By convicting a Hezbollah operative without asking who ordered him to assassinate Rafik Hariri, an international tribunal in The Hague stuck to political lines that have defined the Middle East over the past 15 years, experts say.

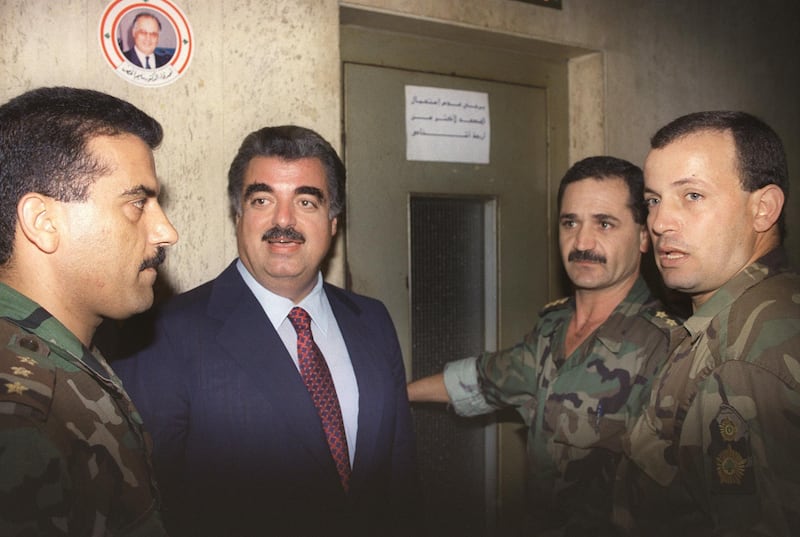

International powers began shaping these parameters not long after the slain statesman was buried in February 2005 in the centre of Beirut, which he was instrumental in rebuilding after the civil war.

Political analysts said it was fairly clear since Syrian regime forces pulled out of Lebanon in April 2005 that there would be no further damage from the assassination to Iran’s regional allies.

France, Germany and Britain did not let the assassination stop them intensifying diplomatic contacts with Iran, which eventually helped to deliver the 2015 nuclear deal.

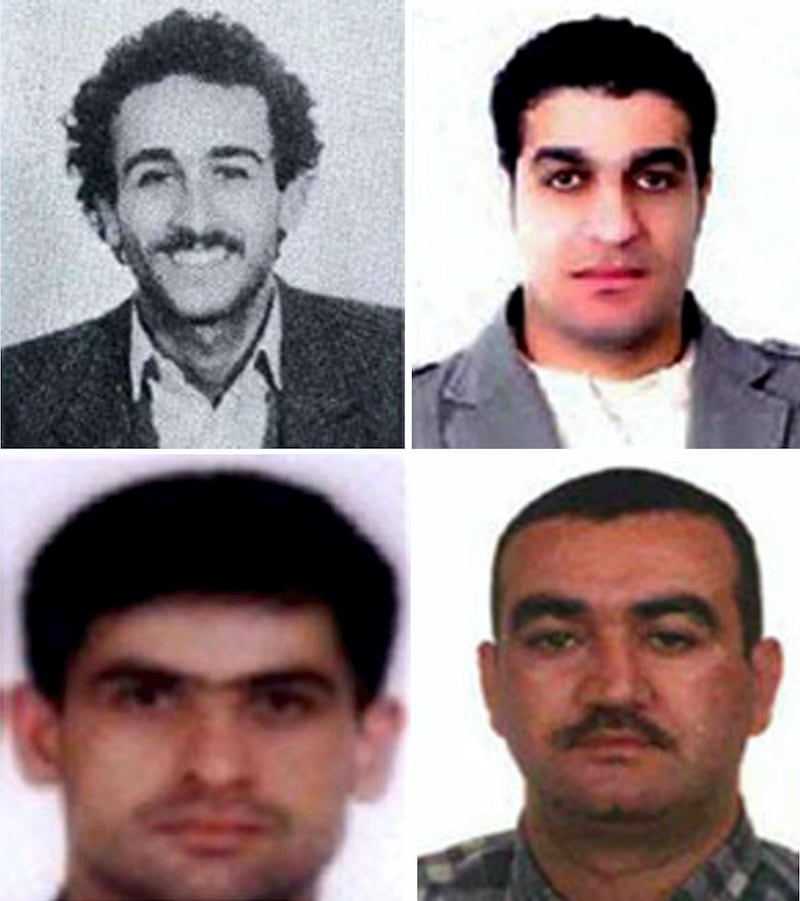

The Special Lebanon Tribunal, the first international court created in pursuit of justice for just one man, convicted Salim Ayyash, the main defendant in the Hariri killing.

Three co-accused were acquitted of all charges.

The tribunal said it found no evidence to link the Syrian government, a main ally of Hezbollah, to the murder, and no “direct evidence” that the leadership of Hezbollah was behind it.

But the tribunal did say there was evidence that Mr Ayyash belonged to Hezbollah.

Prominent lawyer Chibli Mallat, who led international cases against Ariel Sharon and Muammar Qaddafi, said the tribunal had committed a “grave legal error".

Mr Mallat said the judges had “separated the motive from the crime”, although they made it clear that Syrian President Bashar Al Assad and Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah had motives.

"Why were the two not investigated personally before they were proclaimed that they did not bear criminal responsibility all this time?" he asked The National.

Mr Mallat said that even if the tribunal proved Ayyash was a Hezbollah member, then Lebanese authorities must apprehend him, despite the influence the group has on the state.

Hezbollah said that the tribunal's judgment was immaterial to the group, which had refused to hand over the four suspects.

Nadim Shehade, executive director of the Lebanese American University in New York, said the tribunal could not deliver a judgment against a country or an institution or group.

But Mr Shehade said he was confused as to why the judges had wanted to “clarify their position” by announcing a lack of evidence for Hezbollah and Syrian involvement.

“People know that Syria and Hezbollah killed Hariri,” Mr Shehade said. “Those who know, know. Those who deny, deny. And this will not change anybody's mind.”

The Hariri assassination was followed by peaceful street protests, known as the Cedar Revolution, and international pressure, leading to the withdrawal of Syrian regime troops from Lebanon after 29 years.

Lebanese political analyst Youssef Bazzi said the outcome of the investigation was cast when the term of the first UN investigator in the Hariri murder, famed German prosecutor Detlev Mehlis, ended in January 2006.

Mr Bazzi said Mr Mehlis’s successors were more interested in containing the political repercussions than pursuing the case.

“It was becoming obvious that the trail leads to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei in Iran, and no one wanted to go anywhere that far,” he said.

“The whole regional and international construct from the beginning was designed to produce the outcome we saw today."

In 2005, the UN investigators asked to interview Syrian presidential adviser Bouthaina Shaaban.

They wrote to Ms Shaaban for an interview after she hinted that Israel was behind the Hariri assassination.

The investigators wanted to see the evidence that she hinted the Syrian regime had against Israel.

Ms Shaaban never responded, although the Syrian regime was obliged to co-operate with the international investigation under a UN resolution.

In April 2006, Mr Mehlis’s successor Serge Brammertz met Syrian President Bashar Al Assad in Damascus.

Some in the investigations team were astonished that Mr Brammertz did not record the interview, according to a source at the time.

Political commentator Nizar Abdel Qader said that the tribunal’s avoidance of going beyond Ayyash in the Hezbollah command structure “does not mean that Hezbollah does not bear responsibility for the murder".

“This was a political crime par excellence,” Mr Abdel Qader said.

“Justice in such case is not achieved by only going after those who executed the murder.”