Ethiopia said it had reached its first-year target for filling a mega-dam on the Blue Nile River and progress had been made on a deal to ease tensions with downstream neighbours Egypt and Sudan.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed's office said on Tuesday the three countries had reached a “major common understanding which paves the way for a breakthrough agreement” and more talks were imminent.

The statement by Mr Ahmed’s office came as new satellite images show the water level in the reservoir behind the nearly completed $4.6 billion Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam is at its highest in at least four years.

Mr Ahmed's office indicated that enough water had accumulated to enable Ethiopia to test the dam's first two turbines – an important milestone on the way towards actually producing energy.

Ethiopia has said the rising water is from heavy rains, and the new statement said that “it has become evident over the past two weeks in the rainy season that the [dam’s] first-year filling is achieved and the dam under construction is already overtopping.”

Ethiopia has said it would begin filling the reservoir of the dam, Africa’s largest, this month even without a deal as the rainy season floods the Blue Nile. But the new statement says the three countries’ leaders have agreed to pursue “further technical discussions on the filling … and proceed to a comprehensive agreement.”

The statement did not give details on Tuesday’s discussions, mediated by current African Union chair and South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, or what had been agreed upon.

But the talks among the country’s leaders showed the critical importance placed on finding a way to resolve tensions over the celebrated Nile River, a lifeline for all involved.

Ethiopia says the colossal dam offers a critical opportunity to pull millions of its nearly 110 million citizens out of poverty and become a major power exporter. Downstream Egypt, which depends on the Nile to supply its farmers and booming population of 100 million with more than 90 per cent of its freshwater, asserts that the dam poses an existential threat.

Negotiators have said key questions remain about how much water Ethiopia will release downstream if a multiyear drought occurs and how the countries will resolve any future disputes. Ethiopia rejects binding arbitration at the final stage.

Egypt and Ethiopia face off over rights to the Nile

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El Sisi stressed Egypt’s “sincere will to continue to achieve progress over the disputed issues,” according to a presidential spokesman. The leaders agreed to “give priority to developing a binding legal commitment regarding the basis for filling and operating the dam”, he said.

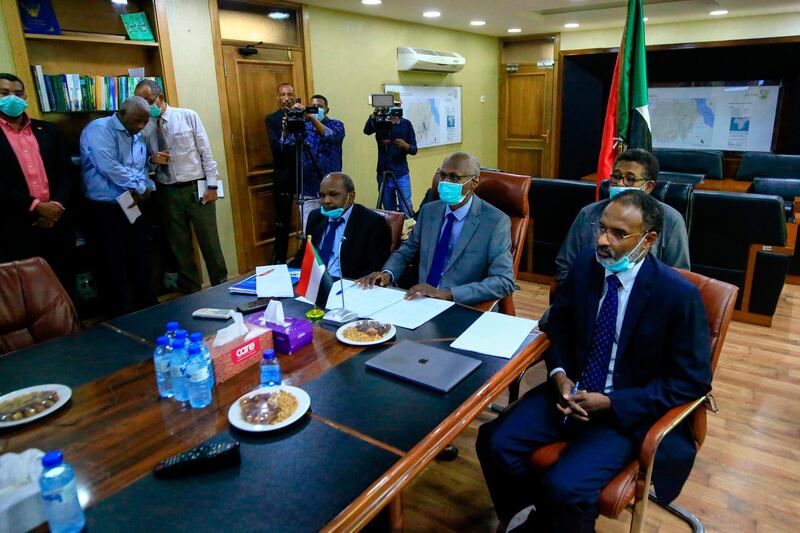

Sudanese Irrigation Minister Yasser Abbas said in Khartoum that once the agreement had been solidified, Ethiopia would retain the right to amend some figures relating to the dam’s operation during drought periods. “Generally, the atmosphere was positive” during the talks, he said.

Mr Abbas said the leaders agreed on Ethiopia’s right to build additional reservoirs and other projects as long as it notified the downstream countries, in line with international law.

“There are other sticking points, but if we agree on this basic principle, the other points will automatically be solved,” he said.

Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and Ethiopia’s leader called Tuesday’s meeting “fruitful.”

“It is absolutely necessary that Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia, with the support of the African Union, come to an agreement that preserves the interest of all parties,” Moussa Faki Mahamat, chairman of the AU Commission, said on Twitter. The Nile “should remain a source of peace”, he said.

Years of talks with a variety of mediators, including the Trump administration, have failed to produce a solution.

Kevin Wheeler, a researcher at the Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford, told the Associated Press last week that fears of any immediate water shortage “are not justified at this stage at all and the escalating rhetoric is more due to changing power dynamics in the region".

However, “if there were a drought over the next several years, that certainly could become a risk,” he said.