It was almost midday when Father Paolo Dall’Oglio knocked on the gate of the Raqqa governor's building. The father, a meditative 58-year-old Italian who had been in Syria for years, asked the guards in front of the elegant brick building if he could meet the emir. After a discussion, they told him to come back after evening prayer.

It was summer 2013, and two years into Syria’s civil war, Raqqa was the sole provincial capital to have fallen since the start of the uprising. Earlier that spring, insurgent groups, ranging from Salafist to secular, had taken the city in a victory that had surprised even rebels by its speed.

By July, when Father Dall’Oglio was negotiating at the gates of the governor's building, an uneasy and fragile peace between a loose coalition of rebels held in the predominantly Sunni city. But already, ISIS fighters had begun kidnapping other rebel leaders. Later that summer, the group would launch its vicious takeover of the dusty town on the Euphrates which would become its capital.

Father Dall’Oglio was aware of the risks of approaching the extremist fighters, but a lifetime’s commitment to Syria, its people and the Gospel gave him faith. When the guards at the gate sent him away that evening, he again returned the next morning, July 29, 2013.

No one has heard from him since.

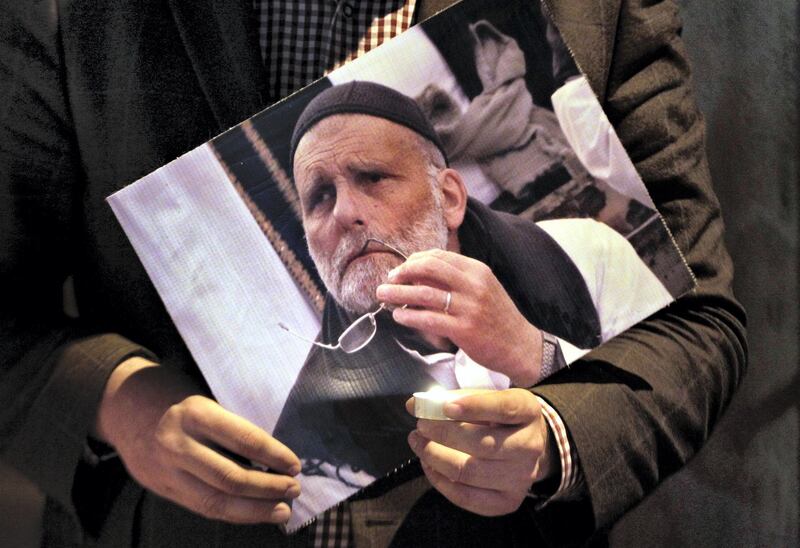

Even among the thousands of people who have gone missing during seven years of war in Syria, Father Dall’Oglio’s disappearance five years ago stands out. He is remembered today in Syria as the Priest of the Revolution, for standing with the protesters against tyranny.

Father Dall’Oglio is presumed dead. But a trip to Raqqa to retrace his last days reveals how the ideals of peaceful coexistence he represented have survived, in the work of friends and colleagues he left behind. Today, they still work to actively instill the values of tolerance that he preached.

Believing in Jesus, Loving Islam

As a young Jesuit priest in the early 1980s, Father Dall’Oglio came to Syria to study Arabic, a language he would eventually speak fluently with a local accent. In 1982 he discovered his life’s mission in the ruins of the sixth century monastery of Saint Moses the Abyssinian (Deir Mar Musa) in the hills north of Damascus. He fell in love with the stark beauty of the parched mountains and the dilapidated chapel with its ancient frescoes.

Inspired by Syria's century-old experience of Muslim-Christian coexistence, he decided to restore the monastery and found an ecumenical community. Deir Mar Musa became an international pilgrimage site which welcomed all comers of all faiths. Father Dall'Oglio became renowned as an activist for Christian-Muslim dialogue. He fasted in Ramadan and wrote a memoir titled Believing in Jesus, Loving Islam.

But by 2011, even from his idyllic retreat in the Qalamun mountains, Father Dall’Oglio couldn’t ignore the political situation in Syria. In the early days of the uprising, he spoke out against President Bashar Al Assad. Later he called on the UN to protect Syrian civilians from indiscriminate regime bombing. In June 2012, he was deported.

Father Dall’Oglio couldn’t stay away from the country to which he had dedicated his life. In July 2013, during Ramadan, he crossed the border from Gaziantep. He sent a last email to his Italian friends saying that he wanted to visit the first provincial capital to be freed from government control.

__________

Read more:

Raqqa's survivors search for the missing amid destruction of ISIS rule

Coalition attacks on Syria's Raqqa may have broken law, Amnesty says

UAE pledges $50m for stabilisation efforts in Raqqa

__________

He also had another mission. He hoped to persuade local ISIS commanders to halt the violence that was spreading across the city. “He insisted that he really wanted to go to speak with those commanders,” said Mona Fraig, a 37-year-old Raqqa activist and friend of Father Dall’Oglio. “We said, please be careful, don’t go, it’s risky.”

News of his arrival spread quickly. Many Raqqawis were surprised that a foreigner – and a Jesuit father, no less – would visit at that time. “Everyone knew who Father Paolo was,” one elderly resident recalled. “He was like a prophet coming here to spread the message of peace.”

Before Father Dall’Oglio returned to the governor's building on July 29, it wasn’t clear which militant group was really in charge there or in the city overall. Jabhat Al Nusra and the Salafist Ahrar Al Sham were the strongest militarily, but a host of smaller militias were also vying for influence. ISIS was one of them, although its name did not yet instill dread by its mere mention.

