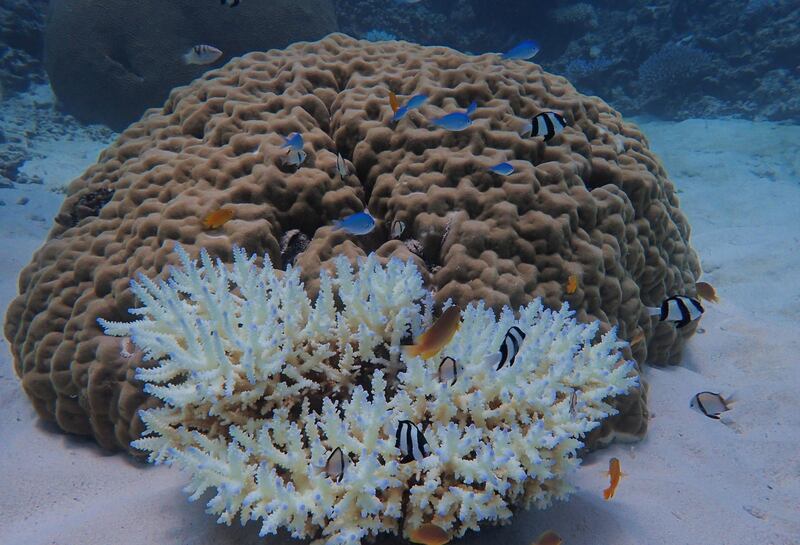

An aerial survey of the Great Barrier Reef shows coral bleaching is sweeping across the area off the east of Australia for the third time in five years.

Bleaching has struck all three regions of the world's largest coral reef system and is more widespread than ever, scientists from James Cook University in Queensland said on Tuesday.

The air surveys of 1,036 reefs in the past two weeks found bleached coral in the northern, central and southern areas, James Cook University's Prof Terry Hughes said.

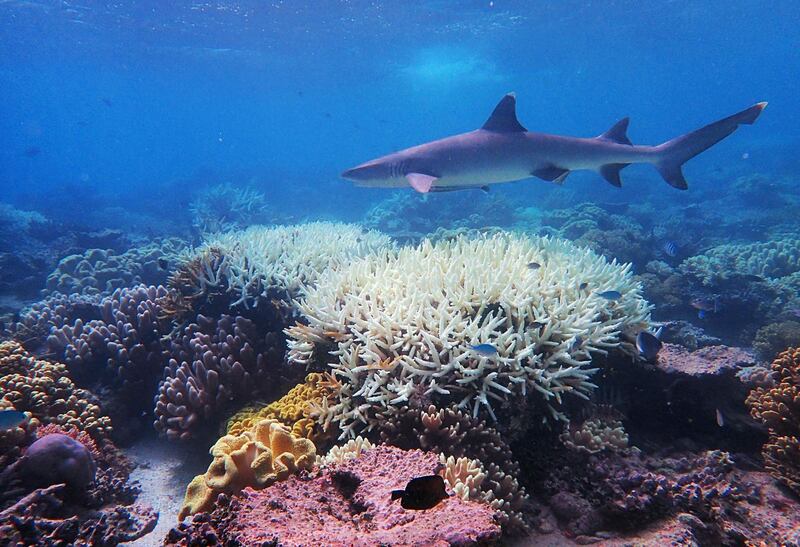

“As summers grow hotter and hotter, we no longer need an El Nino event to trigger mass bleaching at the scale of the Great Barrier Reef,” Prof Hughes said. “Of the five events we have seen so far, only 1998 and 2016 occurred during El Nino conditions.”

El Nino is a climate pattern that starts with a band of warm ocean water in the central and east-central Pacific around the equator and affects global weather.

The Great Barrier Reef is made up of 2,900 separate reefs and 900 islands. It is unable to recover because there is not enough time between bleaching events.

“We have already seen the first example of back-to-back bleaching — in the consecutive summers of 2016 and 2017,” Mr Hughes said.

The number of reefs spared from bleaching is shrinking as it becomes more widespread.

He said underwater surveys will be carried out later in the year to assess the extent of the damage.

In early March, David Wachenfeld, chief scientist at the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, said the reef was facing a critical period of heat stress over the coming weeks after the most widespread coral bleaching the natural wonder has ever endured.

The authority, the government agency that manages the coral expanse off northeast Australia, said ocean temperatures over the next month would be crucial to how the reef recovers from heat-induced bleaching.

“The forecasts … indicate that we can expect ongoing levels of thermal stress for at least the next two weeks and maybe three or four weeks,” Mr Wachenfeld said in a weekly update on the reef’s health.

“So this still is a critical time for the reef and it is the weather conditions over the next two to four weeks that will determine the final outcome.”

Ocean temperatures across most of the reef were 0.5°C to 1.5°C above the March average.

In parts of the marine park in the south that avoided the ravages of previous bleachings, ocean temperatures were 2°C to 3°C above average.

The authority had received 250 reports of sightings of bleached coral because of elevated ocean temperatures during an unusually hot February.

The 345,400-square-kilometre coral network has been devastated by four coral bleaching events since 1998. The most deadly were the most recent, in the summers of 2016 and 2017.