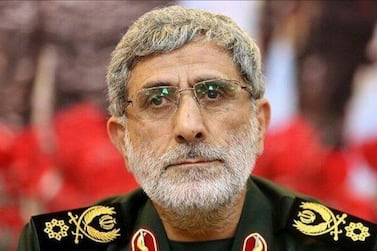

To understand Esmail Qaani, who replaced Qasem Suleimani as the commander of Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guards Quds Force, you must look at his two decades of work in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

He might be unknown in the region to the West of the country, but his eastern neighbours know him well, from Kabul and Islamabad, to Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and even in India, a country that worked with him to support the overthrow of Afghanistan's Taliban government in the 1990s.

Mr Qaani is media-shy and less bombastic than his predecessor, but no less lethal. After the September 11, 2001, attacks in the US, his proxies on the ground co-operated with US military to help secure Afghanistan, exploiting a downturn in US relations with Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Pakistan, and other Cold War allies.

Tackling a nuclear-armed Pakistan without provoking a full-frontal confrontation might be one of Mr Qaani’s enduring legacies. He created an impeccable spy and terrorism network that operated inside Pakistan for more than a decade until 2015, destabilising the Balochistan and the Pakistani business hub city of Karachi. He orchestrated spectacular attacks that were meant to scuttle the ambitious joint China-Pakistan economic corridor linking western China to Pakistan’s Gwadar port on the Arabian Sea.

Mr Qaani used his Pakistan links to raise the Zeynabiyoun militia, which started as a formidable sectarian brigade of Pakistani volunteers to fight in Syria, until it was busted by Islamabad. These cells preyed on poor Pakistanis from the Shia minority, deploying their religious fervour to fight Iran’s wars.

Adding to Pakistan’s woes, the IRGC and Quds Force often used Pakistani citizens or stolen passports for terrorism and espionage. For example, in March 2017, Pakistani Syed Mustufa Haidar Naqvi was jailed in Germany for spying on Israeli interests. German investigators proved he worked for the Quds Force, and was recruited when he came to Germany in 2012 to study.

Another example is an assassination attempt in 1985 on the now late Emir of Kuwait, Sheikh Jaber Al Ahmed Al Jaber Al Sabah. The two Iranians involved in the attack carried Pakistani passports. It had been planned and executed by Abu Mehdi Al Muhandis, an Iraqi militia commander who was killed in the same drone attack that killed Suleimani on January 3.

In Pakistan and Afghanistan, Mr Qaani’s job description was simple: stop a possible ground invasion of Iran from Afghanistan or Pakistani and end landlocked Afghanistan’s dependence on Pakistani ports.

This area has one of the world’s most dangerous border zones: the badlands where Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan meet, which is infested with crime syndicates, human traffickers, extremist and separatist groups, and covert operators. The IRGC believe that if there were to be a US invasion, it would happen from here.

This is where the Iranian population is ethnically non-Persian, it is Sunni majority and the Iranian supreme leader is not popular there, with violent indigenous resistance to Tehran prevalent. It is the ideal environment to tempt covert foreign meddling and no amount of assurances from Kabul or Islamabad have assuaged Iran's leaders.

Mr Qaani engaged the US and allies Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and other Arab states in an excruciating, five-year war of attrition in Afghanistan, prolonging the civil war in the 1990s. The Taliban seized Kabul in 1996, backed by Pakistan with tacit support from regional and international allies, and one year later Mr Qaani, under the guidance of Suleimani, put together a guerrilla alliance to challenge efforts to form an Afghan government.

While Suleimani focused on precipitating the collapse of Arab states, he had little appetite for work on Iran’s eastern border. But with Mr Qaani expertise in both the east and the Middle East, there is little room for optimism that Iran’s long-standing policy of region wide meddling will change.