Six corpses are lined up under the scorching sun. With a movement of the hand, Dr Mahmoud Hassan, 61, beckons an assistant to open the blue body bag lying at his feet – his aching joints no longer allow him to do it himself.

The whimper of the zipper is followed by a nauseating smell. "This is the last body we exhumed today. She is in a state of extreme decomposition. It's a pile of bones, liquids and gases. It would be impossible to identify her," the Syrian doctor concludes, speaking from the Panorama Park, near the Euphrates river, which snakes to the south of the city of Raqqa.

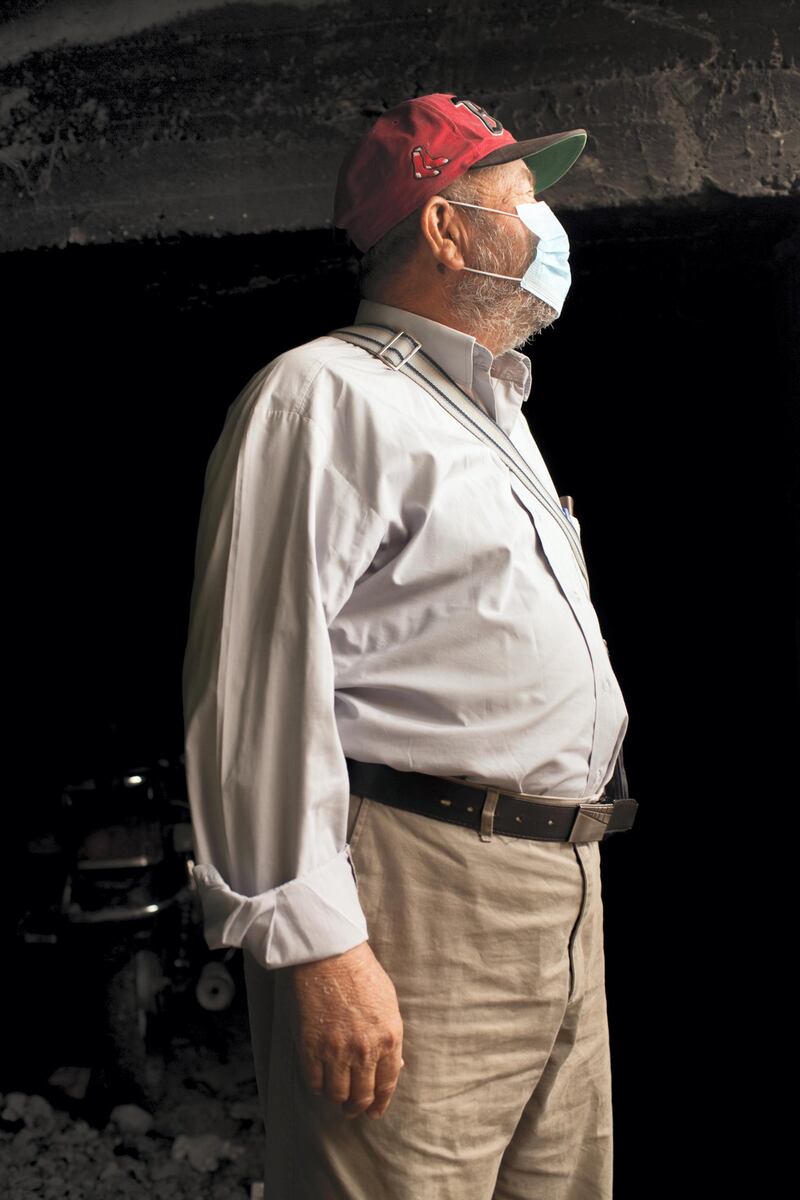

The National travelled to the former ISIS stronghold twice to meet Dr Hassan, who has the burdensome task of being the single coroner in what's known as "the city of death".

During the first interview, in October 2018, Dr Hassan was exhuming half a dozen bodies a day from mass graves or from under the rubble of buildings flattened by coalition airstrikes and artillery rounds. “The dead are in paradise and the living in hell,” he said.

A general practitioner for 34 years, Mahmoud Hassan converted to forensic medicine at the end of the battle against ISIS. It was less by choice than by necessity.

"In such a large city, where thousands of bodies remain, how could we identify them all? We don't even have a lab. All I can do is examine them with the tools I have: my hands, my nose, my eyes,” the rookie coroner said.

“We have made requests to bring in more doctors to help, but nobody wants to do it,” he said. “More than one doctor came here: they saw the situation and they fled."

It took four long months of bloody fighting – from June to October 2017 – for the US-backed, Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) to reclaim Raqqa. While the battle raged and it was too dangerous to go to proper cemeteries, families had to hastily bury their dead where they could, without fear of being shot by a sniper or targeted by an airstrike.

Parks, mosques and schools became improvised cemeteries, the legacy of a ruthless battle in which the international coalition warplanes reduced most of Raqqa to ashes.

