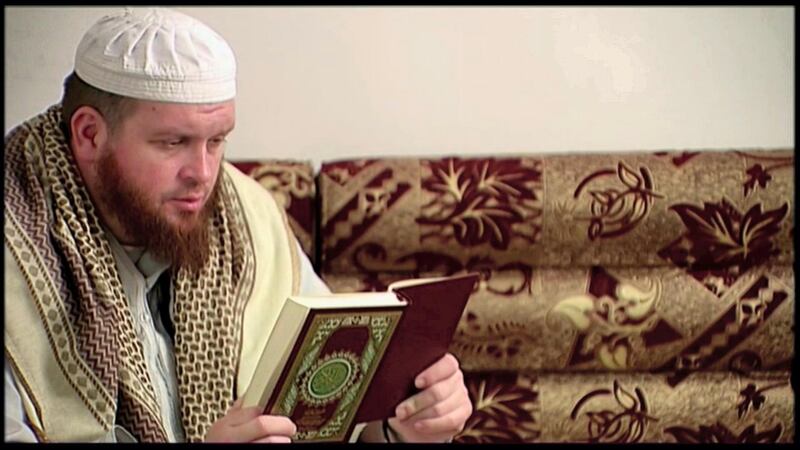

The following is a transcript of detained New Zealander ISIS member Mark Taylor’s interview with Campbell MacDiarmid, The National’s Assistant Foreign Editor, at a Kurdish prison in northeastern Syria, with filming by Willy Lowry. The transcription was prepared by Jack Moore and has been lightly edited for clarity. Read MacDiarmid's exclusive report and more on the last days of the Islamic State here.

Campbell MacDiarmid: Hi, Muhammad, my name is Campbell, I'm a journalist from New Zealand.

Mark Taylor: Ah, a journalist from New Zealand.

MacDiarmid: Yeh, when was the last time you spoke to New Zealanders?

Taylor: You mean the New Zealand government?

MacDiarmid: No, no, just it must have been a while.

Taylor: New Zealand reporter?

MacDiarmid: Yeh.

Taylor: I think it was around about November 2016.

Taylor: Which media?

MacDiarmid: I'm working for a newspaper called The National in Abu Dhabi...Emirati newspaper. You're happy to speak to us today?

Taylor: Any news about my government? Or no news?

MacDiarmid: I can tell you some of what’s happened in the past few days.

Taylor: Is it a no or yes? Or what?

MacDiarmid: Let me get Willy set up with filming then we can go on with the interview.

[BREAK]

Taylor: How long have you been out of New Zealand for?

MacDiarmid: About ten years working in the Middle East.

Taylor: You find it good eh?

MacDiarmid: I enjoy it, yeh.

Taylor: I've been out here for seven years now.

MacDiarmid: As I explained before, we are journalists from The National newspaper in Abu Dhabi, we understand that you have been willing to speak to us, you don't have to if you don't want to.

Taylor: I don't mind talking to you.

MacDiarmid: So how did a bloke from New Zealand end up where you are?

Taylor: So it's a long story.

MacDiarmid: Give us the short version to start with and see how we get on.

Taylor: I've been trying to get out for like the last three years and now I decided just to give up and now the time to get out when I was forced to get out with no food, no basic facilities, bombs dropping everywhere, 500-pound bombs dropping everywhere, mortars from the Syrian forces, everything.

MacDiarmid: So it didn’t turn out how you expected?

Taylor: At the beginning it turned out how I expected but at the end I was pretty much getting squished.

MacDiarmid: So what did you like about it when you came out here?

Taylor: I wanted to see the situation. I wanted to see the Islamic State. It wasn't actually when I came to Syria, it wasn't coming to the Islamic State directly. I actually went through Idlib and I spent some time with another group, Jabhat Al Nusra, and I only spent three months with them then I kind of defected to the Islamic State after the three months. From Idlib I went to Hama, from Hama I went to Deir Ezzor, Mayadin, Deir Ezzor city. Then I had some trouble with the Islamic State secret police, that's a short version.

What happened was I go back to Hama, spend some time guarding a ribat point, a border line between the government and the Islamic State. I go back to Raqqa, spend some time teaching English to some children, then after Russians blew up my school, well actually blew up several schools at the same time, then I became jobless and I didn’t want to work anymore. So I became more independent like buying, selling, scavenging through junk, rubbish tips, basically begging. It was actually more begging at the end. I had to go around looking for food.

