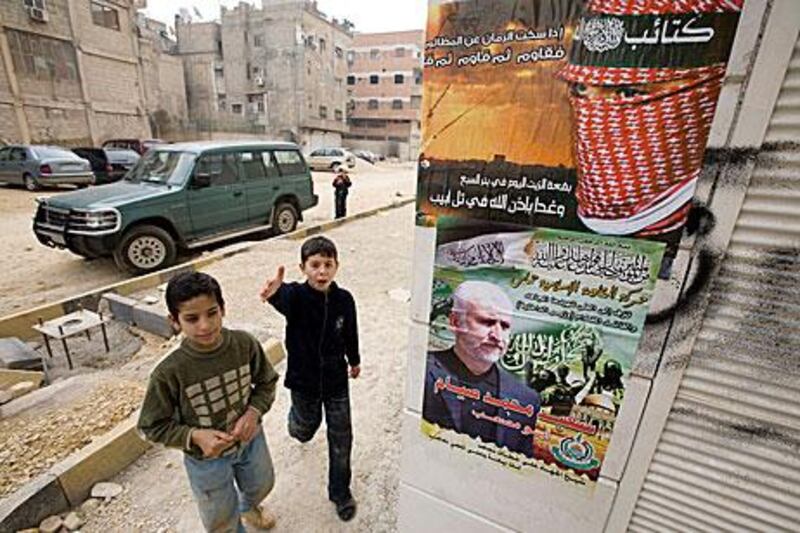

WASHINGTON // The Syrian exile lasted more than a decade. But as the country descends further into violent chaos and relations with Damascus grow strained, Hamas's time in the city is coming to an end.

Hamas reduces presence in Damascus

While maintaining a nominal presence in Damascus, Hamas was also seeking a new location for its headquarters. Read article

Editorial: An opportunity as Hamas comes in from the cold. Read article

Hamas premier leaves Gaza Strip for first time since 2007. Read article

Casting about for a new base, however, the Islamic Resistance Movement is finding that for now at least, there are few available options.

This is ironic, since Islamist parties are emerging in countries where popular uprisings have brushed ruling regimes aside.

Consequently, Hamas would appear to have been strengthened by the region's turmoil. Certainly, the number of potential allies for the movement has greatly expanded.

But for now, with their energies focused on domestic concerns, none are coming to its aid.

So, as reported in The National yesterday, it continues to reduce its presence in Damascus with no certainty about where it might relocate its headquarters. Any move out of Damascus would unquestionably be a blow to the movement. The Syrian capital has been a crucial bastion of support for Hamas over the years.

But the violent crackdown by Bashar Al Assad's regime has left Hamas in a difficult position.

On the one hand, Hamas has enjoyed protection, support and stability in Damascus, the self-styled capital of the Arab resistance, for more than a decade. It is partly for this reason that Hamas leaders are loath to distance themselves publicly from the government in Damascus. Reports its leadership-in-exile is upping sticks have therefore been officially denied.

On the other hand, Hamas has always presented itself to its domestic audience as the party of reform and justice, to set it apart from Fatah.

Cleaning up and democratising Palestinian politics was the platform that saw Hamas win parliamentary elections in 2006.

Mr Al Assad has rejected opposition calls for similar reforms in Syria and even, reportedly, a direct plea from Khaled Meshaal, the Hamas leader, which apparently precipitated a falling-out between the men.

Hamas, a Sunni Islamist movement that gained much of its political authority from democratic elections, cannot be seen to be condoning an Alawite minority's violent crackdown on a majority Sunni population demanding the same democratic rights.

A break with Damascus will also have repercussions for relations with Iran, even if the significance and closeness of that relationship has usually been exaggerated.

The risk for Hamas is that it now faces losing two sources of material and political support.

Other countries have already reportedly stepped in with offers to host Hamas, however.

Qatar has steadily improved its relations with the movement in the past few years, but is geographically far away from the Levant. There is a suggestion that Jordan may take some Hamas officials back, though Amman is unlikely to want to resume hosting the entire leadership as it did before 1999.

Intriguingly, Turkey has also emerged as a possible destination, a relationship both sides are likely to want to explore.

Ankara will be keen to deepen its growing influence with all players in the region, while Hamas will want to take advantage of any flourishing relationship with a Nato member and regional powerhouse.

In the long run, however, Cairo seems a more natural fit. Egypt controls access to and from Gaza and its peace treaty with Israel affords Cairo a unique mediating role.

Moreover, Egypt's Muslim Brotherhood is emerging as the main political force in the country and ties will inevitably grow closer. This, however, will take time while Egypt settles down. Indeed, while many pieces are falling broadly in a favourable direction for Hamas, the movement will have to ride out a period of uncertainty before new regional alignments solidify.

In the meantime, as it searches for a safe harbour in choppy seas, Hamas will seek to keep the situation with Israel calm while it devotes its energies to improving ties with Fatah and shoring up its political base in the Palestinian territories, as well as its membership in the Palestine Liberation Organisation.

Like all political movements, political parties and governments in the region, Hamas is struggling at the moment to see what is around the bend. Unlike others, however, it can perhaps feel a little less fearful about what lies ahead.