The evening sky is morphing from shades of orange to red above the picturesque town of Byblos, and a small, ageing fishing boat with two fishermen slowly rumbles its way out of the ancient harbour.

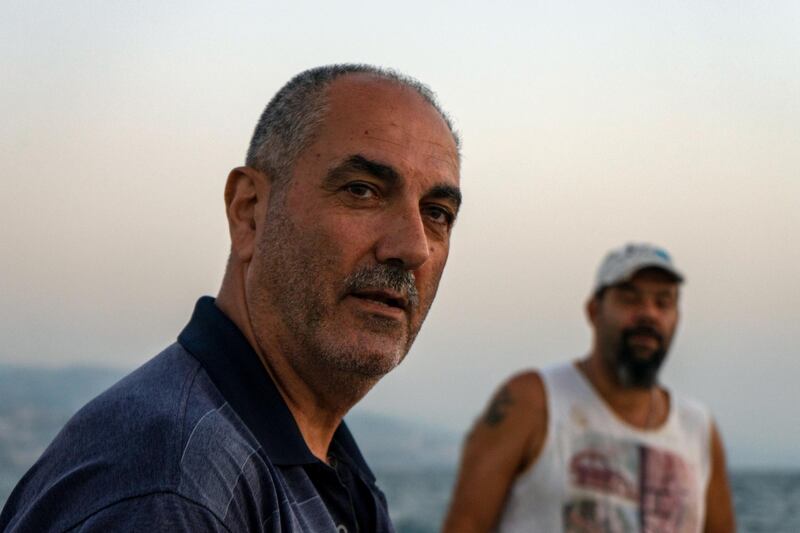

This is the second time today that cousins Philippe Kordahi, 60, and Ziad Kordahi, 45, have been out to fish together. They come from a long lineage of fishermen and have been working the sea since their teenage years, continuing a practice that has sustained communities here for millenia.

This historic livelihood, and those who have dedicated their lives to it, face an existential crisis. The weakened Lebanese Lira, devalued by the country’s crippling financial crisis, has caused prices of supplies to soar while the restaurants they sell to have been forced to close because of the Covid-19 lockdowns.

These circumstances, combined with dwindling fish stocks, have rendered making a living solely from artisanal fishing almost entirely impossible.

The boat slows to a stop a kilometre or so offshore and Ziad begins to unroll the reels of nylon lines that are hooked with 300 pieces of squid to provide the bait.

Over the course of the next hour, he casts lines that are attached to LED-lit polystyrene buoys and empty plastic canisters. He is meticulous, ensuring each hook is attached properly and the lines aren't tangled, a final check to ensure the best chances of a successful catch.

It is hard work, made harder by the economic downturn in Lebanon which has seen prices increase dramatically in recent months.

“A hundred hooks, for example, were 3,000 lira (Dh7) and now we pay 12,000 lira for them. Calamari is 50,000 lira per kilo, we can do three nets with this.

“Before it was 10,000 lira. It is very expensive, everything is more expensive and things are more difficult,” explains Philippe.

And it's not just in Byblos. The National spoke with Rafic Maroun, a fisherman who also owns a small restaurant up the coast in Batroun, who says the situation is similar there.

“Resources are very expensive now, the mazout, the nets and general repairs. We usually buy these in dollars and so prices are up to 12 times more expensive for some supplies. No fisherman can escape these problems,” Mr Maroun explains.

Demand, too, is dwindling. Philippe and Ziad provide red sea bream and other Mediterranean specialties for some of the finest restaurants in Byblos, including the famous Hacienda Pepe. The lockdown brought about by the coronavirus pandemic has meant that tourism, one of the big draws to the ancient town, has all but dried up.

“There was no foreign tourism this summer, just Lebanese visitors. There weren’t any Europeans or people from the Gulf. They used to come here and eat fish and make the restaurants work,” Philippe says.

The red sky has faded to black, and the lines are all cast out to sea, so the engine is turned off and the boat rocks gently with the current. The cousins wait in the hope their cuts of calamari can tempt enough fish for the trip to be worthwhile. As with every trip, there is no way of knowing how much they will catch.

“We can’t know. Before, 20 years, we used to take about 10, 12 or 15 kilos, there used to be a lot of fish. We’ll maybe get 2, 3 or 4 kilos now,” says Philippe.

The problem, he explains, is that people now resort to fishing for themselves, using practices that are harmful to fish stocks.

“There are lots of people fishing now. With the economic crisis, they go down to the sea with cages and take anything. They take the baby fish, and don’t throw them back.”

Destructive fishing practices are a major problem in Lebanon

“Intensive fishing does not allow time for fish to reproduce and regenerate their populations. With the increased imposters in the sector, the lack of enforcement, and the ever-growing economic crisis, some resort to illegal, destructive fishing methods,” Ziad Samaha from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature said.

"This is an extremely short-term profit, as these methods destroy the ecosystem and deplete the fish," he told The National.

Other factors are damaging fish stocks and threatening the livelihoods of fishermen too. “It is important to be aware that there are multiple pressures that are pushing the ecosystem to a catastrophic point. The destruction and privatisation of the coastal line for the building of resorts, marinas and chalets being the most damaging,” Mr Samaha added.

Half an hour passes before it is time to take in the lines. Ziad does this by hand, while Philippe wraps the retrieved nylon around the empty canisters. Most of the hooks are untouched, but occasionally a fish is pulled from the water, unhooked and dropped into a plastic basket.

Once the lines are in, the cousins start making their way back to Byblos. They have caught 32 fish, weighing approximately 2-3 kilos.

“Today we will make maybe 100,000 lira (Dh243). What can I buy with that kind of money for my children?” says Ziad.

“I want to ask the government, how are we supposed to live with the sea? We are the heart and history of Lebanon and we need help, because we can’t continue like this.”

Despite twice-daily fishing trips, both have had to find other work; Ziad for an air-conditioning repairs company while Philippe sells cheese to bakeries in Beirut to make ends meet.

“I know of some fishermen who are working with their wives to make and sell crafts made from rubbish they have found in the sea. We have no reserve funds left to support us. If something goes wrong now, we won’t be able to afford to fix it,” says Mr Maroun in Batroun.

It is just past 9pm, music from the restaurants and voices enjoying the nightlife welcome the fishermen back into Byblos. They moor up, unload the baskets and make sure everything is ready for the next trip in a few hours' time. Despite the seemingly impossible situation, Ziad says he still has some hope. “If you look at what is happening, with the revolution, it has to happen. It is too late for me, but maybe for my children it can make things better.”