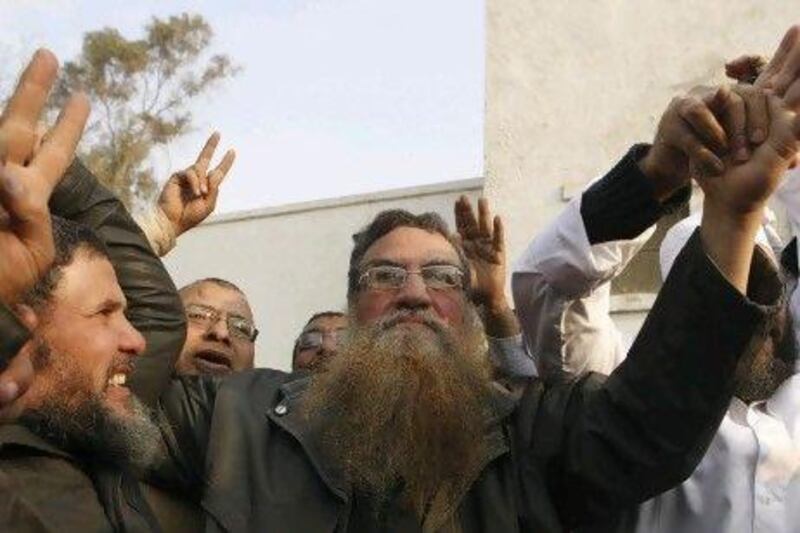

CAIRO // Abboud El Zomor walked out the gates of Tora prison in Cairo in March last year into a vastly different Egypt from the one he had known 30 years earlier.

The country's population had doubled to 83 million and smog now coated the sky. He soon discovered that late at night, the streets of Cairo were crowded with people talking on small devices snuggled next to their ears.

"People are too busy and too worried," Mr El Zomor, 60, said recently. "I hear the ringing of mobile phones everywhere. Sometimes a person will just ring you and hang up, as if to say, 'I remember you'."

Mr El Zomor is just one of the estimated 2,000 Islamists who were released from jail by Egyptian military authorities after the uprising that forced president Hosni Mubarak from power.

His dizzying re-entry into Cairo has been matched by the head-spinning pace with which Islamists have asserted themselves in post-Mubarak Egypt.

Their espousal of violence once earned Islamists official infamy as a mortal threat to the Egyptian state. Now they say they are seeking a peaceful role in the nation's political transition to democratic rule.

In many ways, Mr El Zomor's journey mirrors their path.

In a family member's home on a dusty street in Giza, Mr El Zomor made no secret of his one-time ambition to topple the Egyptian state by force and replace it with an Islamic government.

He readily admitted that, while serving as a lieutenant colonel in the Egyptian military intelligence, he was also a senior member of the clandestine Islamist organisation Gama'a Islamiyya.

Mr El Zomor said he was opposed to the group's eventually successful plot to assassinate the president Anwar Sadat in 1981; not because he thought taking the president's life was immoral, but merely because he thought the timing was bad.

When the assassination plan drawn up by Khaled Islambouli, a fellow military officer and member of Gama'a Islamiya, was disclosed to him by an intermediary, he disapproved.

"I was in charge of creating a plan to overthrow the regime by 1984," Mr El Zomor said. "I refused the assassination plan not because it was wrong, but because it was too soon. We weren't prepared."

The two-minute grenade and assault rifle attack that killed Sadat on October 6, 1981 at an annual military parade brought in decades of brutal repression of Egypt's Islamists.

Mr El Zomor was arrested, convicted of planning to overthrow the Sadat government and sentenced to 25 years in prison.

Regular round-ups of anyone suspected of links to Islamist groups continued in the 1980s and early 1990s throughout Egypt, especially in the Upper Egypt region where support for Gama'a Islamiya has historically been strong.

Later in the decade, foreign powers came to the Mubarak regime's aid. Suspected Islamist militants apprehended abroad were transferred to Egypt by Yemen and Syria, and by the US Central Intelligence Agency in "extraordinary renditions".

Militant Islamist groups fought back, carrying out highly publicised attacks. One of the worst was the Luxor Massacre in 1997, where Islamic extremists killed 62 tourists visiting the Temple of Hatsheput in Luxor.

