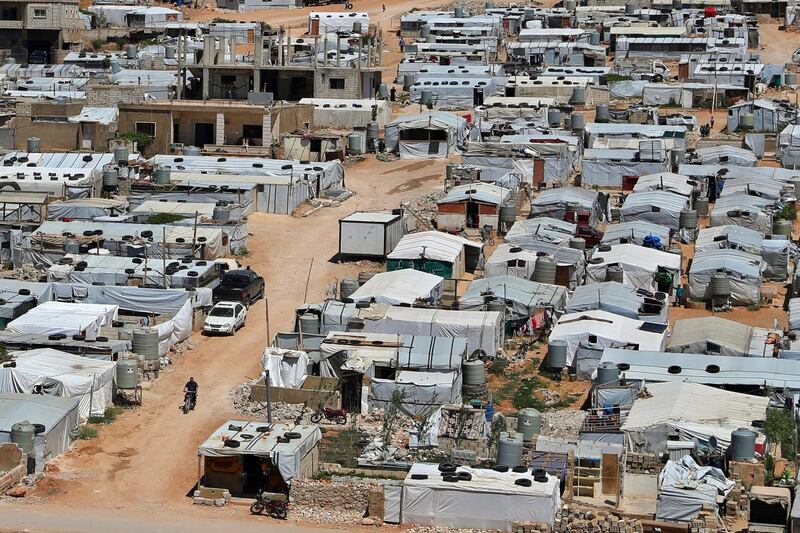

Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah’s call for refugees from Syria's Qalamoun to return to their villages was ignored this week in the Lebanese town of Arsal, which hosts tens of thousands of Syrians.

Most of them fled fighting between the Syrian regime and the opposition in 2013.

In 2017, the last pockets of ISIS and Jabhat Al Nusra fighters were pushed out of the region in a vast offensive on both sides of the border.

"There may be no more clashes today in Qalamoun but there are still real security concerns," a refugee doctor in Arsal told The National.

About 60,000 Syrians, most of them opposed to Syrian President Bashar Al Assad, live in Arsal, in north-east Lebanon.

Locals say that about half of them came from the Syrian region of Qalamoun, a few kilometres across the border.

"Return is sometimes synonymous to death," said Abu Rami, a local charity employee who fled his home town in Qalamoun because of regime bombing in 2014.

Hezbollah fighters played a key role in supporting the regime during the battle.

“Whether they are with or against the regime, people might be arrested by the Syrian authorities or attacked by their neighbours who sense an opportunity for material gain,” Abu Rami said.

Like other Syrians in Lebanon, he said he heard rumours of retaliatory attacks and imprisonment from some of the several thousand who returned home over the past two years.

Lebanese authorities have repeatedly dismissed these claims.

Nasrallah said on Friday that Syrians from Qalamoun were welcome to register for return with Lebanon's General Security intelligence branch.

“If anything is needed from Hezbollah, any help, any participation, any service, from us, we are ready,” he said.

The return of Syrian refugees has become highly politicised in Lebanon, with President Michel Aoun’s political party, the Free Patriotic Movement, aggressively calling for them to return to Syria because they are a burden on the economy.

The Higher Defence Council, which is led by Mr Aoun, decided in April that all Syrians who entered illegally from then on would be immediately deported.

Many analysts believe Nasrallah’s comments are another attempt to increase pressure on refugees to leave.

“Hezbollah, Syria and Lebanon want to show that areas under the control of the Syrian government are now 'safe', so that the presence of refugees in Lebanon is no longer legitimate,” said Cilina Nasser, an independent Syria researcher.

Another independent analyst, Aymenn Al Tamimi, said: “By inviting Syrians to go back home, Nasrallah is playing in part on anti-refugee sentiment to bolster Hezbollah’s popularity in Lebanon."

Figures on the number of returnees vary. This month, Mr Aoun told the US assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern affairs, David Schenker, that 352,000 Syrians had returned voluntarily “without facing any problems”.

That figure is about a third of the total number of Syrians registered with UNHCR, the United Nations refugee agency.

But Lebanese officials believe there are as many as 1.5 million Syrians living in Lebanon.

The UNHCR has only been able to verify 40,224 spontaneous and organised returns in total between 2017, when the Syrian war started winding down in favour of Mr Al Assad, and July.

In his Friday speech, Nasrallah said that there was no "demographic change" along the Lebanese-Syrian border, alluding to claims that Shiites were replacing Sunnis who fled the region.

“There is nothing of the sort,” he said.

While there is no doubt that Hezbollah has cemented its influence in Qalamoun, the group has not gone as far as to engineer demographic change, Mr Al Tamimi said.

He has recorded cases of Hezbollah setting up auxiliary forces of several hundreds of men who then became officially affiliated to the Syrian army.

Most Syrians in Arsal said that despite the increased pressure from Lebanese politicians, they would return to Syria only with UN protection.

“It will take more than calls by politicians for Syrian refugees to return, particularly calls from Hezbollah who fought fiercely and defeated armed opposition groups in Qousseir in 2013,” Ms Nasser said.

Last December, the UNHCR representative in Beirut, Mireille Girard, said the agency was discussing co-ordinating returns with Damascus on condition that returnees receive several guarantees that have not been respected up to now.

They included full access to their property and waiving mandatory Syrian military conscription for men aged between 18 and 42.

About a year later, the discussions are continuing.