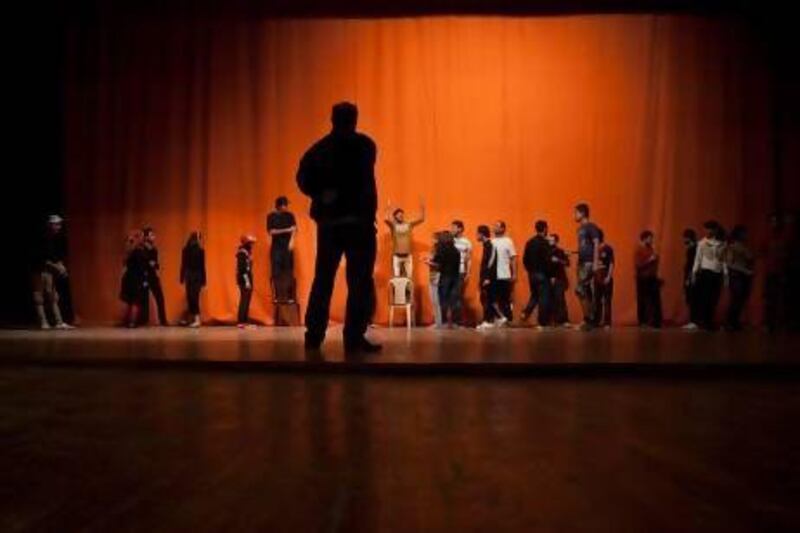

BAGHDAD // The actors run on to the stage, dance in a circle and break into a song that soars to the rafters of the National Theatre of Iraq.

They hold the note on the final line: "Baghdad will still stand", and it rings out over the rows of new, blue seats as they raise their arms to the air. The director shouts his approval and the assorted cast of professionals, amateurs and drama students skips briskly to rehearsing the next number.

Iraqis are proud of their culture, which is rooted in the most ancient human civilisations. Now, with plays, poetry and films germinating again, there are signs the country is recovering not just its life but also its soul, depite persistence violence.

Ten years after the treasures of the National Museum of Iraq were stolen by looters in the post-invasion chaos, five years since an evening performance of a play or concert would be unthinkable because of death squads roaming the city, a year since a spate of killings of people wearing gothic make-up or gelled hair, the situation is unmistakably more relaxed.

In the National Theatre, director Qassim Zeidan says the show being rehearsed is called "I Saw Baghdad".

"Our slogan says there is nothing forbidden in art, we want to explore freedom," he says.

Opening next month, the musical looking at the storied history of Iraq's capital will be performed at night in a theatre recently refurbished with government money. Mr Zeidan sees the revival of theatre in Baghdad as grounds for optimism.

"I want to open a big spotlight, to be against darkness and fill Baghdad with colour and dancing and poetry," says Mr Zeidan, gesturing expansively in a small, dark rehearsal space above the theatre.

Some people share his positive outlook.

"We are able to organise different activities," said Mufidh Al Jaziri, a former culture minister who now heads an association which supports the arts. He helped organise a human rights film festival last year, and hopes to recreate a time in the 1950s when, he says, "Iraq was in the lead in modern poetry, novels and short stories".

And yet, he adds sadly, art and music will not truly grow until the country's politics and security settle into real peace - not just a situation that looks good when compared with the raging civil war of five years ago.

"We need stability, we need a clear picture of where we are going," he says. Blaming the unsettled politics, too, he adds: "It is a disaster to build a country on sectarian things."

And despite the changes for the better in Iraq, there is no need to look far to find cause for concern in a country still deeply and obviously dysfunctional.

Baghdad is still gummed thick with traffic stretching back from military checkpoints, and car bombs and assassinations kill scores every month.

Three years on from the last election, the government has never resolved a stalemate over promises made - and allegedly broken - by Prime Minister Nouri Al Maliki when the Shiite leader cut a deal with the mostly Sunni Iraqiya political bloc so he could stay in power. Arab and Kurdish politicians squabble over land and oil, and citizens complain that little governing actually happens.