In 1990, members of Egyptian Islamic Jihad tried to kill Abdel-Halim Moussa, then the interior minister, but killed parliamentary speaker Rifaat El Mahgoub instead.

While the Mubarak government's security and the Islamists fought their shadowy war, Mr El Zomor remained behind bars where, he says, he and other prisoners were regularly tortured and left in small, isolated cells for years at a time.

During his three decades in jail he was held in 10 different locations. His jailers added an additional five years after he refused their demands to, among other things, abandon political activity, support the ruling National Democratic Party and sever ties with other Islamists.

For three of those years one of his fellow prisoners was Ayman Al Zawahiri, who took over as the head of Al Qaeda after Osama bin Laden was killed in May last year.

His worst memory, he said later, was seeing his fellow Islamists marched before a firing squad for their roles in killing Sadat.

Islambouli, who approached the president and threw the grenades that started the attack on that fateful day in 1981, along with three of his conspirators, were in the same cell as Mr El Zomor until the day a prison guard told them to bid farewell. They were executed on April 15, 1982.

"I was living with these people," he said. "When they said goodbye and were taken away, I couldn't stop crying for several days."

In the New Egypt, Mr El Zomor and other members of Gama'a Islamiyya, along with the Muslim Brotherhood, Islamic Jihad and other groups, have taken a different path and embraced peaceful, democratic change.

For him, the rejection of violence by a vast majority of Egypt's Islamist movement - Gama'a Islamiyya officially renounced violence in 1993 - was the result of the maturing of views and intellectual debate during decades in prison cells.

"Every human being grows up and gets more mature over time," Mr El Zomor said. "Our campaign against the regime led the state backwards. They were even more vicious with our members.

"Families were isolated without anyone to support them … the situation was getting worse and, in our reading of Islamic Sharia, we believed it was no longer beneficial to wage jihad by force."

Mr El Zomor hastened to add that peaceful change or not, the goal of Egypt's Islamists remains the same: the establishment of an Egyptian state based on Sharia and the principles of Islam. He said he also wanted to "improve" the ethics of people in Egypt.

He disputed the conventional wisdom that the country has become more religious since he went to jail in 1981.

"People in Egypt have become more religious in appearance but their behaviour is even more westernised," he said.

"There is a love of religion and this was shown in the last elections, but this is not yet about the real practice of religion. Ethics have gone backwards and this is something we must deal with."

But first, Mr El Zomor must deal with a world he barely recognises.

He did not realise that the prayer chants coming from his mobile phone was a "ringtone" and he missed dozens of calls. In a visit to Alexandria, he tried to buy two kilograms of plastic oranges.

"They were beautiful," he said laughing. "I had hardly seen fruit in 30 years."

When Mr El Zomor is not catching up with his family and friends or struggling to come to terms with all that is new on shop shelves, he spends time on a project promoting peaceful relations between Muslims and Christians in Egypt.

His military pension has started paying him a monthly salary and he has a piece of land in Nahya that supplements his income.

Mr El Zomor has not decided what his role will be in the new Egypt.

"I'm still working on what my priorities will be," he said. "I need to think about it more."

Part of that involves pondering on what freedom means with Mubarak gone and after his time in prison.

Watching hundreds of thousands take to the streets last year on a television connected to a satellite dish smuggled into the prison, he said he could see that Islamists were ecstatic about the end of Mubarak's rule.

The high point of those final days was when Habib Al Adly, the minister of interior known as one of the Islamists' greatest nemeses, was arrested and placed in the cell next to Mr El Zomor's.

"I couldn't see him, but the prisoners on the second level could see into both of our cells," El Zomor recalled.

"They congratulated me and gave the victory sign with their hands. When he was taken from his cell, they would pelt him with flip-flops."

In a Friday sermon he delivered during his final days in prison, Mr El Zomor said he declared: "Unfair people must drink from the same cup they served."

"I'm sure he heard it," he said. "I hope so."

Follow

The National

on

[ @TheNationalUAE ]

& Bradley Hope on

[ @bradleyhope ]

This is part two of a three-part series on Islamists Rising in Egypt. Wednesday’s first part - Eight men freed in one more milestone for Egypt’s Islamists and on Friday - The troubled path from violence to peaceful change