Those who can be identified – thanks to jewellery, an ID or a unique physical characteristic – are given back to their families so they can finally bury their loved ones. But like the woman in the bag that day, most bodies will never be given a name, for lack of appropriate equipment, including DNA tests and qualified staff.

The United States has admitted responsibility for the deaths of around 160 residents. The figure is well below the assessments of non-governmental organisations, such as the UK-based monitoring group Airwars and Amnesty International, which estimates that more than 1,600 civilians were killed by the Washington-led coalition.

Around noon, the team members in Panorama Park take off their latex gloves and surgical masks to enjoy a well-deserved break. A worker is using an electric blue mortuary bag as a prayer rug, while the others gather around a fire pit where a teapot is boiling.

A middle-aged man approaches and explains that his brother was buried nearby. “Can you describe him to me?” the assistant asks, taking his notebook. Mohammed Khalawi says his brother was tall, with a scorpion tattoo and Casio watch.

“The tattoo, we won't be able to see it anymore... What about his teeth?” He had long canine teeth and had been shot in the face, leg and maybe in the shoulder, Mr Khalawi adds.

He is told that the team will contact him as soon as they find the missing man but the chances of identifying the body based on this description are low, the medical assistant later admitted.

"Only about 10 or 20 per cent of the bodies are found and returned to their families. It's easier with corpses under the rubble," Dr Hassan says. "When an airstrike targets a house, at least we can assume who the people inside are."

Lack of equipment means his work is more focused on ridding the city of its mass graves than naming the missing. The bodies they can't identify are taken directly to the Tel Bi'a cemetery, in the eastern suburbs, and buried anonymously.

"Such work requires expertise and resources, without which in some cases evidence could be compromised," says Donatella Rovera, Amnesty International's senior crisis response adviser. "The coalition should have provided them with the necessary resources. If there was money for the war, then there should be money for the consequences of the war," she added.

Syria's civil war, a decade of decay

Once his request is submitted, Mohammed Khalawi joins a group of people gathered near a fountain shaped like a flower. He also comes to pick up two other bodies, whose location he knows: Azan, 8, buried in his pyjamas, and his sister, a 4-year-old girl shot in the leg and the face. The children of a friend.

The rain intensifies as the shovels dig into the wet ground. Raindrops trickle on their faces and whip the body bags in a morbid lapping. Mohammed's eyes are dry - the sky is crying for him. The shovel of one of the gravediggers hits a stone. The two children lie beneath. A skull is found first and delicately placed inside a plastic bag. Then some hair, a femur, more hair ... Like gold miners, the rescue team sieve the dirt so as to not forget anything. "We will take them to a real cemetery where they will be near their relatives," Mr Khalawi says.

Every day, more survivors visit the Panorama park in search of those missing. Wahda, 67, is looking for her son Abdullah, who she thinks is buried here but doesn't know where exactly. The cemetery is vast and the number of bodies uncountable.

"The hisba [ISIS morality police] wanted to arrest him. He protested and fought alone against five of them," the old lady whispers. "I think they stabbed him in the stomach, that's what people told me. They handcuffed him, blindfolded him and forced him into a car. That's when an airstrike blew everything up". At the hospital, she was told that her son was taken away by ISIS members to be buried.

She came to the Panorama Park with her six-year-old grandson Omar in the hope of finding him. The orphan is silent. "I want to see a grave with my son's name. I want him to be buried in a real cemetery, so that we know where he is,” the grandmother pleads. “So that his children, when growing up, can say: this is my daddy's grave”. Her wrinkled cheekbones are covered with tears. Her voice is shaking. "I just want to find my son so we can be buried together when I die.”

14 months later, in December 2019, Mahmoud Hassan is at another mass grave. There have been some positive developments in the past year. The doctor was finally joined by a second coroner and they now have a lab, although it still lacks equipment for DNA testing, without which bones stay silent.

In the meantime, they take samples from the bodies they find and store it in their new facility, hoping they will one day be able to match it with DNA records of missing people.

In Salhabiye, 30 minutes’ drive from Raqqa, the doctor and his team recently found yet another burial site – the 31st so far. Most of the corpses found there were beheaded and handcuffed: a strong indication this may be a mass grave for people ISIS had executed.

“It’s harder and harder to identify the new bodies we find, they are increasingly decomposed,” Dr Hassan said. Of the 5,600 bodies unearthed, the team has successfully identified about 700, and they believe 4,000 are yet to be found.

Still, from time to time, a positive identification brings a missing person back to their family and offers the rescue team some solace. Mohammed Khalawi’s brother was eventually identified thanks to his Casio watch and given a proper burial. Unfortunately, Wahda never found her son Abdullah. She fears she will be buried alone, her child forever lost.

The team also hopes to one day identify some of the Western hostages killed or believed to have been killed by ISIS, including American journalist James Foley and Italian priest Paolo Dall'Oglio.

These days, Dr Hassan says he is too old and tired to go on with this colossal task. “I would like to retire next month. I have six grand-children I need to take care off,” he said. “The new coroner is stronger than me, he can take over. I’ll be honest, I have little hope we will ever be able to identify all these people. But it is now time for me to go back to the living.”