In 2003, six months after launching an invasion with the goal of eliminating a security threat in the form of Saddam Hussein, the US president, George W Bush, said that creating democracy in Iraq was also a priority.

"The establishment of a free Iraq at the heart of the Middle East will be a watershed event in the global democratic revolution," he said in a speech, warning that an undemocratic Iraq would embolden terrorists and present a threat to America.

Many Iraqis, however, are now disenchanted with the idea of free elections.

"I prefer no elections, no democracy. Sometimes a tyrant is good," said Ammar Salim, 26, drinking tea in a pool hall with friends from art college.

"We want the government to be powerful - to judge, to punish."

He was cynical about the idea of human rights, saying that they protected criminals.

Mr Salim and his friends voted in the parliamentary elections in 2010 - choosing the incumbent, Mr Al Maliki - but say they will not vote in next's year's poll, seeing no point in doing so.

"Arab history says that multiple parties will fail. It's not succeeding," says Raed Abdulemir, 23, sharing Mr Salim's water pipe.

"Now we have multiple parties which can only last four years. But as Iraqis we need 10 years to get used to somebody."

Iraqis also complain that their feeble governing structure provides inadequate services. Still, this is not quite a society without a state.

Food rations are distributed, millions of people work for the state for salaries much higher than they were under the sanctions-crippled regime of Saddam Hussein, and schools provide free education for children who can now usually get there safely. In Sadriya, a bustling but poor part of Baghdad, the main market road has recently been re-surfaced.

But in the streets behind the main drag in Sadriya, where big families live in small homes under the wood-shuttered eaves of old Baghdadi houses, people say that life is hard.

"I know that Iraq is a very rich country, but they are not taking care of the people," said Niveen Abdelrahman, a 28-year-old housewife whose immaculate house has gold curtains pinned up over cracks in the walls.

Two children play around her as she explains how she encourages them to study but worries that the teachers in Iraq are not good these days. Along with hundreds of thousands of other middle-class professionals, many teachers fled years ago.

The electricity shuts off several times a day, said Mrs Abdelrahman. When it rains, sewage floods the street and seeps into her house. Despite repeated government promises to build millions of homes, there is an acute shortage of affordable housing. As the security situation fluctuates, so do the chances of her husband and father, both forklift drivers, getting work.

Most people blame corruption for the fact that the government's oil revenues, now nearly US$7 billion (Dh25.7bn) a month, do not trickle down to ordinary people.

This month's final report by the Special Inspector for Iraq Reconstruction, a US government accounting watchdog, raised concerns that Iraq is at risk of losing as much as $40bn every year in illegal transfers out of the country.

Despite their inadequate and often corrupt government, Baghdadis are determined to inch their lives toward normality.

In the upscale Zayouna area, the bright lights of Rehana amusement park twinkle into the evening. A little girl wrestles with a stick of candy floss almost as large as she is. Young women with elegant headscarves or teased, uncovered hair stroll along with young men in suit jackets. Families climb aboard the Ferris wheel.

"Our children did not have the fun that other children have," said Samir G Saadi, a civil engineer whose three children cluster round him. "So that's why we are taking them out, challenging the terrorists. Because children must have fun."

In a quieter corner of the park, Wijdan Nabhan, a 20-year-old girl with a crimson-painted pout matching her flouncing hijab, is on a date with Saif Saad, a 25-year-old student.

When extremist groups prowled the streets, they could not have been seen together - not just because they are unmarried but because he is Shiite and he is Sunni.

When pressed, they smile and say they have very different opinions on the war. She lost two uncles and wishes the invasion had never happened, while he says that life under Saddam was a "prison".

But when they come to the amusement park, or to Al Zawra park with its zoo, they prefer to talk about other things: work, study, plans for the future.

"I think that each person is wounded by the situation in Iraq," said Mr Saad. "So we are trying to avoid discussing such things."

afordham@thenational.ae