Drafting the country's constitution is a delicate balancing act between the historically abused power of the president and a new parliament determined to rein in the head of state. Bradley Hope, foreign correspondent, reports

CAIRO // Nearly a year after Hosni Mubarak was toppled, the argument still rages in the coffee houses and homes of Cairo over whether the uprising that forced him from office was a revolution.

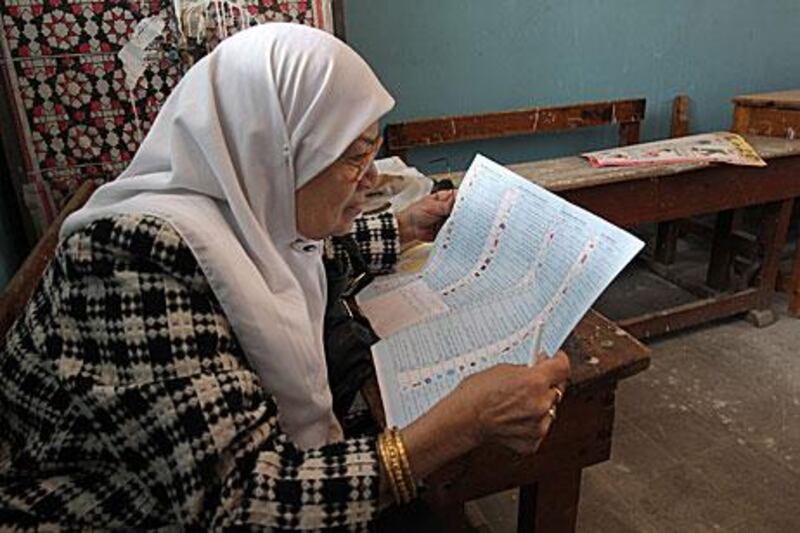

Amid the issues of history, theory and semantics, there is one thing on which most sides of the debate agree: without a new constitution, that argument can never be settled.

Since gaining independence in 1922, Egypt has been ruled by a succession of presidents who enjoyed wide powers over almost every aspect of life.

The result, in the case of Mubarak, was a regime characterised by tyranny, corruption and nepotism. As president, he amended Egypt's 130-year-old constitution three times to consolidate his power and prolong his rule.

Most of Egypt's political parties agree that to break with that past and ensure a different political future, a constitution is needed that enshrines a different role for Egypt's leader and limits the power of the presidency.

Where they disagree is on how much power should be conferred on parliament.

The Islamist groups who swept more than 70 per cent of the seats in elections to the People's Assembly are seeking a strong parliamentary system. It would ensure that their members had an opportunity in the next four years of their term to prove themselves strong legislators and press ahead with their idea of the "new" Egypt.

Other groups, including the liberal groups who won just a sliver of the seats - 14 per cent - in the assembly are pushing for a balanced system between the presidency and the parliament. Their hope is that presidential elections, scheduled to take place before the end of June, will produce a leader who will have the power to serve as a counterweight to the Islamist-dominated parliament.

"The balance of powers of the government will be one of the most debated issues in the constitutional committee," said Noha Bakr, a professor at the American University of Cairo. "I believe the members will be keen on limiting the powers of the president, but the question is what kind of system they will create."

At stake in the struggles over balance of power, in particular, will be how much of a role the military will be able to retain in such areas as foreign policy and control of its own budget, as well as such hot-button issues as the power of the judiciary and media freedom.

Khairat El Shater, deputy chairman of the Muslim Brotherhood, said in an interview published on Saturday on the group's website that the ideal arrangement for the parliament's oversight of the military would be to appoint a special committee to review the budget behind closed doors.

The constitutional debate will also touch on issues surrounding the Islamic nature of the country. This is not, however, expected to be hotly contested, especially after a broad coalition of political parties appeared to support a bill of rights put forth this month by Al Azhar University, the main centre of Sunni Islamic learning, to ensure freedom of religion and expression.

The writing of Egypt's new constitution will be complicated by the make-up of the committee assigned to draft it. Its 100 members will be chosen by the 788 members of the People's Assembly and the Shura Council, the lower and upper houses of parliament.

Even after Shura council elections are completed at the end of next month and the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (Scaf) has exercised its prerogative to appoint 100 members to the new parliament, Islamists will still hold most sway over the structure of the new government and who is appointed to the constitution drafting committee.

That does not mean there will be a unified Islamist stance over the content of the new constitution. The Islamist parties do not see eye-to-eye on every issue, leaving open the possibility that new alliances will form. Al Nour Party and its bloc, which control 24 per cent of the seats in the lower house, have struck an independent stance and said they would be open to voting for any laws or changes that advance their political platform.

Indeed, the initial sessions of the People's Assembly have shown that legislating will probably be bogged down by divisions. Mazen Hassan, a professor at Cairo University who is studying the current election process, said that so far the members of parliament have been in "heated debates about superficial things".

"They are focusing on things that shouldn't take that much time, like the exact phrasing of the oath and whether someone should get two minutes to speak on an issue," he said. "If they are disagreeing that much about this, what are they going to do when they debate the draft constitution?"

In other words, a "new" Egypt defined by a rewritten constitution that codifies more democratic political arrangements may be a while in coming. A revolution still awaits.

Follow

The National

on

[ @TheNationalUAE ]

& Bradley Hope on

[ @bradleyhope ]