MacDiarmid: So what date did you join ISIS?

Taylor: I left Idlib around about the 21st October 2014, it took about a day to get into their territory, I had to go through several checkpoints. It took about 20 hours or so to get to the desert of Hama.

MacDiarmid: So this was about the time they were taking Western journalists hostage and beheading them?

Taylor: That was before that, I came just after. That sort of thing is not really my problem. I didn't have concern about these situations. I'm talking about myself, I'm not talking about the Islamic State. What the people did in the Islamic State is their problem. What happened there had no concern with me.

MacDiarmid: So you don’t feel like actions taken by the Islamic State you have any responsibility for?

Taylor: It's not my responsibility. I came to see the situation and see if it was an Islamic State or not.

MacDiarmid: And you left after four years because you were hungry and there were no services?

Taylor: I was starving actually. No basic services. Most of the services were bombed out or destroyed by heavy shelling or heavy bombs.

MacDiarmid: So you were pretty committed then to stick around for that long?

Taylor: That's right.

MacDiarmid: So if ISIS were still strong you’d still be living under them?

Taylor: Well it depends on the situation. But see ISIS is not really ISIS. They call themselves now the Islamic State. It's a worldwide phenomenon. It's not just based on one area, it's based everywhere.

MacDiarmid: I think we are talking about the same organisation.

Taylor: Yeh.

MacDiarmid: So why didn’t you fight until the end then?

Taylor: I didn't fight to the end. I walked out. I surrendered myself to the PKK (Kurdistan Workers' Party).

MacDiarmid: You didn’t want to die for the caliphate?

Taylor: No. What's the point? What's the point when there's a B1B [bomber] flying over my head? 15 kilometres above my head. And I look up and the hatch is open and... ah ...maybe one minute I'll be dead. Two minutes. Half an hour. That's what it was like.

MacDiarmid: Was there anything about ISIS that you disagreed with?

Taylor: Yes, I did.

MacDiarmid: Talk to me about that.

Taylor: After Mayadin, everyone was getting pushed back. To the point where everyone was from Raqqa, or Halab (Aleppo). They were getting pushed down all the way to Mayadin. That didn't last very long. That lasted say four, five, six months until the Syrian forces took Deir Ezzor until they basically started attacking Mayadin. From there, they pushed everyone out of Mayadin then to [inaudible] to Abu Hamam, all the way down to Hajin.

MacDiarmid: What about policies? Were there any policies under the Islamic State that you disagreed with?

Taylor: The thing was I was kind of upset...I mean they put me in jail for one GPS location on Twitter, after I left Hama. I was on holiday. I wanted to voice my freedom of speech. But it turns out that freedom of speech was not allowed in the Islamic State.

MacDiarmid: You must have known that before you went in?

Taylor: No. I had no problem when I spoke about it when I was in Jabhat Al Nusra, when I was in Idlib. But when I was in the Islamic State it was a different story. But because of certain people in the media, they decided to tarnish me and put me down. I ended up being put in jail for 50 days, accused of being a spy, thanks to these people.

MacDiarmid: So you are upset about the way you have been covered in the media?

Taylor: That's correct, yes. Quite upset.

MacDiarmid: Do you feel bad about the way the Islamic State has treated any other people, other than yourself? What about the Yazidis?

Taylor: I wasn't involved directly in that because I was around Hama and Deir Ezzor.

MacDiarmid: I'm not saying you were involved in anything that happened to the Yazidis, but what's your opinion of the way the Islamic State treated the Yazidis?

Taylor: I really don't know. But I think they were kinda harsh on the situation. They could have been more easier, more fair. But I don't know the full extent of the damage. I know there was a lot of damage that happened there.

MacDiarmid: Well I can tell you because I have been to Sinjar. I’ve seen the mass graves there, I’ve interviewed families whose women were taken into slavery, raped repeatedly, sold from one fighter to another up to 17 times.

Taylor: That's a lot.

MacDiarmid: So you said you were like a guard for ISIS? Were they interested in your military background?

Taylor: Not really as such, because I told them because I mostly specialised in security work. Even before I came to Syria, in New Zealand and Australia I was working in private security. So most of the work I actually did in the military wasn't that special really, mostly labouring, mostly guarding work, guarding duty and stuff.

