CAIRO // Defying predictions that he would step down after nearly three decades in power, the Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak said late last night that he would remain in office to oversee the transtion to elections scheduled for September.

“I will continue to shoulder my responsibilities until September,” Mr Mubarak said in a 17-minute address broadcast over state TV, adding in an apparent reference to the United States and other outsiders who had pressured him to leave: “I have never bent to foreign diktats.”

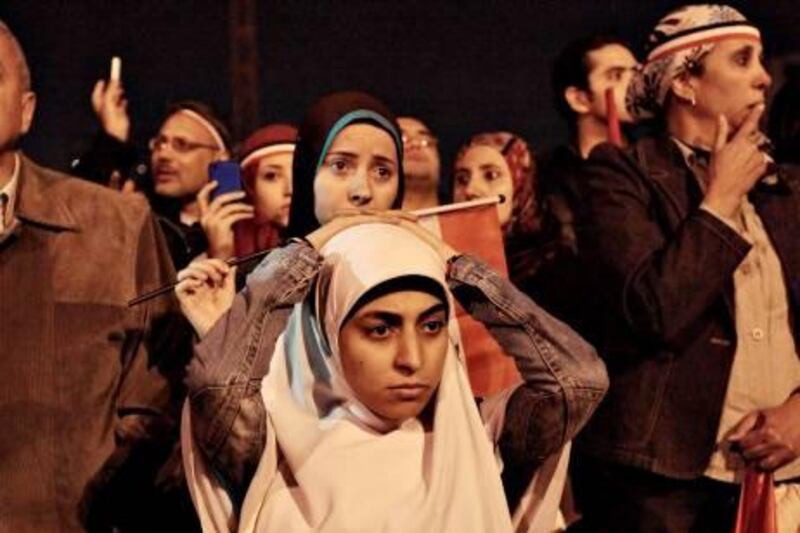

The hundreds of thousands of protesters who gathered in Cairo’s Tahrir Square expecting to celebrate instead erupted in shock, anger and disbelief at the president’s announcement. Many removed their shoes and waved them in the air in a sign of derision towards Mr Mubarak. “Down, Down, Hosni Mubarak” they shouted.

The 82-year-old Egyptian leader had been widely expected to quit. Before he spoke, Wael Ghonim, the Google executive and Dubai resident who became a hero to the anti-regime movement after he was jailed and held blindfolded for 12 days for helping to organise the first protest last month, posted on his Twitter feed: “Revolution 2.0: Mission Accomplished.”

The terms of Mr Mubarak’s transfer of powers to Omar Suleiman, the vice president and former intelligence chief, and the role of Egypt’s powerful military in it were not immediately clear. But the speech left demonstrators deeply disappointed after statements from government and military officials yesterday evening had led them to believe that Mr Mubarak would resign.

____________________________

Egypt's 17 days of unrest

____________________________

The US president, Barack Obama, had no immediate comment on Mr Mubarak’s remarks. Minutes before the Egyptian leader went on the air, however, Mr Obama underscored the momentousness of what was occurring in the Arab world’s most populous country, apparently in the belief that he would make way for new leadership.

“What is absolutely clear is that we are witnessing history unfold. It is a moment of transformation that is taking place because the people of Egypt are calling for change,” Mr Obama said in speech to students in Marquette, Michigan.

America “will continue to do everything we can to support the orderly and genuine transition to democracy in Egypt,” the US president added.

Mr Mubarak’s comments came on the 17th day of nationwide protests that were organised initially with Facebook and Twitter and seemed to come from nowhere. Fearing for their safety, the protest’s young architects, except for Mr Ghonim, have remained in the shadows, unknown to all but a few. Even Egypt’s mainstream opposition leaders have seemed at loss over what to make of them.

Still, the demonstrations they have organised have given voice to many of Egypt’s 80 million people who had grown frustrated with an economy that seemed to favour a few, a political system dominated by a single party and security forces that were viewed as corrupt, capricious and cruel.

Mr Suleiman spoke immediately after Mr Mubarak and called on youth protesters to return to their homes.

"We cannot be driven to the perils of chaos and we cannot allow those perpetrating and plotting intimidation," Mr Suleiman said. "Do not listen to the satellite television stations whose main purpose is to fuel sedition."

My Mubarak vowed to scrap a constitutional amendment passed in 2007 that bolsters the government's judicial powers and would "clear the way for the scrapping of the emergency law one security and stability are restored. The emergency law has been in place for decades and gives the police and security forces wide powers to arrest suspected dissidents and limit the right to free speech and assembly.

Mr Mubarak said he had proposed amendments to five other articles of the constitution governing elections, the nomination of presidential candidates and judicial oversight of the process. He said he would remain in his post until the end of his term in September.

He said: "I am certain that the majority of the people are aware of who Hosni Mubarak is, and I feel pain in my heart from what I hear from some of my countrymen," he said. "I will not separate from the soil until I am buried underneath."

Earlier yesterday, there were abundant hints that Mr Mubarak would step down under the pressure of the protests, a sinking economy and a military that did not want to risk any further loss of its influence came yesterday afternoon.

Army Major General Hassan Roweny told protesters in Tahrir that “everything you want will be realised.”

Later, Hossam Badrawy, secretary-general of the ruling National Democratic Party, said in an interview that he had urged Mr Mubarak in a phone call earlier in the day to leave office “for the good of the nation”.

“This is the only way to restore confidence in Egypt. This is the move that the republic needs,” Mr Badrawy said he told the president.

Soon after Mr Badrawy spoke, the country’s military signalled that it was moving to take control of the country, a further sign that power in Egypt would shift away from the president.

State television showed the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces meeting. Mr Mubarak was notably absent.

The armed forces “have started taking necessary measures to protect the nation and support the legitimate demands of the citizens,” an army spokesman said on state television.

Egypt’s military has produced all four of its presidents since young army officers seized power in a 1952 coup that toppled the monarchy.

Last week, in what was considered a major turning point in the upheaval, the army said it recognised the demands of the protesters as legitimate and said it would not fire on them.

On Tuesday, however, vice-president Omar Suleiman, a former army general and chief of intelligence, made it plain that the patience of the armed forces was wearing thin. He warned that an outright military coup could take place if the demonstrations in Tahrir Square continued.

“We cannot bear this for a long time,” Mr Suleiman told a group of newspaper editors. “There must be an end to this crisis as soon as possible.”

To the surprise of the editors he then warned: “We have two options to resolve this crisis: either dialogue and understanding, or a coup … A coup can be either beneficial or detrimental, but it could lead to further irrational steps and we want to avoid reaching that point.”