retired Israel will not let him enter the holy city, he said.

Even so, Mr Al Mahdi vividly remembers the Moroccan Quarter. Sitting in his living room, where a wide screen television broadcasts interviews with nervous parents about the upcoming Palestinian school exams, he takes out a white piece of paper and a blue pen and traces the contours of the disappeared neighbourhood. He draws a long blue line, the Western Wall, and a star, his childhood home.

Mr Al Mahdi’s father came to Jerusalem from Morocco in the 1930s, at the end of his Haj pilgrimage to Mecca. By then, the neighbourhood was well established as a landing pad for Muslims from the Maghreb. Several Islamic trusts enabled Muslim families to live in the Moroccan Quarter and work at the Haram Al Sharif, the esplanade on which sits Al Aqsa Mosque, the third holiest site in Sunni Islam. By 1967, there were approximately 650 people living there, according to Mr Abowd’s research.

__________________________________

50 years of Israeli occupation

■ A Jerusalem street that bridges and divides

■ Editorial: Five decades of occupation

■ Comment: The 1967 war and the injustices that persist

■ Pictures: Remembering the demolition of Jerusalem's Moroccan Quarter

__________________________________

For Mr Al Mahdi, living in view of the Western Wall was a special part of growing up. The wall, sacred to Jews as a remnant of the retaining wall of the Second Jewish Temple, which was destroyed by the Romans in 70AD, is also a religious place for Muslims. They refer to it as the Buraq Wall, where the Prophet Mohammed hitched his white steed, or the Buraq, before riding it into heaven on his night journey.

Mr Al Mahdi learnt the ancient history of the stone wall, how it was built by Herod the Great, by reading tourist brochures handed out at the site. Though Jordan prohibited Israeli Jews from going there between 1948 and 1967, Mr Al Mahdi said he sometimes spotted Jewish worshippers at the wall, mixed in with the tourists. He recognised them by the way they lingered at the stones, sometimes weeping in mourning over the destroyed ancient temple.

Today, Mr Al Mahdi is unable to reconcile the fact that his family home was destroyed to accommodate Jewish prayer. He was away at university in Baghdad during the war. When he reunited with his parents, they told him that they woke up on the night of the demolition to the sound of bulldozers crushing their neighbours’ homes.

“It is inhumane, and it doesn’t make sense at all,” he said.

In late May, a group of about 40 descendants of the Moroccan Quarter families, as well as a few of the original inhabitants, gathered over soda and chocolate bars at a Jerusalem sports centre not far from the Western Wall. The group has convened on and off for years in an effort to keep the community alive, but the May meeting had a special urgency because the community’s mukhtar had recently passed away. It was an opportunity to refocus its mission, which might at some point include building the Moroccan Quarter anew at a different site, said organiser Hamzeh Mughrabi.

After socialising for a few minutes, the participants, all men, filed into a meeting hall hung with a large sign bearing the Libyan, Moroccan, Tunisian and Algerian flags for a series of speeches and a Quran reading. One elder at the podium said he had not seen such a gathering since 1967.

In the audience was a slim 30-year-old named Ali Omar Mughrabi. His grandmother, Zulfa Omar Mughrabi, 77, still remembers the demolition of the Moroccan Quarter, how, in the rush to evacuate, she left behind her daughter, just over a month old. Israelis saw the baby through the window, and mistook her tiny body, covered in dust, for a grenade. Ms Omar Mughrabi spoke no Hebrew, but a friend interceded on her behalf and she was allowed back into her home. She quickly unwrapped her daughter to prove she was not a weapon, and then continued her flight. She said that her family was the last to leave the Moroccan Quarter. Later, she sold her gold jewellery to feed her children. Mr Omar Mughrabi grew up on such tales of the evacuation, but he always felt disconnected from the community that his grandparents left behind. In the group, he sees a chance to reconnect with the men who might have been his neighbours had his family been allowed to stay in the Moroccan Quarter.

“I wanted to know my family,” he said.

While Ms Omar Mughrabi never returned to the site, her grandson visited the Western Wall five years ago, though not by choice. Mr Omar Mughrabi had been arrested for driving without a licence, and he was placed in a community service programme in lieu of serving jail time. Part of the programme was a tour of the Western Wall, which the Israeli guide described as a holy place “for the Jews”, he recalled. Mr Omar Mughrabi did not want to get in trouble, but he could not let the comment pass unanswered. He registered a small complaint against the tide of history.

“I said, ‘No, this is our holy place, where we used to live.”

foreign.desk@thenational.ae