An unmanned Nasa spacecraft sent a signal back to Earth on Tuesday that it successfully made it through a risky fly-by past the most distant planetary object studied, the US space agency said.

"We have a healthy spacecraft," said Alice Bowman, missions operations manager for the New Horizons spacecraft, which zipped by Ultima Thule at 12.33am (09.33 UAE time) on New Year's Day.

"We have just accomplished the most distant fly-by," she said.

The "phone home" signals took about 10 hours to reach Earth following the fly-by, which took place 6.4 billion kilometres away.

Images and data were to start arriving later on Tuesday, "science to help us understand the origins of our solar system", Ms Bowman said.

The New Horizons probe was scheduled to reach the "third zone" in the uncharted heart of the Kuiper Belt at about 9am US time. Scientists will not have confirmation of its successful arrival until the probe communicates its whereabouts through Nasa's Deep Space Network at 7pm, about 10 hours later.

Once it enters the peripheral layer of the belt, containing icy bodies and leftover fragments from the solar system's creation, the probe will get its first close-up look of Ultima Thule, a cool mass shaped like a giant peanut, using seven onboard instruments.

Scientists had not discovered Ultima Thule when the probe was launched, according to Nasa, making the mission unique in that respect. In 2014, astronomers found Thule using the Hubble Space Telescope and selected it for New Horizon's extended mission in 2015.

"Anything's possible out there in this very unknown region," John Spencer, deputy project scientist for New Horizons, said on Monday at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland.

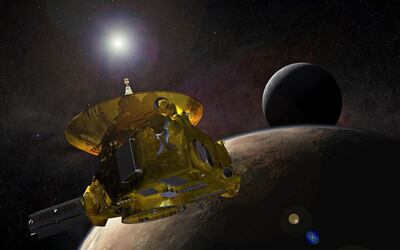

Launched in January 2006, New Horizons embarked on a 4 billion mile journey towards the solar system's frigid edge to study the dwarf planet Pluto and its five moons.

During a 2015 fly-by, the probe found Pluto to be slightly larger than previously thought. In March, it revealed that methane-rich dunes were on the icy dwarf planet's surface.

After trekking 1 billion miles beyond Pluto into the Kuiper Belt, New Horizons will now seek clues about the formation of the solar system and its planets.

As the probe flies 3,500km above Thule's surface, scientists hope it will detect the chemical composition of its atmosphere and terrain in what Nasa says will be the closest observation of a body so remote.

"We are straining the capabilities of this spacecraft, and by tomorrow we'll know how we did," New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern said during a news conference at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. "There are no second chances for New Horizons."

While the mission marks the farthest close encounter of an object within our solar system, Nasa's Voyager 1 and 2, a pair of deep space probes launched in 1977, have reached greater distances on a mission to survey extrasolar bodies - the first being about 13.5 billion miles from Earth and the second being more than 17.8 billion kilometres. Both probes are still in operation.

________________

Read more from space:

Scientists aim to dim the sun to tackle climate change

The ageing 1977 space probe Voyager 2 leaves the heliosphere and enters 'the space between'