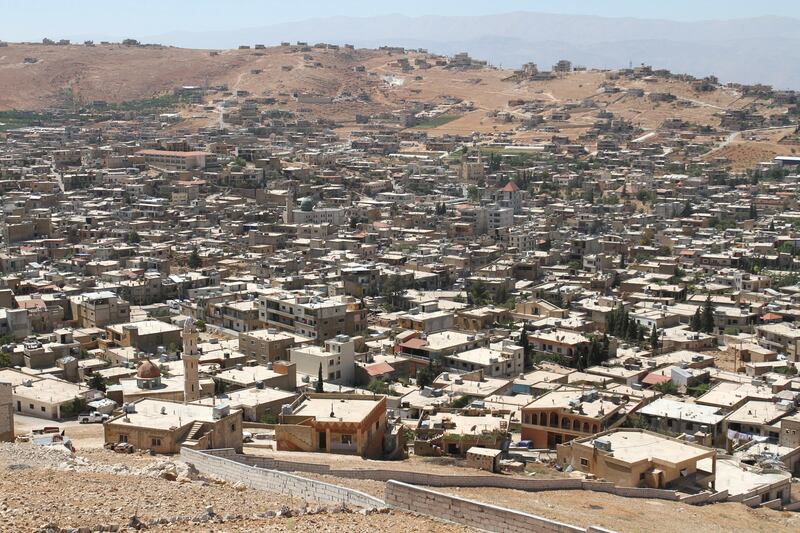

Residents of Arsal are getting a "fresh start" as life returns to normal after the defeat of Al Qaeda-linked militants who had controlled much of the Lebanese city’s rugged outskirts for three years, its mayor said.

Militant group Fatah Tahrir Al Sham — an alliance dominated by the Al Qaeda-linked Jabhat Fatah Al Sham — briefly overran Arsal, only a few kilometres from the Syrian border, in August 2014.

The Lebanese army managed to push the militants back out of the city shortly thereafter, but skirmishes continued until last month when Hizbollah launched an operation that finally dislodged them.

The presence of the militants strangled Arsal’s economy, which is comprised almost entirely of rock quarrying and fruit orchards.

"Arsal has had two wars," Basil Al Hujairi, the city's mayor, told The National. "This is a fresh start for Arsal."

The Lebanese army is now taking over militant positions in the hills that were captured by Hizbollah, which had begun to withdraw from the area, Mr Al Hujairi said.

The defeat of the militants meant that people could return to their stone-cutting factories. Ninety per cent of them have been closed since 2014, he said.

Mr Al Hujairi also confirmed that 3G phone data services were restored in the city last week after being shut down by the army in 2014 to prevent the militants from using it.

________________________

Read more:

[ Despite hardship of living in Lebanon, Syrians don't envy returning refugees ]

[ More Syrian refugees leave Lebanon, but are they heading into the path of air strikes? ]

[ Nearly 8,000 Al Nusra militants, refugees leave Lebanon to Syria ]

________________________

Hizbollah’s defeat of Tahrir Al Sham resulted in negotiations that have so far allowed more than 10,000 refugees to return to Syria, many of them from camps inside Arsal.

The city has a population of about 37,000 Lebanese and at least 40,000 Syrian refugees, many who live in tents inside the city and on its outskirts.

Mr Al Hujairi said he expected further deals to be made with the Syrian government.

“We will facilitate returns for refugees,” he said, before taking a phone call from a Syrian negotiator to discuss what he described as an imminent deal to return hundreds more refugees.

Camps vacated by the returning refugees were being destroyed by the army.

Though thousands of refugees returned to Syria in recent weeks, others refused to participate in the deals and instead moved from the camps on the city’s outskirts into camps in the city.

"Here is better than Syria," said Umm Sherif, who like other refugees who spoke to The National, asked that her full name not be used.

She has two small children with developmental disabilities whom she has been caring for without medical assistance since 2014, when she first arrived in Lebanon.

Umm Sherif and at least 1,300 others moved into the city from Wadi Hammayid, one of the main camps in the area that had been controlled by Tahrir Al Sham.

Abu Mohammed, a father of six, said his family was moved from Wadi Hammayid to Arsal by the Lebanese Red Cross shortly after the Hizbollah offensive began last month.

“A local man provided the buses to move them,” Abu Mohammed said, adding that while women and children were allowed to leave the area almost immediately, men were forced to wait until further negotiations between Hizbollah and militant groups had been completed.

“We camped for 20 days next to a Lebanese army checkpoint” before being allowed to enter the city, he said.

Although life in the camp is difficult, Abu Mohammed said he and other men feared being conscripted by the army if they returned to Syria. He said the Tahrir Al Sham militants had prevented the Red Cross from delivering aid to the camp, and that even bread had to be smuggled inside.

While refugees have been fleeing into Arsal from its outskirts, the city's residents are waiting to venture out to their quarries and orchards.

Among them was Ayman Al Hujairi, the owner of a quarry and stone-cutting factory.

He had managed to make occasional visits to the factory since 2014 but was now awaiting confirmation that the area had been reopened after being retaken by Hizbollah.

“Everything inside my factory was looted or destroyed. It will cost US$40,000 [Dh147,000] to fix all the equipment and buy new things," said Mr Al Hujairi, who is not directly related to the mayor.

“I’m feeling safe, but not normal yet. I will feel it is normal when work starts.”

At his clothing shop in Arsal’s centre, a Syrian man named Abu Adil echoed Mr Al Hujairi’s sentiments.

Despite feeling safer, he said, business had not yet picked up. Abu Adil said that even though he had been running the shop since he arrived from Syria in 2013, he still could not afford to move his family out of the tent they live in.

“The economy is stopped until they open the quarries,” he said.