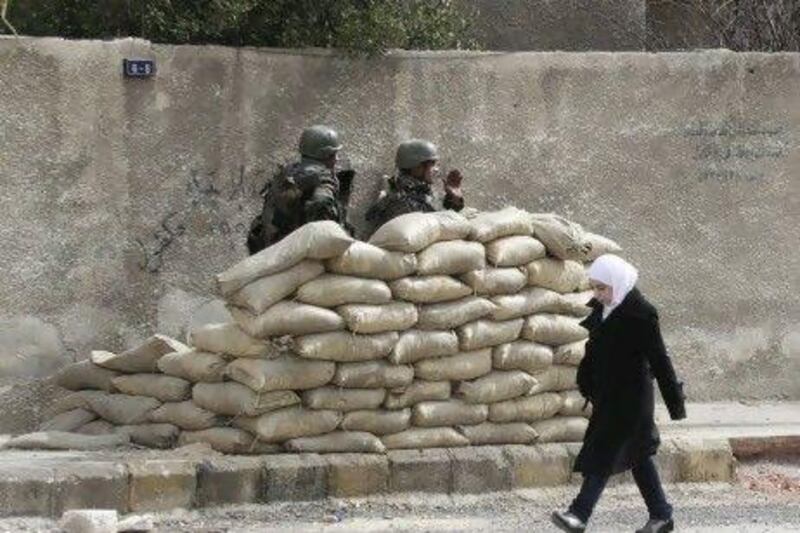

DAMASCUS // As Damascus turns into a city at war, it is also turning into a city of checkpoints.

In these violent times they have become an inescapable fact of life for residents of the Syrian capital, every bit as much as unemployment, long searches for overpriced cooking gas and waking up to the thump of artillery shells or stutter of machine gunfire.

A source of fear to many, a source of comfort to others, there seems to be widespread agreement in this deeply divided country on at least one point - that checkpoints are an inconvenience for all.

While ostensibly uniform in their purpose - to monitor people and vehicles passing along a particular street - checkpoints are wildly different in character.

At some, bored government troops dressed in odd cocktails of army fatigues and civilian clothes - memorably, one solider in combat uniform and a black fedora worn at a jaunty tilt, with large, round film star-esque sunglasses shading his eyes - hardly bother to inspect anything.

They sit on plastic garden furniture next to rubble, wood and old tyres that have been thrown in the road to block traffic, make tea and ignore the passing vehicles. Occasionally these conscripts will stop passers-by for a glance at an ID card hoping to cadge a cigarette, some phone credit or a bottle of water.

Although slowing traffic to an unruly, bad-tempered crawl, especially on the highways into and out of the city, these checkpoints are not considered too bad.

Even the opposition sympathise with the soldiers given the chore of manning them. "They boil all day in the sun and at night they're afraid of getting attacked and their officers don't care if they live or die," said one activist who, despite his criticism of the armed forces, often carries snacks and drinks to give to the rank-and-file troops.

Rebel fighters also say they usually leave these checkpoints alone, sparing their efforts to attack those that are more strategically placed and zealous in their work.

Some checkpoints do have fearsome reputations. Qaboun, a neighbourhood of eastern Damascus that had been heavily involved in the initial protests and, subsequently, the armed rebellion, and that is also home to military police, special forces and Republican Guard bases, is notorious for having among the worst in the capital.

The outer cordon of soldiers around the district is feared by many residents. But it is the inner system of checkpoints, policed by plainclothes security forces and a locally recruited militia - many of them members of the ruling Alawite sect, according to people living in the area - that creates real dread.

Those manning them are notorious for pulling young men out of minibuses and either beating them senseless by the side of the road or dragging them away into detention, never to be seen alive again.

"The army are OK but the shabbiheh [pro-regime militia] have started looking at IDs and if they see you are from one of the original Qabouni families, they take you and you are never seen again," said one Qaboun resident in his late 20s.

He recounted almost being dragged off by the militia, until one of its members recognised him and remembered he was a regime supporter whose father serves in the military.

It is not only the authorities that set up road blocks, rebel groups have also taken to the idea, and, like their government counterparts, different areas have different reputations.

For a while Spaina, a tough, working-class industrial district on the southern fridge of Damascus, was a cause for frequent complaints, with drivers saying the Free Syrian Army was checking IDs in a sectarian vetting process to weed out Alawites who would then be taken away and seen next as corpses.

The proliferation of checkpoints has changed the geography of Damascus, and the passage of time in the city.

Drivers try to work out routes allowing them to bypass road closures, particularly bad checkpoints or those causing long hold ups, while journeys are now as likely measured by number of checkpoints involved not actual distance, as the former has much greater effect on travel time.

"There used to be no checkpoints between my house and my office, then there was one, then two, now there are at least six, sometimes eight with tanks and armoured vehicles," said a government employee who lives in the southern suburbs and works in the city centre.

Checkpoints are not always unpopular however, especially those surrounding communities of Christian, Druze or Alawite minorities, many of whom live in fear of the predominantly Sunni uprising. Often policed by local men, with official permission to carry shotguns and rifles, they let in residents but search unfamiliar cars for weapons.

"We don't want the fighting to come here, so if the checkpoints stop that happening and keep us safe, that's fine with me as long as they are respectful and behave well," said a resident of a predominantly Druze and Christian area on the edge of the capital.

The number of checkpoints in and around Damascus fluctuates from day to day. A short stretch of road may be clear in the morning, only for three or four to spring up there a few hours later. Each may check IDs, none may, or there will be a mix. Some can be polite, tidy and efficiently run, at others the soldiers are arrogant or rude, insulting drivers and forcing them to wait by the side of the road for no apparent reason.

"It's a lottery, you can go through nine checkpoints and everything will be fine, then you'll get one bad soldier who can destroy your life," said an electrician who travels throughout the capital and its suburbs. "Each time you go through one, you hold your breath a little and pray that today they don't want to make trouble," he said.

psands@thenational.ae