MacDiarmid: And you made some propaganda videos.

Taylor: Yeh.

MacDiarmid: Do you want to come back to New Zealand?

Taylor: I have no problems going back to New Zealand. What can I do here? What do I have that can be offered here for me? More prison time? More what? I don't know.

MacDiarmid: You asked me what the New Zealand government response has been to you that you’re here. I can tell you yesterday that our Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, she said they are not going to strip you of your citizenship but they are not going to help bring you back. They said they don’t have diplomatic relations with the SDF. They said Syria is a dangerous place for New Zealanders to come, their travel advice is against any New Zealanders coming to Syria, they said they don’t want to risk any New Zealand lives to come and get you back. She said if you can get yourself to a New Zealand embassy, I guess the nearest one is Turkey, they will issue you a travel document for you to come home.

Taylor: So how do I do that? How do I leave here and go to Turkey that is the question?

[LONG PAUSE]

MacDiarmid: What do you think?

Taylor: The hard part is leaving here and going to Turkey.

MacDiarmid: It is.

Taylor: Maybe I go to Turkey and maybe they arrest me at the border, I don't know.

MacDiarmid: Do you feel like you are owed anything by the New Zealand government?

Taylor: No. I was hoping at least a government agency would at least pick me up and take me home. I was expecting that. Because I contacted New Zealand intelligence and they asked me to leave. And I left.

MacDiarmid: One of your tweets from 2014 said I have abandoned all international laws and you only practice Islamic Sharia laws. New Zealand laws are the worst of all time. Sorry Jonhy, here to stay in IS.

Taylor: That's correct.

MacDiarmid: So I mean you have abandoned international laws. Do you think international laws should abandon you or still apply?

Taylor: Well that happened over four years ago and my opinion before I went into prison was like that. But after prison my opinion changed.

MacDiarmid: Talk me through that. How has it changed?

Taylor: Because the situation, by being placed in jail, in a secret prison and being accused of being a spy changed me completely.

MacDiarmid: So you felt hard done by, by ISIS, they didn’t treat you right?

Taylor: That's correct.

MacDiarmid: So it was that more so than any of the executions or anything else that sort of changed your mind about ISIS?

Taylor: See the thing is, they decide who lives and who dies. I happen to be very lucky. People were telling me when I got out 'oh, you're still alive, you haven't been killed.' So getting that type of response from people made me very upset. I did regret making statements on Twitter.

MacDiarmid: Yeh, they are a bit incriminating now.

Taylor: Yes.

MacDiarmid: Now, ISIS doesn’t really hold any more territory in Iraq or Syria. It has sort of collapsed. Has that kind of shaken your faith in whether or not ISIS was on the correct path in terms of interpretation of Islam?

Taylor: There's too much corruption in the Islamic State. After the fall of Mayadin (in 2017), basically there wasn't an Islamic State after that, it became the mafia state.

MacDiarmid: Did you see any public executions?

Taylor: From time to time. You have a large crowd gathering around. You have... they've hurt someone. Either shoot him or shoot her. Put them on the back of a truck and drive off. That for example. Or people crucified. They had someone crucified with an Arabic notice on their chest.

MacDiarmid: What was your reaction to that?

Taylor: I was kind of devastated, that this could have happened to me too. But the thing is, I knew some people who were actually put away because of freedom of speech for seeing injustice in front of them.

MacDiarmid: Why would there be freedom of speech under ISIS? Where is that enshrined? That’s a Western value.

Taylor: It is. It's not an Islamic State value.

MacDiarmid: Looking at coming home, which of your values do you think are compatible with New Zealand society?

Taylor: Business. I was looking at going home to do some business. There might be a chance of legalising marijuana. They are looking at a referendum to legalise marijuana. I was looking at a business idea where I can do a plant and food business with marijuana. That's if it's legal. But it might even take a year or two to get it through parliament.

MacDiarmid: So what’s your view of the legalisation of cannabis?

Taylor: I did some research. I found that medical-grade marijuana is in a sense can be halal under Islamic Sharia, depending on how it is applied.

MacDiarmid: Things that alter the mind though are not typically permitted under Islam.

Taylor: It depends on the quantity. If you take too much it becomes into altering the mind. I saw a documentary from CNN that even a 5-year-old girl was taking medical marijuana for epilepsy.

MacDiarmid: So if you had a future you would be interested in coming back to New Zealand and looking into some kind of medical marijuana business?

