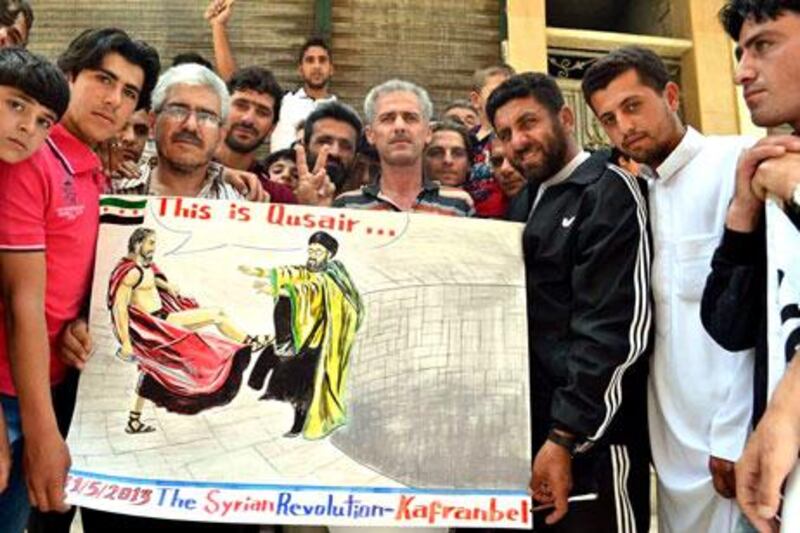

BEIRUT // When Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Hizbollah, took to the airwaves last week to declare his support for Bashar Al Assad's regime, he was taking one of the biggest gambles in the Shiite militant group's 28-year history.

While it never shook its status as an enemy of the West, Hizbollah had commanded respect across the Arab world for its passionate resistance to Israeli aggression. That support crossed sectarian divisions between Sunnis and Shiites, but by supporting Mr Al Assad's regime Hizbollah runs the risk of alienating itself, say analysts.

"In the short-term, Hizbollah won't have a decisive impact on the Syrian conflict," said Frank Wisner, a former US ambassador to Egypt. "But in the medium- to long-term, it's really lousy news for Hizbollah. They are inflaming tensions between Sunni and Shia. Public opinion of them in Lebanon is shifting. It could lead to a major weakening for them."

Mr Nasrallah claimed in a speech last Saturday that some in the Syrian opposition were part of a US, European and Israeli plot that threatened Lebanon,

He called Syria the "backbone of the resistance" against Israel and confirmed that his fighters were in Syria, something long suspected after funerals in Lebanon for Hizbollah "martyrs" increased in recent months.

"We will continue along the road, bear the responsibilities and the sacrifices. This battle is ours, and I promise you victory," he said, addressing his supporters during a Liberation Day ceremony, the 13th anniversary of Israel's withdrawal from south Lebanon. He cast Hizbollah's war as being with the "takfiris", a phrase used to describe ultraconservative Islamist groups - some affiliated with Al Qaeda - which are fighting as part of the Syrian opposition.

The risks in this foray are manifold. Most seriously, it could precipitate more sectarian clashes in Lebanon and broaden the already growing tensions between Shiites and Sunnis across the Middle East.

With its fragile balance of power between sects, Lebanon is a "crucible in which all the dynamics and schisms and fissures of the region are reflected", said Alastair Crooke, a former veteran British intelligence officer who now runs an NGO called the Conflicts Forum that seeks to deepen the understanding of Islamic movements in the Middle East.

"The conflict has already spilt into Lebanon," he said, referring to rocket attacks last week in south Beirut and fighting that has raged in the northern city of Tripoli for more than a year. "But at the moment, it hasn't spread in a way that is beyond containment."

Gen Salim Idris, the chief of staff of the Free Syrian Army, has already warned that rebels would "pursue Hizbollah to hell" if they did not cease their activity in Syria. Hizbollah's military escalation has also thrown a wrench into plans for a new peace conference in Geneva, with the Syrian National Coalition saying on Thursday that it will not participate unless Hizbollah militants withdraw.

What is more, Hizbollah's own power is on the line. Its move into Syria is unpopular in Lebanon, with Sunni and Christian groups quietly fuming at the group's decision to drag the country into a conflict they would rather stay out of. Mr Nasrallah's speech only confirmed that Hizbollah is a state-within-a-state, masquerading as a political party but making decisions that affect the country without any consultation with other factions.

Even the Shiite community in Lebanon is seeing some divisions about Hizbollah's recent activity, said Yezid Sayigh, a senior associate the Carnegie Middle East Centre in Beirut.

"I don't think [Hizbollah] are in a comfortable position," he said. "They are convincing themselves of what they are saying, but it's not clear that everyone in the rank and file agree, even if they accept the basic argument" that Syria is a crucial part of the "axis of resistance" against Israel, along with Iran.

If Mr Al Assad's regime collapses, a new rebel-led government would rise in clear opposition to Hizbollah. At the very least, it would seek to repay its backers in the West by helping shut off Hizbollah's arms pipeline and leave the group isolated from its backers in Tehran.

Even if Mr Al Assad were able to hold on to power through a political agreement - something highly unlikely at this point - there are no guarantees that Hizbollah would not be sacrificed as part of any bargain down the road.

"It's always the smaller groups that get cut out of a deal," said a Sunni politician in Beirut. "They are putting a lot on the line with this escalation."

The situation is a far cry from 2006, when Hizbollah was heralded for its courage by Sunni and Shiite alike after forcing an Israeli retreat from Lebanon.

"A lot of Sunnis were really proud of Hizbollah in 2006 for standing up to Israel," said Timur Goksel, a former political adviser to United Nations peacekeepers in Lebanon. "Now those days are gone. The escalation in Syria shows that they see this as an existential struggle, no matter the risks."

bhope@thenational.ae