TEHRAN // Sami, in his early twenties, is typical of Iran's post revolution youth: frustrated by social restrictions but a staunch defender of his country. Yes, he admits, Iran has economic problems, but so does the rest of the world. Yes, the Revolutionary Guards do play a prominent role in public life, "just like the British army do". But, he sighs: "I just wish it was easier to socialise with girls."

There are about 49 million Iranians, or 70 per cent of the population, who were born after the revolution in 1979. As youth unemployment soars to 35 per cent and a conservative government clamps down further on already limited freedoms, some outsiders have warned of growing resentment among youth eager to lead a more liberal lifestyle. In fact, a recent Brookings Institution report called Iran's youth "a foreign policy opportunity" for the US and its allies who are keen to support opponents of the country's religious hardliners.

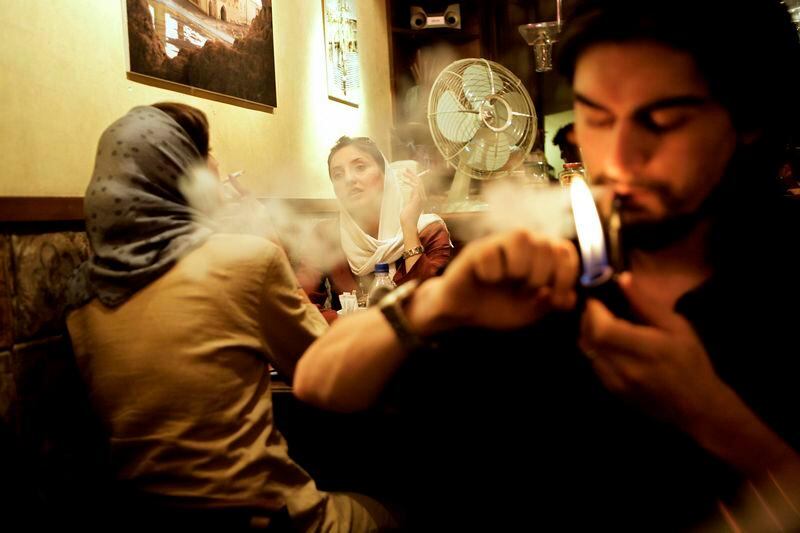

Although you do not have to scratch very deep to find frustration at the public, cultural and social limitations, look a little deeper and it seems many of Iran's urban youth have found their own way of circumventing the system. Most foreign films, books and magazines are banned in Iran, but pirate DVDs, illicit satellites and the internet still offer a window to what is happening in other countries.

Under Iran's strict Islamic law, men and women are banned from socialising with unrelated members of the opposite sex. Although in practice, it is not unusual to see men and women together, there are no venues for them to mingle. So the young have taken to using cars to cruise the streets in search of new friends. After about 8pm in Fereshteh, an upmarket area in north Tehran, young men, usually in pairs, will drive around the streets looking for a corresponding brace of girls who will, after several laps, stop to exchange phone numbers.

Conscious of the watchful eye of the religious police, the men and women check each other out through the car windows in a stop-start fashion until an opportunity presents itself to make contact. It brings traffic to a standstill at weekends, and is not the most romantic of courtship rituals. "The boys' attitude is not important, it's the make of car," said one young man, "and who's willing to stick it out to the end. That's when you get all the girls' phone numbers."

Taking risks has always been a characteristic of the young, and Iran's youth are no different. Although the drinking and selling of alcohol has been banned since the revolution, Tehran's party scene is legendary. "You can do anything you like in Iran," said one young woman from a wealthy family, as her friend poured out shots of vodka. But there is a cost of course: you need a house and money. Real estate prices have skyrocketed in Iran in recent years, meaning that 70 per cent of men and 50 per cent of women in their 20s now live with their parents, compared to 50 per cent and 20 per cent respectively in the mid-1980s. The absence of social distractions though does mean that young Iranians pursue their passions with a rare dedication and focus.

"From the second I come home from college to the second I go to sleep, I'm designing," said Khushe, a petite 21-year-old civil engineering student with a sideline in handmade manteaux (the knee-length garment women are required to wear over trousers). Her new spring collection is so chic it is hard to think of it as Islamic dress. Cinched waists, lace-trimmed pockets, asymmetrical collars; the details on each garment are carried off with flair and confidence. A completely self-taught designer, she has already sold 100 garments at between US$70 (Dh260) and $250 each. But making money is not the point of her enterprise.

"I don't want my clothes to be on everyone's back," she said, "I want to express myself." Shaheen, a mechanical engineer in his early 20s, is also self-taught, but in producing hip hop. "I downloaded files from the University of Berkeley," he said. "Some resources I found online, others I asked for." In his friend's private studio, they produce rap records which are distributed on the internet. Although not technically illegal, their work is still considered underground as they do not have official permission.

Sahand, the founding member of the Rap Larzeh collective, which has 14,000 fans on MySpace, typifies the kind of contradictions in Iranian youth which make it difficult to see them as a "foreign policy opportunity". Educated in California and eloquent on the subjects of Tupac and The Roots, he nonetheless displays a deeply felt nationalism. "I go to the mosque. If there was a war tomorrow we'd all fight for our country."

On the walls outside his private studio hang portraits of the ancient Persian king, Cyrus, and the Imam Ali (few young Iranians self-identify as atheists or even secularists). Sahand's lyrics would make the Brookings Institution blanch: "Stand up, fight for your country," he raps in Jang, or War. "They're telling us we're building bombs, but they're using bombs." Rap Larzeh's output blends American beats with traditional Iranian instruments like the santoor and the tar.

All the crew have day jobs as Ershad, the ministry of culture and Islamic guidance, has not cleared any of their records for sale in Iran. Like many of forms of expression, "you need money to rap in Iran," Sahand said. But for some, the only affordable option of escape is the descent into drugs. Situated next to the poppy fields of Afghanistan, Iran is on one of the world's busiest drug trafficking routes, and the problem has exploded in recent years. According to the UN, three million Iranians are "problematic" users of opium derivatives.

In a Tehran drug clinic, Morteza, now 35, recalls how he first became addicted in his early 20s. "There was no fun and entertainment," he said. "I realise how important that is now, and I take my son to gymnastics classes." Like people everywhere, Iranian youth make their own personal accommodations with their circumstances, with the government, with the restrictions they live under, and live the best lives they can in the spaces available.

"In some ways, I've got a great life," says Ali, a modern languages student. "I study, I've got a girlfriend, a car, my family are all healthy. But this thing," he puts up an index finger as if testing the direction of the wind, "affects everything". If change does come, however, it will be on Iranian terms. * The National