CAIRO // Egypt's ministry of tourism has established a telephone hotline to allow foreign tourists to complain about price discrimination at hotels. The ministry launched the call-in service on July 15 in response to complaints from Gulf Arab visitors, some of whom say they have been quoted higher rates because of their perceived wealth. "There were ample complaints, actually, coming from Arabs in particular," said Omayma Husseini, a spokesperson for the ministry of tourism. "Here in Egypt, they're looked at as the people with the big money, so they used to be charged more than anybody else."

But while the ministry hopes that the new hotline will mollify some of Egypt's most valuable visitors, officials connected to Egypt's hospitality industry said the new hotline is unlikely to receive many answerable complaints. Because room costs at any hotel fluctuate dramatically depending on the type of room, the time of the booking and whether the room has been reserved individually or as part of a group, the perception that one has been cheated by a hotel is often just that, a perception, said Hala El Khatib, the secretary general of the Egyptian Hotel Association, a private organisation that will help investigate complaints.

"This is to help [tourists] feel that we take them seriously. It's not that we're cheating them, you know we're not continuing that, as it might sound. But we have to take their complaints seriously," said Ms Khatib. "I excuse [Arab visitors] for what they think, because if you believe you're being cheated in the hotels, you feel you're being cheated everywhere else." Hotels throughout Egypt are now obliged to display the hotline - which can be reached here on 19654 - at their concierge desks. The call centre, which is open to hotel guests every day from 9am to 9pm, employs a staff of eight people who work in twice daily shifts, Ms Husseini said.

In the two weeks since it began operating, the hotline has received one complaint. Each call is referred to a committee that includes representatives from the hotel association and the tourism ministry. The committee then conducts an investigation that includes a review of hotel invoices and published rates to make sure the quoted price did not deviate too far from the "rack rate" - the highest price a hotel is allowed to charge for a given room.

The tourism ministry already knows the rack rate for each hotel room in Egypt because hotels must submit a rate schedule to the ministry each year as part of standard licensing requirements. If the investigating committee finds evidence of malfeasance on the part of the hotel, it can enforce penalties. A hotel could be ordered to pay the victimised guest five-times the difference between the actual rate and its inflated, discriminatory rate. Ms Khatib's hotel association, meanwhile, is awarded the same penalty as the guest.

In other words, a hotel that has asked a guest to pay US$200 (Dh735) on a room that would have gone for $100 could wind up paying 10 times the difference, or $1,000, in penalties to both the guest and the hotel association. In the most severe or repeated cases, the association can strip a hotel of its licence. That penalty is peanuts compared to the volume of cash handled by Egypt's large, international-class hotels. The real concern for hoteliers, said Marwa Salem, the assistant public relations manager for Cairo's Semiramis Intercontinental, is the hotel's reputation among high-spending Gulf Arabs.

"Why should I, as a hotel, risk my reputation in the market, a very big market, like the Gulf one," said Ms Salem. "You know, word of mouth is the strongest negative publicity ever. So no one wants to play with this [market] segment." Out of the 12.8 million who visited Egypt in 2008, 1.7m came from the Arab world. While that figure is less than Egypt's annual 1.8m Russian hotel guests, the Arab market remains more lucrative because they tend to stay longer and spend more money.

Arabic-speaking visitors from the Middle East and North Africa paid for 22 million hotel nights in 2008 compared with British guests, who only rented 12.45m nights. But higher spending rates are only part of the reason why the hotline targets Arab tourists. Unlike the vast majority of European and American guests, Arabs tend to travel alone or with their families, so they are less likely to reserve rooms through guided tours or travel agencies. Hotels are also more likely to charge individual "walk-ins" with their highest rates regardless of the nationality of the guest, said Ms Khatib.

Arabs also tend to spend more money. Instead of visiting the pyramids and buying souvenir trinkets on guided tours, they purchase expensive gifts and meals, rent cars and visit malls and cinemas. Saudi visitors, in particular, flock to Cairo every summer where they can see the latest film and theatre offerings from around the world - an entertainment that was forbidden in Saudi Arabia until very recently.

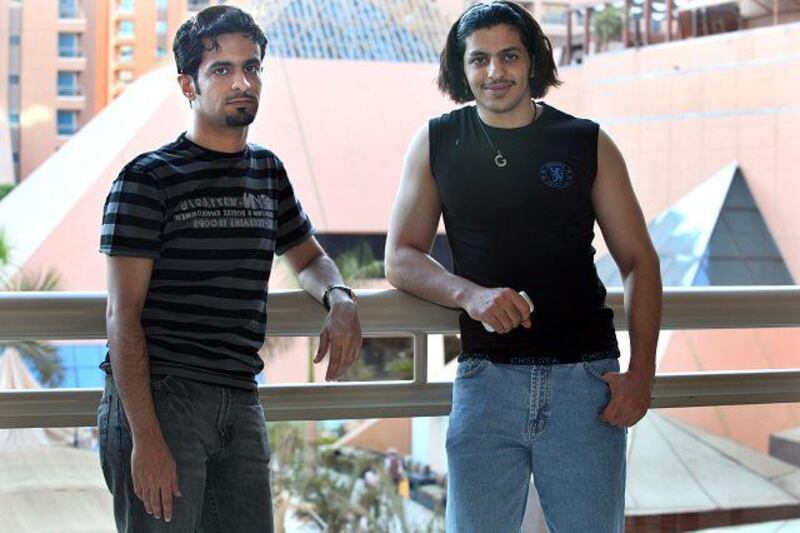

"The pyramids don't change from year to year. We come here for the films. They show the newest movies, and we don't have movies in Saudi Arabia," said Bander al Otaibi, 26, a banker from Riyadh, who was enjoying a fruit drink in the lobby of Cairo's Intercontinental City Stars on Wednesday afternoon. While Mr al Otaibi approved of the ministry's new hotline, he said hotels are the least of his worries when it comes to price discrimination. Taxi drivers, waiters and shop clerks tend to be the most aggressive when it comes to sniffing out big spenders.

"[Egyptians] see my face, and they see a barrel of oil," he said. "If the prices keep rising, maybe I'll just go to Paris instead." mbradley@thenational.ae