Taylor: If marijuana is not legalised then the other option is maybe a coffee business.

MacDiarmid: You must know that the average New Zealander is going to be pretty concerned about you coming home. You called for attacks on ANZAC Day.

Taylor: Well, I didn't actually call for attacks on ANZAC Day, I called for attacks, but it wasn't for specifically ANZAC Day. But you have to realise that there are even more hardened people and hardened criminals have been kicked out of Australia, their visas cancelled due to violent crimes and sent back to New Zealand and they are much more worse than me.

MacDiarmid: Have you got family and friends back in New Zealand still?

Taylor: Yes.

MacDiarmid: Are you in touch with them?

Taylor: I was in touch with my aunty before I left the Islamic State. I told her I will probably be spending some time in a jail cell if I survive getting past the border between the Islamic State and the PKK.

MacDiarmid: So to what extent do you feel like your actions are responsible for you being in this position now?

Taylor: That's correct. That's absolutely right. It's my full responsibility that I have come to this stage. I thought I would have been dead by now.

MacDiarmid: Do you feel like you might have been a bit sort of…

Taylor: ...adventurous?

MacDiarmid: I mean were you a bit of a follower coming into this? Did you buy into it a bit too much?

Taylor: What do you mean?

MacDiarmid: Do you feel like you did your due diligence before you came and joined the Islamic State?

Taylor: I did my own research to see if it was the Islamic State. And I feel at the time it was the Islamic State as I saw it. But after the fall of Mayadin, it changed. Even after I got released from prison in March 2015, I had a different view of the Islamic State. I wrote a letter in prison making a complaint that the Islamic State oppressed me. I mean soldiers came to me and told me "you must love the Islamic State", and I said "how can I love the Islamic State when they oppress me like this?"

MacDiarmid: So up until that, when you first came in, that was the right choice for you at that time?

Taylor: Yes.

MacDiarmid: And then after they imprisoned you, you had some issues with the Islamic State?

Taylor: Yes. That's correct.

MacDiarmid: You were living in New Zealand and Australia for a long time. What about that didn’t really satisfy you or didn’t work for you?

Taylor: After I became a convert Muslim, I realised that I needed support. I lived in Brisbane in Queensland for about one and a half years as a convert between 2002 and 2003. Then I decided to move down to Sydney to look for better opportunities to get better support as a new convert. I spent the rest of my time in Australia in Sydney.

MacDiarmid: So you wanted to be around people who shared the Islamic faith?

Taylor: Yes.

MacDiarmid: In your view, the sort of...in 2014 when you joined Islamic State, was the group following Islam the closest as you understood it?

Taylor: When I researched it seemed to be the closest because the situation in Idlib with Jabhat Al Nusra, I saw a situation where some of Jabhat Al Nusra were actually captured on the guarding point by Army of Islam and they thought they were going to be killed and instead the Islamic State talked to them and said they are brothers and they let them go after four hours. I'm thinking well if the Islamic State is doing this to Jabhat Al Nusra I should go ahead and have a look for myself.

MacDiarmid: Do you then feel let down by ISIS now?

Taylor: I feel I have been let down by ISIS now.

MacDiarmid: How did you feel when they were getting bombed and [ISIS leader Abu Bakr Al] Baghdadi was nowhere to be seen?

Taylor: Well, there was a process. For the last three years or so, we moved back and forth being bombed by the Syrian government and the coalition. That's true, not seeing the caliph. But the caliph, he can not be seen. Because if he is ever seen, he will be assassinated by some type of drone or some type of heat-seeking missile by the coalition. This is why he is under hiding, 100 per cent.

MacDiarmid: There hasn’t even been an audio message from him recently.

Taylor: There hasn't? I've been in jail for like 10 weeks now.

MacDiarmid: So when you surrendered, what instructions did ISIS give you about surrendering?

Taylor: They didn't. I just walked out.

MacDiarmid: No one stopped you at that time?

Taylor: I walked around that area looking for a way out for the last couple of weeks at that time, after everything started collapsing. And some people were telling me if you leave you're going to become a kafir (disbeliever). They were trying to scare tactic me. They would say the PKK, they are going to end up killing you. Torture you. Beat you. That's the fearmongering they were doing to me. I said look, I pray to God to go out, then I just went out. I got some advice from people, they were telling me it's 50/50. You have to make your own way out.

