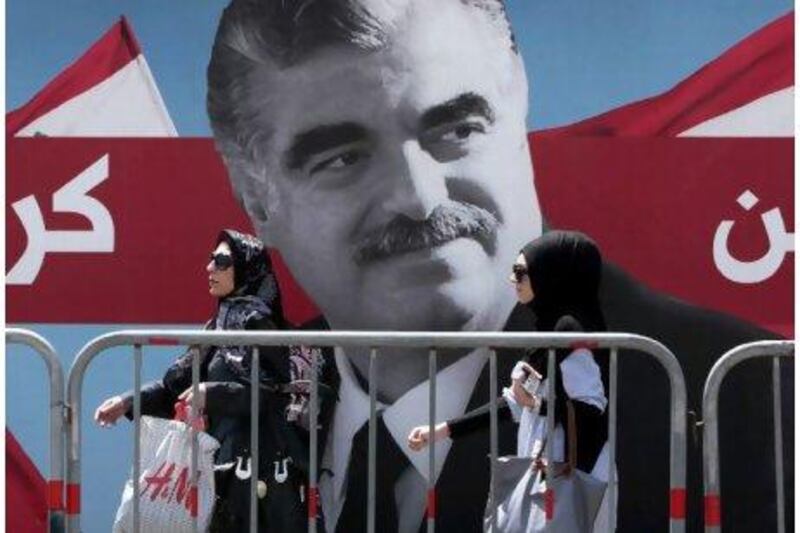

Indictments issued on Thursday against four Lebanese men over the 2005 assassination of former prime minister Rafiq Hariri have shifted the focus of this international murder mystery back to Lebanon.

But whatever transpires there, sooner or later, with or without the suspects actually in custody, the Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL) in The Hague will itself reclaim the limelight as an extraordinary trial is set to get under way.

Even for The Hague, with its abundance of international tribunals and courts, the STL is an odd one.

Its location in the former headquarters of the Dutch intelligence service imbues the probe with an air of cloak and dagger and speaks volumes about the need for extraordinary security.

Just like Lebanon itself, the tribunal and the UN investigation that preceded it are steeped in international intrigue, Byzantine manipulations and conspiracy theories. The probe into the huge explosion in Beirut in 2005 that killed Mr Hariri has been more of a TV whodunit than the probes into the genocides, mass murders and crimes against humanity that the other tribunals in The Hague conduct. And the outcome was often in doubt.

The investigation ordered by the UN Security Council has taken much too long, some critics say. Together with the tribunal, it has gobbled up hundreds of millions of dollars with the 2011 budget alone set at US$65.7 million (Dh241m). It was riddled with leaks and suffered from the attrition of its personnel.

The STL has played a role in the escalating political tension in Lebanon, where the pro-western government of Saad Hariri, the former prime minister and son of Rafiq Hariri, was brought down in January by Hizbollah and its allies. As expected, at least two of its members have been indicted and the other two suspects are believed to have links to Hizbollah.

But most observers do not expect violence in the aftermath.

Hizbollah has become so powerful that it should be able to protect its members from the tribunal through political means. "It does not really need to use violence to prevent cooperation or any effects of the indictment", said Sahar Atrache, an analyst for the International Crisis Group in Lebanon.

It would not be the first time that the tribunal has been hampered by domestic politics in Lebanon, where the pro-Syrian Hizbollah and its allies were opposed from the start. The investigation constantly operated under the shadow of security threats and violence, including the 2008 murder of Wissam Eid, a Lebanese police investigator who unravelled most of the plot.

Even after the tribunal was formed in 2009 and Daniel Bellemare, chief UN investigator at the time, became its prosecutor, observers wondered whether there was enough evidence to issue indictments.

No wonder that registrar Herman von Hebel stressed the extraordinary importance of the moment when the prosecutor finally handed the indictment to the pretrial judge for ratification in January. "This marks the beginning of the stage where judges are involved in the process, rather than only the prosecutor and the investigators," said Mr Von Hebel. The process had not been stillborn.

