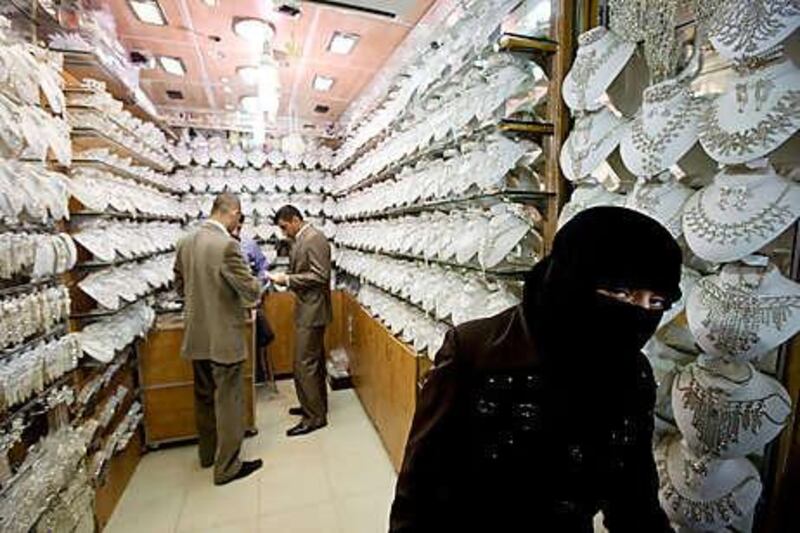

DAMASCUS // The recent ban on fully veiled women from teaching in Syria is the latest move that may signal the authorities are trying to reign in hardline Islamic sentiments. Full-face veils, or niqabs, symbolise a conservatism that, many moderate Muslims and minority groups here say, is not in keeping with local tradition.

Most of Syria's Muslim women wear open-faced headscarves - frequently white - a stark contrast from the all-enveloping black niqab. But the niqab has become increasingly common, particularly in the northern city of Aleppo, fuelling concerns that ultra-conservative interpretations of Islam are spreading. The first clear sign of renewed government action against hardline sentiments came at the end of 2008, when tight new regulations were imposed on private Islamic schools. Those measures were introduced after a deadly bombing in Damascus was traced to a private Islamic institute in the city, one described by a former student as a haven of extremist doctrine.

Another scare for Syria's moderates, minorities and secular groups came last year, in the form of a draft personal status law. It proposed reversing a number of women's and children's rights and paved the way for bringing non-Muslims under Sunni Sharia rulings. Civil society organisations and liberal religious groups, Christian and Islamic alike, were outraged and united against the draft, saying it would "Talibanise" the country. The proposed legislation was scrapped following intervention by the president, Bashar Assad.

The contents of that draft law, civil society activists say, surprised and alarmed the authorities, underlining that ultra-conservative Islam had grown in strength and wielded significant power within the Syrian establishment. Moves were made to reinforce moderate religious sentiments. In January, Mahmoud Abul Huda al Husseini, was appointed to head the office for religious endowment in Aleppo. One of the wealthiest and most powerful Islamic organisations in the country, it has long had a reputation as a bastion of ultra-conservative Islam.

Mr al Husseini, a genial moderniser with degrees in medicine, Islamic law and history, was given a reforming mandate and said his task was to "clean the environment that fosters radicalism". Since taking over the post, he has incurred the wrath of some in Syria's religious hierarchy by stopping dozens of reactionary imams from preaching publicly, on the grounds they had failed to understand Islam's inherent tolerance and needed to learn the Quran properly.

There have been other signals that the space given to hardline Islamic sentiment inside Syria is being newly restricted. Last year, a leaked document revealed the Baath Party, widely assumed to be jealously secular, had approved the opening of a group expounding an ultra-conservative brand of Islam. Run by Sheikh Abdul Hadi al Bani, the organisation contended that television was against Quranic teachings and that women should not be allowed to work outside their home.

According to the memo, the al Bani group was not to be considered a "negative influence" on society if it limited its work to religion and did not dabble in politics. That decision was greeted with dismay by moderates, who said it was proof a blind eye was being turned towards dangerous grass-roots atavism. This year, however, the party reversed its decision on al Bani, saying that, as a secular political organisation, it was opposed to such groups having licence to operate.

Then, without public announcement, came the ministry of education's disputed ban on niqab-wearing teachers, a move the government justified as necessary to defend "secularism". The minister of education, Ali Saad, hinted that other public sector departments would follow suit. Religion is a sensitive topic in Syria, in part because the regime is by background Allawite, a minority sect of Shia Islam, but by instinct secular. It governs over a Sunni Muslim majority population.

In the 1980s, radical Sunnis from the Muslim Brotherhood led a violent uprising against the ruling Arab nationalist Baath Party. The rebellion was crushed and, subsequently, the authorities have taken a hard stance against anything they perceive as domestic extremism. Regular Sunday sessions at the Supreme State Security Court, convened under controversial emergency laws, continue to jail defendants in cases related to radicalism and illegal political movements.

And yet, Damascus has been a major supporter of groups such as Hamas and Hizbollah. The logic behind these alliances is simple: while differing in ideology, they are joined by opposition to Israeli occupation and believe a united front aids their collective cause. Similarly, when the United States invaded Iraq in 2003 and threatened Syria with regime change, Damascus had little incentive to stop guerillas wanting to wage jihad on US troops. Those same militants would, under different circumstances, be Syria's sworn enemies.

As a result, Damascus has for years walked a tightrope of contradiction, siding with Islamic radicals on some foreign policy issues while trying to constrain those same forces domestically. Although there is no question of Syria ending its partnerships with Hamas and Hizbollah while still at war with Israeli, it appears the Syrian authorities may now feel that conservative Islam has been given too free a reign at home and should be hauled back in.

psands@thenational.ae