MUSCAT // When Mohammed Al Said started his business, he ran into a quandary.

Mr Said, a UK-trained Omani engineer who founded an oil and gas sector service company, needed to hire technical experts like himself. But government policies required that a number of the employees be Omani.

There should have been plenty of local workers to select.

Official numbers say there are 153,326 unemployed in Oman, and International Monetary Fund has estimates the unemployment rate at more than 20 per cent of the workforce.

But as a recruiter, Mr Said was stumped.

"I ran into the brutal truth that most job seekers are at a high-school level," he said. Among those who hold university degrees, few were willing to take a bet on his new enterprise when more secure government and corporate jobs awaited them. Although roughly half of current high school graduates today pursue high-level education, just 17 per cent of men did so as recently as a decade ago, leaving a legacy of workers with a high school education.

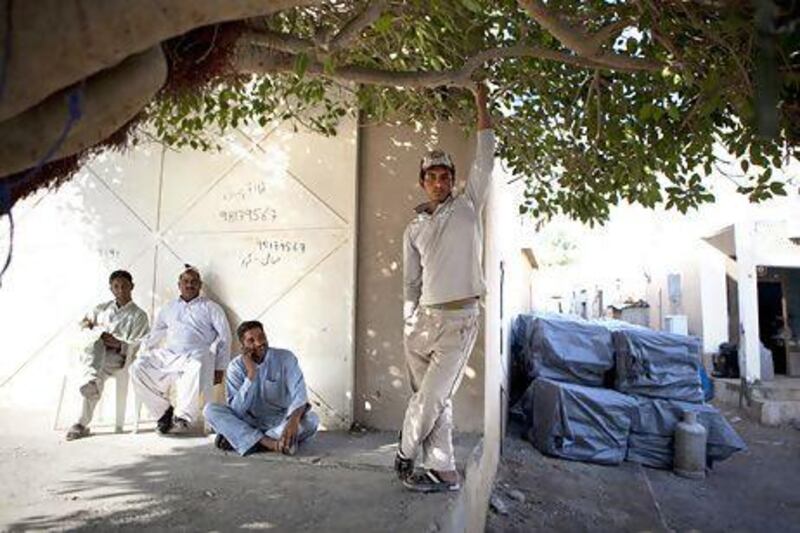

Across Oman, Mr Said's conundrum resonates with employers and the unemployed: many jobseekers don't want the jobs available, and many employers don't want the applicants they find. As a result, the vast majority of private-sector jobs here go to expatriates.

There is a word to describe the disconnect: Omanisation.

But after years of gently pushing Omanis toward the private sector, the country now hopes that entrepreneurs such as Mr Said can innovate their way out of the employment crisis. Which is exactly what he is trying to do.

Mr Said's company is solving its Omanisation problem with a new side business. Mr Said hires underqualified Omanis and puts them into a training programme. Then he returns them to the job market, where other Omani-seeking employers snap them up with Mr Said's three-month money-back guarantee on their skills.

He fills his employment quota, doesn't crowd his company's ranks with inexperienced workers, and earns a fee from the new employer, who pays him for the training.

After mild unrest in the Arab Spring of 2011, getting Omanis into private-sector jobs has become the focal point of state policy — the buzzword in every ministry, the motivation for dozens of new government committees, and the target of a record-high, 12.9 billion rials (Dh123.bn) budget for 2013.

Perhaps the biggest obstacle to reconciling the difference between jobseekers and job options is a widespread preference among Omanis for more secure, higher-paying jobs in the public sector.

At the end of 2012, there were 174,441 Omani workers in the private sector, and 85 per cent of them were earning less than 400 rials (Dh3,820) per month. The salaries were considered low compared with the cost of living in cities such as Muscat, where monthly rents are often several hundred riyal.

"The average Omani would prefer to work in the government than to slog it out in the private sector," said Shawqi Sultan, founder of Oman's only locally-owned surveying firm. He says he has often lost new trainees to government jobs.

Since 2011, the government has already absorbed vast numbers of excess employees into its own ranks. Last year, government spending created 36,000 new jobs and promised to create another 56,000 more - about 40 per cent of which will be in the public sector.

But after decades of growth and now 12 months of frenetic expansion, the government bureaucracy is reaching its saturation point.

"The state, with all its civil, security and military institutions, cannot continue to be the main source of employment, as this calls for a capacity beyond its reach and a mission that the state cannot sustain forever," Sultan Qaboos said in an address to the Council of Oman in November.

Twenty thousand of the new jobs promised this year will be in the military - a sector where Oman already spent 8.5 per cent of its GDP in 2010 than any other peacetime nation except Saudi Arabia, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Civilian sectors are also feeling the strain, says Ali Al Zuwaidi, head of security for the country's civil aviation authority, who has been asked to take 15 new employees into his office since 2011.

"They are bringing them into the system to employ them. But what are they doing in the office? Nothing," he said, adding that they sat idle, some because they were underqualified and others for lack of work to do. "They are absorbing them into the system on paper only."

Cognisant that the bureaucracy is already stretched, the government now wants the private sector to do the rest. It is considering a combination of carrots and sticks to get there.

Like many Arabian Gulf countries, Oman sets quotas of local employees for each industry, ranging from 9 per cent of employees in upper IT management to 100 per cent local employees in clerical accounting roles.

This month, the government also asked departments to review the policies regulating the hiring of foreign workers in an effort to reduce trends towards hiring expatriates. Between January and November last year, 180,000 private-sector jobs went to non-nationals, while 2,500 Omanis left the private sector in the same period.

The government is also looking to give incentives to new businesses, particularly small start-up firms. Next week, the government will host a conference on building small and medium-sized businesses that pundits here expect could help adjust regulations to make it easier to start a company.

"It all starts from education," said Qais Al Khounji, a member of the Education Ministry's new committee on entrepreneurship. "Entrepreneurship has to be taught in schools."

The time is ripe, however. About half of Oman's population is under the age of 20. In late 2011, the IMF estimated that the country would need 45,000 new private-sector jobs each year to absorb the new jobseekers.

"The biggest issue for Oman right now is employment," said Mr Said. "And the engine of any economy is the smaller businesses."

This story has been modified to correct the number of unemployed in Oman