While Washington struggles to kick-start the troubled Middle East peace talks, its efforts are being undermined by steps Israel has taken in recent weeks on the most incendiary issue of all - Jerusalem.

The latest such move was Israel's passage of a law this week that calls for a national referendum before occupied East Jerusalem can be handed over to the Palestinians, who claim it as the capital of their future state.

Israel's parliament approved the referendum measure as the Obama administration tried to revive the negotiations by enticing Israel with an "incentive package" in return for a 90-day freeze on settlement building.

Before submitting the US offer to his cabinet for a vote, the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, has asked for written assurances that the settlement construction freeze, a precondition for bringing the Palestinians back to the negotiating table, will not include East Jerusalem.

US officials were still trying this week to cobble together wording skirting the Jerusalem issue that would satisfy both Israel and the Palestinians. The chances of reaching an agreement on East Jerusalem, however, appeared more complicated than ever.

The most obvious snag is the referendum law, which complicates any effort to complete a deal in which Israel would cede not only East Jerusalem to the Palestinians but the Golan Heights to Syria. Both areas were annexed by Israel following the 1967 war.

Before passage of the law, any Israeli pullout from areas it occupies, including East Jerusalem, would have had to win the backing not just from Mr Netahyanu's right-wing ministers but from a two-thirds majority of the parliament. Now, if it passes the first hurdle but falls short on the second, it would go to a vote of eligible Israeli voters in a national referendum.

For advocates of a peace accord, a vote by the Israeli public would represent another chance to win approval. Still, the outcome of such a vote also would be uncertain. The vote would no doubt occasion considerable fear-mongering. On the other hand, public opinion polls consistently show that a majority of Israelis support a Palestinian state, though not necessarily one whose capital is East Jerusalem.

Palestinian officials condemned the referendum vote, not least because Mr Netanyahu, whom they distrust, avidly supported it.

"The Israelis want to tell the whole world that they will not withdraw from Jerusalem or the Golan," Mahmoud Abbas, the Palestinian president, said this week at the opening of the new headquarters of the Palestine Liberation Organisation.

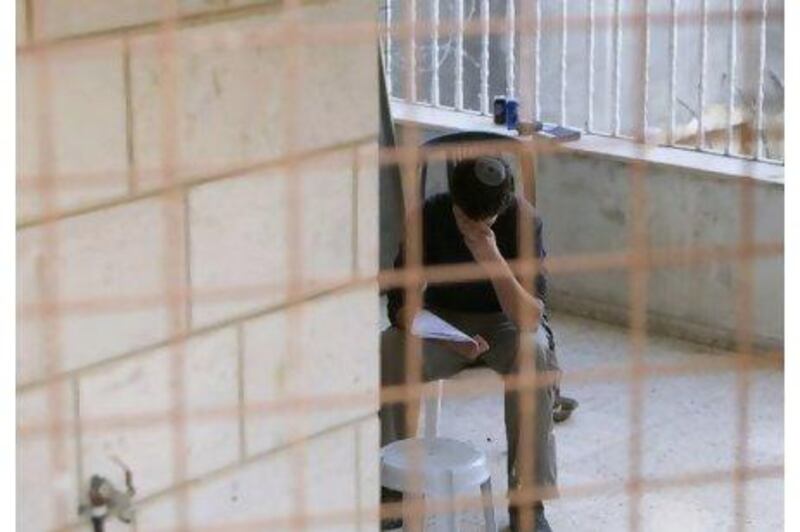

Notably, the new headquarters is located in Ramallah, since Israel has made East Jerusalem off-limits to all Palestinian political activity.

Last month, Salam Fayyad, the Palestinian prime minister, was forced to cancel his appearance at a Jerusalem school after Yitzhak Aharonovitch, the Israeli police minister, issued an injunction against the visit. The school had been refurbished with funds from the Palestinian Authority.

The gaining pace of Israel's encroachment over all of Jerusalem has met with no measurable domestic opposition.

The centrist Kadima party joined Mr Netanyahu's government last month in backing legislation to define all of Jerusalem as a "national priority area". The law would entitle Jews - including settlers - to subsidies and cheap housing if they move to the city.

The legislation is expected to lead to a housing boom, especially in the city's eastern half, where more land is available for development. Since a settlement freeze ended two months ago, Israel has announced plans for more than 1,500 homes in East Jerusalem's settlements.

Most provocatively of all, perhaps, has been Israel's moves on Jerusalem's Old City and its holy places.

This week Mr Netanyahu's government approved £23 million (Dh133m) to give a facelift to the Western Wall, one of the holiest sites in Judaism, and its adjoining plaza. The goal, the Israeli leader said, is to make the area "the focal point and a source of inspiration for millions of visitors and tourists".

Although the Israeli premier did not specify which tourists and visitors he was referring to, it is unlikely he was talking about Muslim and specifically, Palestinian, pilgrims.

Another scheme - also apparently aimed at strengthening Israeli control over Jerusalem's holy sites, including the compound of mosques where al Aqsa is located - calls for tearing down sections of the Old City's ancient walls next to the mosques and building an underground car park and connecting tunnel close by.

Among Israelis, the moves to tighten Israel control over all of Jerusalem have not gone unremarked.

Akiva Eldar, a veteran commentator for the daily Haaretz, called Jerusalem's new status a "deliberate provocation". He also noted that neither Kadima nor the Labor party "would dare to oppose any decision to Judaize - excuse me, strengthen - 'unified Jerusalem, eternal capital of Israel'."

That unwillingness suggests that Israel and the Palestinians could well be hurtling not towards peace talks but towards another round of violent confrontation.

There is more than enough precedent. In 2000, Ariel Sharon, with an escort of more than 1,000 Israeli police officers, visited the Temple Mount complex, site of the Dome of the Rock and al Aqsa Mosque, and declared that the complex would remain under perpetual Israeli control. That declaration helped trigger the second intifadah.