WADI MUSA, JORDAN // When Ibrahim Bdoul's father, Awad, took a second wife, an Egyptian from Cairo, and brought her to live in Petra almost 30 years ago, it was a shock that took her months to get over. "He told her he owned a big house, but when she found out that it was a cave, she cried each night for three months. She lived there for almost 20 years and she loved it," Ibrahim Bdoul, a 25-year old Bedouin, said.

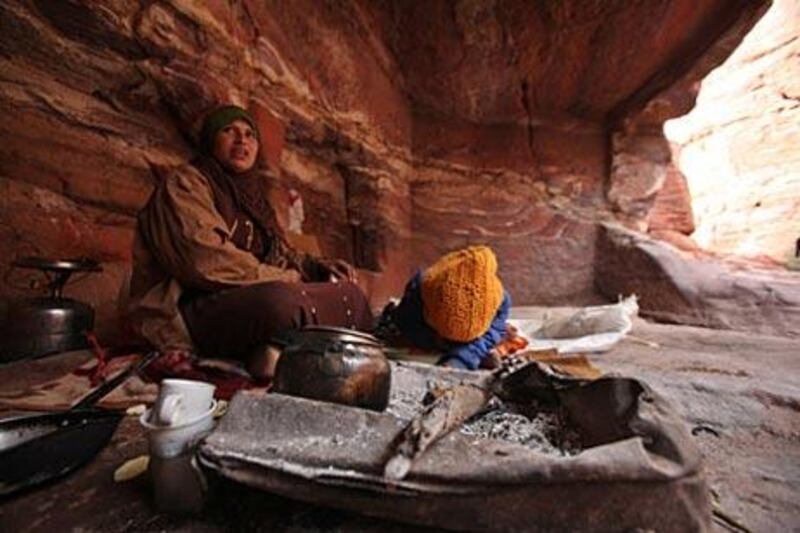

The Bdouls are the largest Bedouin tribe in Wadi Musa, who dwelled in the caves of the ancient rose-red Nabataean city since the middle of the last century. They loved living in their caves. "I grew up in the cave. I used to ride a mule and fetch water for the sheep. Life was simpler then," said Mr Bdoul, who makes a living from renting mules and selling souvenirs for tourists in a tiny shop that the family owns in Petra.

In its efforts to protect the archaeological site, the government forcibly evacuated the caves of most Bdouls in 1984 and provided them with housing in Um Sayhun, a nearby village overlooking Petra. The government promised any male reaching the age of 18 entitlement to a piece of land. But that was when the Bedouins numbered a couple of hundred families. Over the next 26 years, the Bdouls have repeatedly asked the government to make good on its promises so they can build houses, but they say their demands are ignored. About 40 families still live in the caves.

With families growing, most feel squeezed in their two-bedroom apartments. Unofficial estimates place their number at more than 2,500. "We are 10 at home apart from the children. We feel suffocated. We need land. The government has land and it can give it to us," Attalah Abu Saksoukeh Bdoul, 26, who sells silver souvenirs, said. Salman Bdoul, another Bedouin from the same tribe, said he is planning to return to live in the caves. "We live in a tiny apartment. I share one bedroom with my three brothers while my sister and mother sleep in the other," Mr Salman, 30, said. "If I want to get married, I can't think of it. If you want to have a guest at home, you cannot keep him more than 10 minutes. There is no privacy not even when I want to change my clothes. I want to get to back to the caves."

Ibrahim Bdoul still maintains the cave his family used to live in, but it is not his permanent residence. "I keep the cave for fun. I love the wild life. Sometimes I sleep there and I enjoy watching the stars at night. I play the flute there," he said. The cave even has an address. "It is Street No 2, Cave No 1," he joked as he stepped down from his mule. The cave has a wooden door and a lock. Several mattresses and blankets were piled up in the corner. "The problem is that the families are growing and we do not have lands. Petra is all ruins - there are people who want to return to living there," he said.

With their wild unruly hair, and dark eyes marked with strong kohl, the Bdouls add flavour to Petra. Tourism is their bread and butter. Although most are illiterate, they have picked up the languages of the tourists and speak several fluently. During the peak of the tourist season, about 4,000 people visit Petra each day. For its part, Jordan wants to promote the site as a quality destination and wants to protect the archaeological site, which was designated as a Unesco heritage site in 1985, from being overrun. Therefore the government is not keen to see the Bdouls return to their caves. Petra, a once-forgotten city hidden in the mountains until it was rediscovered by a Swiss explorer in 1812, was voted as one of the new seven wonders of the world in 2007.

The sight of school dropouts who sell coloured stones to tourists does not look good on Jordan's record on child labour. Last year, authorities enforced new regulations to make life easier for tourists. They also enforced park rules, such as preventing some silver jewellery vendors from the Bdouls from badgering tourists and ensuring that the donkeys, horses and camels remain confined to certain areas rather than roaming freely as they used to.

There has been talk in governmental circles about relocating the Bdouls in Wadi Araba, almost 150km away from Petra. But such a plan would require the government to secure them with housing and agricultural projects, something to generate a sustainable income. "Even if we want to solve their problem and provide them with lands in the village, it is not a solution. They are too many," Hani Nawafleh, a former member of parliament representing Wadi Musa, said.

"We need to solve their problem at the root level, but successive governments have shelved their case each time. They need to be relocated in an organised manner and have lands that they can plant in order to generate an income that would compensate them for the lost income they make from tourism. "They also need services and military schools to ensure that their children do not drop out. We need to protect Petra, too," he said.

In 1991, many of the Bdouls left their apartments and returned to Petra's caves in protest against the government's reneging on promises to provide them with land. But they returned home after 16 days when the government promised them again to provide solutions, said Atallah Mohammad Bdoul, a 42-year-old Bedouin who sells silver handicrafts near the Great Temple of Petra. Mr Atallah, 42, moved out of his cave in 1984.

At one point, their frustration with the government led to violent clashes. Three Bedouins were killed 10 years ago when the government demolished an unlicensed cave for one of the Bedouins. "We are Jordanian citizens and the government has to provide us with housing. We need services, too. There is population explosion," Atallah Mohammad Bdoul, said. "As a local community, decision-makers should meet with us to address our needs. But they only see the negative things about us. They point to children who beg tourists for money.

"But they don't recall how many times we helped tourists who got lost, or how we returned lost money we found," he said. Nasser Shraideh, chief commissioner of the Petra Development and Tourism Region Authority, said the Bdouls face challenges the authority is trying to address. "We are trying to find the best solution for them based on social and economic studies," he said. Back at his apartment, Ibrahim Bdoul has a desktop computer. Last week he bought a used silver Isuzu pickup from Amman. He enjoys both his lives - in his apartment and at the cave. "I lived all my life here, I will never leave Petra."

smaayeh@thenational.ae