Regardless, Father Dall’Oglio was anxious. Before he left he paced up and down the courtyard at the home of a friend where he was staying. “At a certain point my father went to him and said, ‘Everything will be fine’,” recalled Eyas Diyes, a media activist who today lives in Turkey. “Father Paolo answered, ‘If they arrest me or you don’t see me coming back, wait three days before giving the alarm.’”

When Father Dall’Oglio didn’t return, Mr Diyes went to the governorate building with a friend. The fighters led the men to a basement corridor and left them waiting. Eventually, the emir came to them. “He wore an explosive vest and was accompanied by two bodyguards pointing their guns at us,” Mr Diyes told an Italian television journalist.

The emir's name was Abdul Raman Al Faysal Abu Faysal.

The men explained that Father Dall’Oglio was seen entering the governor’s building but the emir denied all knowledge. “At one point he said, ‘I swear I never saw him’. We knew that he was lying.”

Piles of rubble

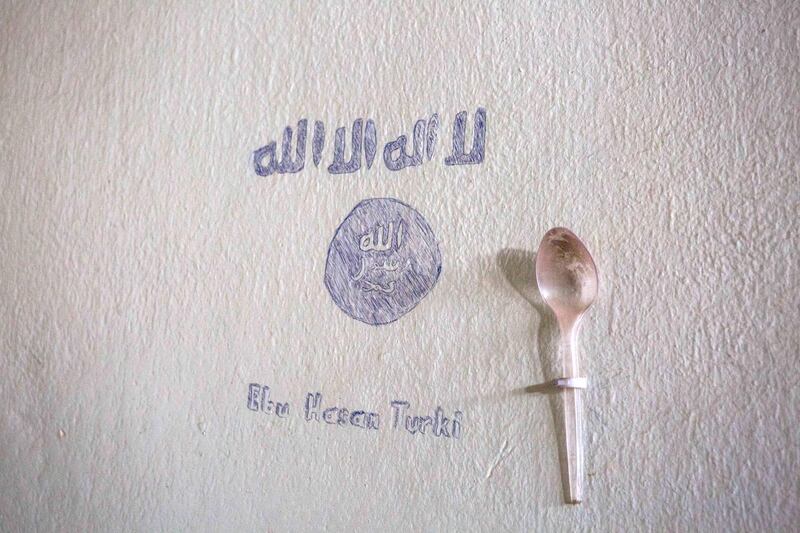

Raqqa served as the capital of the ISIS caliphate for more than three years until it was captured after a four-month siege in October 2017, by a United States-backed coalition of Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces. The battle relied heavily on US air strikes and today, much of the city is destroyed.

The building Father Dall’Oglio disappeared into five years ago is gone, its brick arches lying in piles of rubble. Even though ISIS lost its control, there is still no news of his whereabouts.

Local sources, who even today fear to speak publicly in case of retribution from ISIS sleeper cells, say Father Dall'Oglio was initially detained by two doctors affiliated with a small militant group Jabhat al-Wahda Al Tahrir Al Islamiya. The men, Samer Metiran and Adnan Sobhi Al Irsan, were allegedly present in a video posted soon after Raqqa's capture in March 2013, which showed rebels capturing the governor and local Baath party chief, both of whom were believed to have been later killed. Father Dall'Oglio is said to have been handed over to Abu Faysal.

Abu Faysal later became notorious as a key ISIS leader in Raqqa, accused of killing and torturing scores of civilians. According to the citizen journalist group Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently, Abu Faysal rose to the position of deputy of Raqqa and head of the local ISIS security forces.

In the fighting to retake Raqqa, thousands of ISIS fighters were killed, while others managed to escape, some crossing the border into Turkey. Abu Faysal stayed in the city and was eventually captured by Syrian Democratic Forces.

Inexplicably though, he appears to have later been set free.

“Abdulrahman has been sent to the court and here our role [the SDF] finished,” said Mustafa Bali, SDF spokesperson. “He spent some time in prison and after serving his sentence, he was released and now he lives in Raqqa.”

The Kurdish PYD, which runs its own court system in north-east Syria, was not immediately available to comment.

Local sources in Raqqa say Abu Faysal was set free after the intervention by a powerful tribe, upon whom the SDF relies to help rule over Raqqa. He is said today to live on the other side of the Euphrates under the protection of his clan, Al Afadila-Mousa Al Thayer.

He still commands the fear of locals living in Raqqa. Abdallah Arian, the vice-head of the Raqqa Reconstruction committee, warns to keep clear of him. “He is a criminal and he will not be able to tell you anything more than what is already known. Father Paolo is dead.”

Abu Faysal is perhaps the last person to have knowledge of Father Dall’Oglio, and with his escape, the odds of finding closure diminish. Few of Father Dall’Oglio’s friends in Syria believe he is still alive, but without a body to mourn or bury, it is difficult to accept reality. His family in Italy hold out hope, telling a television programme recently that now is the time for the Italian government to do something to uncover the truth.

Not far from the ruins of the governor’s building, a group of young activists are meeting in a two-storey house that somehow escaped the bombing that levelled much of the city. Many of them were friends with Father Dall’Oglio, and today work for local NGO Civil Society Support Centre, which organises workshops on countering violent extremism and radicalisation.

This is the legacy of Father Dall’Oglio, says Raqqa activist Ms Fraig.

“The disappearance of Father Paolo affected all of us here,” she says. “One of the reasons we came back was to spread his values: peace, tolerance and coexistence between people of different communities.”