MacDiarmid: What was your life like before you found Islam?

Taylor: I was quite an arrogant individual you could say. I'm actually more like a loner individual. I keep myself to myself a lot. Don't interact with much people. But at the same time I was also researching about other religions.

MacDiarmid: How did you get on in the army?

Taylor: I had quite a few people who didn't like me in the army.

MacDiarmid: How come?

Taylor: My attitude. My character was different. You could say I was a born again Christian. Not many people like born-again Christians, especially one that want to practice their religion in the army.

MacDiarmid: What was your childhood like?

Taylor: I would say growing up in a Middle Class family. Basically what happened was when I was eight-years-old I moved to Australia with my parents, me and my brother, we did some schooling, in secondary school. I fall out of high school. So around about 15-years-old I get a job working the coast of Queensland, working on a fishing boat, a prawn trawler, so I work on that job for approximately four months, then I fall out of that job.

Then I spent some time unemployed. Then I find another job working for another fishing company, so I spent about two years doing that. So that’s up to 1992. Then I worked for a building company for about six months learning how to be a tradie, but the guy told me he couldn’t afford to keep me on anymore. So eventually by 1994, I become a born-again Christian. I want to go back to New Zealand and sort my life out.

So I go back to New Zealand. In 1995, I go into the territorials, into the infantry. Did a year and a half in the territorials. I transfer into the regular army, I transfer into artillery. Gun specialist trade. Mostly operating computers, radios, radar, also the casual gun from time to time but that was about it. Also guarding as well, on the camp, on the base, exercise five times a week. After there, I had a messy separation with my wife, my wife runs away with another man.

After being a born-again Christian and having a messy situation with my wife, I actually become an Atheist for 16 months. This happened around 1998 to 1999. After that I become a Christian again but an open-minded Christian. I was very interested in different denominations but it wasn’t really set. That’s when it started to occur to me about Islam. It actually happened around 1999.

MacDiarmid: It sounds like you have been through some changes and developments in your life, do you think you would ever change your mind about some of the beliefs you have had regarding Islam and living under the Islamic State?

Taylor: In the Islamic State, I was allowed to practice at least 100 per cent Islam. But after the fall of this area, where else can I go? My government doesn't want to help me to go back. Now I have to fend for myself to return back.

MacDiarmid: There’s a lot of different interpretations of Islam and most practicing Muslims don’t agree with the idea of slavery, for example.

Taylor: That's true. Well, slavery I find is not much a problem really.

MacDiarmid: You’re okay with it?

Taylor: There's no problem. As long as you treat the slave as equal, as mentioned in Sharia law. You don't treat them as sub-human, you treat them with respect as a human.

MacDiarmid: You must know that virtually everyone in New Zealand will have a real problem hearing that.

Taylor: Well, it's not really my concern. If they want to get their pitchforks out and start going burn him on the cross or something then that's a bit of a concern too. I've had people before threaten to kill me if I ever return back to New Zealand. One article I saw with comments, every second or third comment was people threatening to kill me, I was surprised at how military New Zealanders can become. People who have no tolerance towards religion for example. I thought New Zealand was supposed to be a tolerant country.

MacDiarmid: I don’t know if we’re supposed to tolerate slavery.

Taylor: Well, that happened during the time of the Islamic State.

MacDiarmid: What was the best time in ISIS for you?

Taylor: The best time was coming to the Islamic State and seeing a different situation. To see how people treated me. I found that very interesting that people were actually treating me quite good. Especially from the Syrians, they were showing a lot of respect towards me because I came from New Zealand, very surprised.

So that’s probably one of the main reasons why I stayed in the Islamic State because of their courtesy and manners. In New Zealand they don’t have that as such. I remember walking down the street in New Zealand and someone say ‘Hey, what are you looking at? You want to fight me huh?’ I was just walking down the street looking for an address, and this guy wants to pick a fight on me. I thought New Zealand was supposed to be one of the safest countries in the world. And you have someone walking down the street who wants to pick a fight with you. I come back from Australia and you get people coming out like that out of the blue, and I’m just looking for a shop. No tolerance.

MacDiarmid: So you felt like you were belonged and welcomed when you came here?

Taylor: Yes.

MacDiarmid: Was that the first time in your life you’ve had that feeling of belonging?

