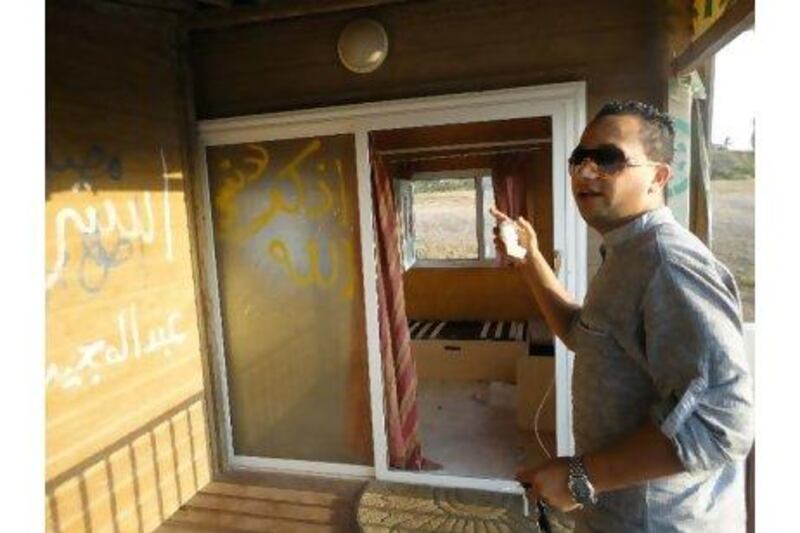

TRIPOLI // The metal gate of one of Safia Qaddafi's beachfront getaways in Tripoli has been busted open and children run through the ransacked bungalows and frolic in the ocean.

"Before, only Qaddafi's family could come here," said Alaa Murad, a 24-year-old Libyan-Canadian business student whose great-grandfather had owned the land before it was requisitioned for "army use" in 1972 by Colonel Muammar Qaddafi's regime. Instead, it was given eight years later to Col Qaddafi's second wife, Safia, who built small cabins and the kind of large tented area her husband seemed to love.

But on this sunset visit to the 5-square-kilometre site, Mr Murad was not depressed. The beautiful view and prime location appear to be perfect for a new hotel.

"My father and I will get this land back," he said. "Then we can build a new hotel. Things are going to get good in Libya."

Col Qaddafi refused to allow development along Tripoli's coast, except for a group of modern hotels and buildings under the control of his sons and close aides. Tourism was to become a new sector of the economy, but only to be exploited by his sons and senior regime loyalists.

It was the same throughout the economy, Libyan businessmen say. Under the guise of an increasingly liberal economy, the regime controlled everything from how much money someone could earn to whether they could get a shipment from abroad - and how big a bribe they would have to pay in order to stay in business.

"Now we can try capitalism," said one senior official at the new Libyan Central Bank, seeing one businessman after another while his Turkish coffee went cold. "Before we did not have this."

While Egypt and Tunisia face a much greater challenge in reforming their economies and meeting the demands for social justice from their burgeoning populations, Libya is seen as having a brighter economic future. It has as much as $170 billion (Dh624.3bn) in assets (though much of it is still frozen overseas under orders of a United Nations resolution), a huge supply of oil and a population of just six million.

Yesterday, the British prime minister, David Cameron, and the French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, during a visit to Tripoli, promised to release billions of dollars of those frozen assets, the Associated Press reported.

A spokeswoman for Mr Cameron spokeswoman said a new United Nations Security Council resolution authorising the release of all frozen Libyan assets has support of all five permanent members.

Britain has also won approval from the UN sanctions committee on Libya to release a further $950 million immediately to fund public-sector salaries, she said. Britain will also offer funds for weapons decommissioning, mine clearance, medical assistance for those with grave combat injuries and specialist help in locating and secure chemical weapons.

The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) formally recognised Libya this week, which should usher in teams of economic strategists to help the new government get the country back on track.

IMF chief Christine Lagarde said: "The fund stands ready to help the authorities through technical assistance, policy advice, and financial support if requested, as they begin to rebuild Libya's economy," according to the Agence France-Presse.

Corruption will be one of the biggest issues to tackle. Improving government salaries will be an early priority to avoid situations where officials are tempted by wealth much greater than their salaries.

Bassam Ghellal, a founder of Whispering Bell, a security risk management company based in Dubai, said: "On every single level, there was corruption. There were these officials earning $300 a month, but they had a lot of power. It was inevitable."

For years, Ghanem Bashir's uncle had a warning for him: always tuck away 30 per cent of your profits for bribes. While Mr Bashir says his uncle was not corrupt, he understood the Qaddafi regime better than most. He had been one of the small group with the colonel when he took over the country in a military coup.

"During the last six months, we spent everything we had to stop Qaddafi," said Mr Bashir, who is the proprietor of 11 clothing stores and the head of the Libyan Businessmen's Charity Club in the eastern city of Benghazi. "Now, I hope, we can spend on growing our businesses."

The club Mr Bashir helped found has played an outsize role in the revolution. Their first contributions paid for a mobile field hospital to be sent to the frontlines, as well as clothing, food and medical supplies. They have put up almost $2 million as a reward for the capture of Col Qaddafi so that "he has no place to hide and there is a fear of even his closest officers", Mr Bashir said.

Lately, the businessmen have paid for 100,000 school bags for children to restart classes in the coming weeks. The group also built a Museum of the Crimes of Qaddafi in an old Italian-era building on the corniche of Benghazi. Another group of businessmen in Misurata, the hardest hit city during the uprising, bought weapons and paid for aircraft to airlift the injured.

Mr Bashir said he participated in the revolution in another key way. An electrical engineer by training, he helped the first rebel groups to remove rocket launchers meant for fighter jets and weld them to trucks.

"We figured out you only needed a small battery to launch these rockets," he said. "We tested it out in Tobruk. Then they brought them to the front lines. They weren't very accurate but they scared Qaddafi's troops."