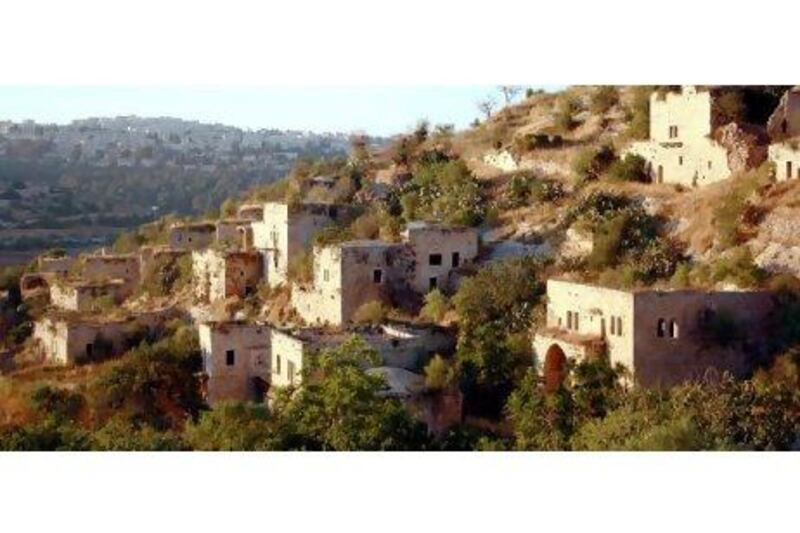

LIFTA, ISRAEL // On a rocky slope dropping steeply away from the busy main road at the entrance to West Jerusalem, a scattering of ancient stone houses cling precariously to terraces hewn from the hillside centuries ago.

The houses are empty and although most Israeli drivers barely notice the buildings, this small ghost town - neglected for the past six decades - is at the centre of a legal battle fuelling nationalist sentiments on both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian divide.

Picking his way through the cluster of 55 surviving houses, their stone walls invaded by weeds and shrubs, Yacoub Odeh, 71, slipped easily into reminiscences about Lifta.

He was only eight years old in January 1948 when, in the early stages of a civil war, the advancing Jewish forces put his family and the 3,000 other Palestinian villagers to flight.

Over the coming months, as Israel was born, they would be joined by 750,000 others exiled in an event that is known by Palestinians as the "nakba" or catastrophe.

Lifta's chief landmarks are still clear to Mr Odeh: the remains of his family's home, an olive press, the village oven, a spring, the mosque, the cemetery and the courtyard where the villagers once congregated.

"Life was wonderful for a small child here," he said, closing his eyes. "We were like one large family. We played in the spring's waters, we picked the delicious strawberries growing next to the pool.

"I can still remember the taste of the bread freshly baked by my mother and coated with olive oil and thyme."

The village has come to symbolise a hope of eventual return for many of the nearly five million Palestinian refugees around the world.

More than 400 other villages seized by Israel were razed during and after the war of 1948 in what historians have described as a systematic plan to make sure the refugees had no homes to return to. A handful of others were redeveloped for habitation by Israeli Jews. Lifta, alone of the deserted villages from 1948, still stands untouched in modern-day Israel.

But now Lifta too is under imminent threat from the bulldozers.

In January, the Israel Lands Authority, a government body responsible for Lifta's lands, announced a plan to build a luxury housing project over the village, including more than 200 apartments, a hotel and shops.

The project, said Meir Margalit, a Jerusalem city councillor, would be targeted at wealthy foreign Jews, mainly from the United States and France.

The developers have promised to incorporate some of the old buildings into the complex, although most observers - including leading architects - say that little of the original village will be recognisable after the project is completed.

Instead, according to Eitan Bronstein, a spokesman for Zochrot, an Israeli group dedicated to teaching Israelis about the nakba, Lifta will suffer the same fate as the hundreds of villages destroyed by Israel decades ago. "The message is that we are finishing what we started in 1948."

Critics have been joined by Shmuel Groag, one of the project's original architects, who has accused the developers of failing to respect the basic rules of conservation in their treatment of Lifta.

Families with roots in Lifta, backed by several Israeli groups, including Rabbis for Human Rights, petitioned the courts to stop the project, saying the site should be preserved in its existing state.

The Jerusalem district court temporarily froze the development in March and is expected to issue a ruling in the coming weeks.

The families have also appealed to Unesco, the United Nations organisation in charge of educational, scientific and cultural matters, to declare Lifta a world heritage site.

The development, however, is backed by the leading conservation bodies in Israel, including the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel and the Council for the Preservation of Historic Sites. The council's director, Isaac Shewky, said the costs of a proper restoration would be "astronomical".

Unlike most of the other 20,000 refugees and their descendants from Lifta, many of whom live in the West Bank and Jordan, Mr Odeh is able to visit his former village because he lives about a 10-minute drive away in East Jerusalem.

Mr Odeh, who offers guided tours of Lifta, has to share the site with many Israeli visitors. Young religious boys have turned the still-functioning village pool into a mikveh, or ritual immersion bath. Other Israelis use the site as a favourite hiking spot. And in the evenings, drug-users take shelter in the homes.

He said he would ultimately like to see the families offered a chance to reclaim their former homes. "We will never forget Lifta. Our dream is to come back."

Few observers expect such a scenario in the current political climate. The Palestinian right of return is widely seen by Israeli Jews as spelling doom for Israel's continued existence as a Jewish state.

"Lifta poses such a threat to Israelis because it offers a starting point for imagining how the right of return might be implemented. It offers a model for the refugees," said Mr Bronstein.