Taylor: That's correct. Because I didn't feel like that in New Zealand. I thought New Zealand was supposed to be a tolerant country where they tolerated other people's beliefs. When I saw Australia, I thought Australia was more tolerant than New Zealand. I was kicked out for no particular reason.

MacDiarmid: What was that story?

Taylor: Australian intelligence services decided to cancel my visa in Australia in 2010 and they won't tell me why.

MacDiarmid: Related to your trip to Pakistan?

Taylor: Yemen. More likely Yemen.

MacDiarmid: So you’d been trying for some time to join groups you felt had an interpretation of Islam that aligned with yours?

Taylor: Nope. I was more interested in finding a community to live in and say 'right I can practice my religion within the circle 100 per cent' that's what I was looking for. Pakistan and Yemen was those reasons. Instead I actually ended up living in Indonesia.

Taylor: I just want to ask ya, is the New Zealand government, they are offering me a travel passport back to New Zealand or is it an open passport?

MacDiarmid: I think they are not offering you anything. But they have said they are legally obligated if you turn up at a New Zealand consulate to provide you documents to travel back to New Zealand.

Taylor: So only New Zealand? So I can't go to Indonesia? Okay, I'll have to go for New Zealand then.

MacDiarmid: I mean I think the subtext though was that you were not going to be able to do that under your own power and the New Zealand is satisfied with the situation of you remaining where you are for the indefinite future.

Taylor: This prison? Or some other location?

MacDiarmid: So Winston Peters who is currently the foreign minister said: 'You've made your bed and now you need to lie in it'. [It was actually New Zealand Police Minister Stuart Nash who made this statement. Mr Peters has said: "We couldn't give a rats derriere about him - deserting his country, threatening Western civilisation and the freedom of democracy and human rights altogether, plus being a bigamist."]

Taylor: Gee, that's pretty hard.

[LONG PAUSE]

MacDiarmid: Is there anything else you want to talk about?

Taylor: The thing is, I thought New Zealand was going to give me a fair go. I know New Zealand helped me before in Pakistan, by getting me out of Pakistan, but they had a consulate in Pakistan. They helped me out when I was in Australia when I complained about Australian government cancelling my visa. I sent an email directly to the New Zealand government to complain. The only option was for me to get deported from Australia. But they had minimal help on that. The funny thing was I found that I actually received my passport from the New Zealand government after three weeks of arriving back in New Zealand even though they cancelled my passport, I found that quite strange. But I understand they are not willing to send someone to... get a representative. So how can I get out of here when there is no representative to actually...no one to even help me at all. I'm just one person. What can I do? What can I do now in life? I have to stay indefinitely in some prison cell that I don't know. Even getting to Turkey. What's other places I could go that has a New Zealand consulate.

MacDiarmid: I don’t know mate. I can only tell you what I know.

MacDiarmid: If you could give a message to anyone, what would you say and who would you say it to?

Taylor: I would say it to my aunty, Aunty Elizabeth, who was a firm supporter of helping me in the past. She's my mother's sister. I just want to pass the message that...I'm trying to put pressure on the New Zealand government to try and help me to at least leave Syria and try to find a way to get out. I have no money. When I left the Islamic State, everything was taken from me. The PKK stripped me only down to my pants and my trousers and my underwear. Everything was gone. Almost everything. Especially in Syria, I've lost everything.

MacDiarmid: Yeh, a lot of people here have lost everything.

Taylor: Yes. I just want my Aunty to try and ask the government. Because I asked the government to help me. But then eventually, they just stabbed me in the back. It feels like they stabbed me in the back.

MacDiarmid: Stabbed you in the back? How?

Taylor: I thought I was under the impression that at least they could come at take me out of here.

MacDiarmid: But you burned your passport. It was a symbolic act of renouncing your New Zealand citizenship it appeared.

Taylor: I burned the passport. It happened when I first arrived in Syria back in June 2014. Then I realised I made the mistake of actually burning it. That was my mistake.

MacDiarmid: Is there anything else you want to say?

Taylor: I just want to say that... it was my decision to come here. It's my fault that I came here and, as I said before, it's life experience, I'm going to have to live like this. But I need to find out how to get out of jail. Even if I have to go back to New Zealand for a travelling passport, or even go to Turkey.

MacDiarmid: Is there anything you want to ask me?

Taylor: Erm. No I'm fine thank you.

MacDiarmid: Thank you for your time.