Not much of that doubt had been in evidence when the UN investigation initially started, just days after the blast that rocked Beirut, killing Mr Hariri and 22 others. The explosion left a huge crater on the main sea road that was kept in place for years to allow investigators to pick over it again and again.

From the outset, the prime suspect was Syria, which had been in conflict with Mr Hariri. Syria maintained a military presence in Lebanon and kept a firm and sometimes violent grip on internal Lebanese issues since the end of the country's civil war in 1990.

The first UN report, delivered just over a month after the murder, set the tone for subsequent investigations. It observed that, "the Government of Syria clearly exerted influence that goes beyond the reasonable exercise of cooperative or neighbourly relations". And it went on to state: "Without prejudice to the results of the investigation, it is obvious that this atmosphere provided the backdrop for the assassination of Mr Hariri."

Habib Nassar, a Lebanese lawyer with the Centre for Transitional Justice in New York, said that considering all the other massacres and murders that had taken place in Lebanon over the years, many could characterise the investigation, called the UN International Independent Investigative Commission (UNIIIC) as "pick and choose justice". It was quickly condemned by some as a political tool for the West and its Lebanese allies to target Syria and pro-Syrian Lebanese parties.

"That does not mean that the crime does not deserve the attention of the international community, and accountability," said Mr Nassar. "Because Lebanon has also suffered a lot from almost systematic political assassination. It has been pervasive, it has been intentionally and systematically used in Lebanon's contemporary history." He also stressed the importance of the tribunal for Lebanon and the region, saying ending impunity was essential.

The issue of legitimacy or credibility has plagued the investigation and the tribunal from the start. Mrs Atrache said that opponents of the investigation would have used any excuse to undermine it regardless of how it had been conducted.

The initial UN report concluded that Lebanon's security services, heavily dominated by Syria, were at the least ineffective during the investigation and possibly obstructed it. Its recommendation that these services be reformed was realised when Lebanese authorities arrested the heads of four security services, an enormous boon to anti-Syrian Lebanese. They were held without charges for almost four years before being released in 2009, on the orders of the STL,

The anti-tribunal camp still claims their detention shows that the investigation has been politicised while its supporters say their release does not prove their innocence but it does demonstrate the tribunal's impartiality.

The arrests were part of the generally expeditious way the UN's first chief investigator, German prosecutor Detlev Mehlis, handled the case.

"There is converging evidence pointing at both Lebanese and Syrian involvement in this terrorist act," Mr Mehlis's initial report concluded in October 2005. In January 2006, Mr Mehlis completed the term he agreed to serve; Belgian prosecutor Serge Brammertz replaced him.

Under Mr Brammertz, the investigation slowed dramatically, to the point where his predecessor and others accused him of dithering. For more than two years, the investigation was perceived to be languishing. After Mr Brammertz was replaced by Mr Bellemare in 2008, Mr Mehlis said in an interview with The Wall Street Journal that during his successor's two-year stint, the investigation, "appears to have lost the momentum it had until January 2006".

But soon after Mr Bellemare took over, the UN Security Council set up the STL and even though many doubts persisted as to whether the evidence was there to indict anyone, the mere presence of a tribunal signalled the determination of the international community to pursue the investigation. Then, last year it became clear that an indictment was being prepared in which Hizbollah members were likely to be charged.

Now four people have been indicted, two of whom are Hizbollah members, senior but not necessarily part of the top leadership of the organisation. No more indictments are before the pretrial judge, Daniel Fransen, at the moment but others may follow by the end of the summer. All this leaves some that are familiar with the probe unconvinced. "Will we get to the bottom of those who ordered the crime? I'm still very sceptical that we will do this," said Lebanese analyst Michael Young, whose column appears in The National. If it turned out that in the end only lower-level operatives were to be charged, "that would obviously raise questions about the investigation".

Even now that Hizbollah members are indicted, the question remains whether anyone significant will be charged.

But even more sensitive is whether the STL will eventually conclude that the assassination was in fact ordered by Syria.

Mr Young believes it must but is insure now whether it will.

"None of the subsequent reports," he noted, "disowned the conclusions of the first Mehlis report, particularly with regard to the motive."