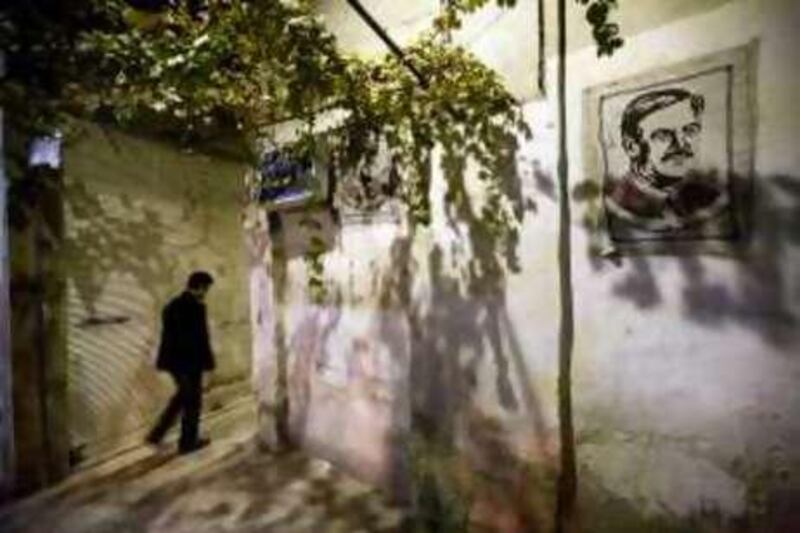

DAMASCUS // Syria's imposing statues and ubiquitous poster-portraits serve as a constant reminder of the late president, Hafez Assad, physical relics of a man whose spirit remains woven into the fabric of this country.

More than that, he remains indelibly part of the Middle East's turbulent political landscape. Today is the 10th anniversary of his death and his legacy still pervades the region. Hafez Assad's political views were forged in 1967 when the Arab world was crushed by Israel in the Naksa, also known as the Six Day War. After assuming control of Syria in 1970, he spent the next 30 years trying to overturn that defeat.

With Arab land, including Syria's Golan Heights, still under illegal Israeli occupation, Assad refused to walk the path of compliant moderation taken by Jordan and Egypt, both of which signed peace deals with Israel. To him - as to most of the Arabs - Israel was a project in violent colonialism, funded and armed by modern western imperialists, and intent on expansion. He saw himself as the only real obstacle standing in the Zionists' way, the champion of Arab rights.

Under his rule, all means were deployed in opposition to Israel, often at great cost to his own country. Following the limited success of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, in which Damascus won back a sliver of the Golan, a subtler foreign policy became Syria's major currency. Assad, born into a poor rural family in a small village, grew into a masterful practitioner of the dark arts of international politics.

During the Cold War he sided with Russia as a counterweight to the US-backed Israel. Despite being out-gunned and out-financed, he held his line against Israel, stopping its brutal efforts to install a pliant regime in Lebanon in the 1980s and undermining Israel's bloody suppression of Palestinian nationalism. In doing so, he cemented Syria's continued support for Palestinian militant groups and allied with Iran, a lingering bone of contention internationally as fear mounts over Tehran's alleged nuclear weapons programme.

This single-minded focus on the Arab-Israeli war overshadowed domestic policy-making. Assad saw himself as the only Syrian of his era capable of making a principled stand for the Arab cause and, therefore, built the state around sustaining his rule. A personality cult bloomed, political dissent was stamped out and opponents ruthlessly dispatched by his feared secret police networks. The economy was run on socialist lines, heavily subsidised and by modern standards utterly dysfunctional. But it generated just enough wealth, and spread it just far enough, to ensure a broad base of acceptance of his regime.

Assad did not live to see victory. Syria remains at war with Israel, its territory still under occupation. But the late president's unswerving devotion to the cause, and some of the tools he used to fight for it - including Hizbollah and radical Palestinian groups - were passed on to his son, Bashar al Assad, the man who succeeded him after his death. There have since been changes inside Syria, some breaks from the Hafez legacy. The ailing economy is being reformed and suppression of pro-democracy movements is less brutal than it once was, although critics of the new president say that, while undeniably ruling with a softer touch, he shares his father's intolerance of internal dissent.

The foreign policy foundation stone laid down by Hafez Assad remains firmly in place however, that core principle of defying Israeli dominance, refusing to kneel before Washington and Israel despite their economic and military power, and refusing to accept that Israel has the right to seize land by force. Assad had a golden rule, one his son and allies continue to adhere to; real peace with Israel - and therefore the only peace deal worth signing - should restore the region to its pre-1967 borders and be comprehensive, resolving the interlinked Syrian, Lebanese and Palestinian problems together.

Repeated, and for the most part half-heated, attempts at concluding a Middle East peace have never met those criteria and it has become fashionable, at least in certain influential circles, to view Israel's conflict with Syria as distinct from its conflict with the Palestinians. For those reasons, among others, peace is still elusive. While Syria cannot claim to have won, Israel has also failed to secure the victory it hoped for.

In his biography on Assad, the journalist Patrick Seale asked the former president how best to conclude his life story. He was told: "Simply say that the struggle continues." psands@thenational.ae