CAIRO // When it comes to the political turmoil in Egypt, Gamal Al Banna is anything but short-sighted.

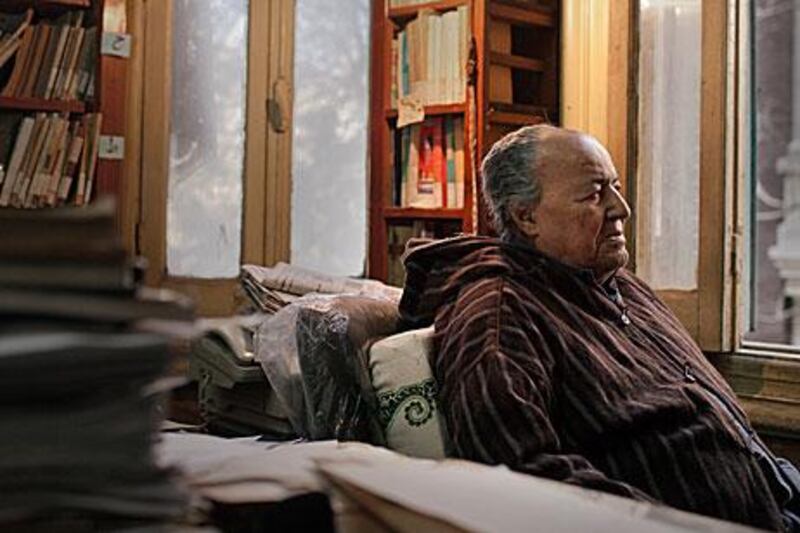

Indeed, the 91-year-old younger brother of the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood sees developments through the lens of the 30,000 volumes of Islamic theory and world history that line the walls of his office near Bab Al Sheariya Square in downtown Cairo.

Looking elfin in a Moroccan hood and scarf behind a desk stacked with paper, he said the success of Islamist groups in parliamentary elections - the Muslim Brotherhood-backed Freedom and Justice Party won roughly 45 per cent of the seats in the lower house - was but a blip in Egyptian history.

"I'm completely unhappy with their victory, but it is not a major historic moment," he said dismissively. "They are living in a different time than our contemporary one. I think they will fail to deliver a better society."

That repudiation of the movement and ideology that Hassan Al Banna built into one of the most powerful organisations in the Arab world does not mean he has any less respect for his brother, who was assassinated in 1949. Gamal describes Hassan as a "genius", comparing him to Vladimir Lenin, who spread communism across the world, and John Rockefeller, the American businessman who built up an oil empire and spread capitalism.

Still, Gamal has devoted his life to a cause far different than his sibling's - a liberal interpretation of the Quran that eschews religious institutions and Islamic political movements.

His interpretations, part of what he calls the Islamic Renaissance, have led him to declare that a Muslim woman does not have to wear a hijab and can lead fellow Muslims in prayer, and that many of the Hadiths are inconsistent with the Quran. His controversial opinions have made him an outsider in Islamic scholar circles, including the state-run Al Azhar University and of course, the Muslim Brotherhood itself.

His criticism of these institutions and groups is rooted in a belief that Islam has veered off course from what he calls its true nature. In his view, it has become an end in itself instead of serving as a guide for Muslims on how to live their lives.

The result is that many modern Islamist groups are misogynist, illiberal and seek to circumscribe freedom of thought, rather than allow Islam to be continuously reinterpreted to mirror the realities, innovations and challenges of modern life, he said.

He derides such ultraconservative moves as the recent court case against Coptic Christian business tycoon Naguib Sawiris for publishing a cartoon of Mickey and Minnie Mouse.

"They are very sensitive about anything about their religion, but what is the criticism?" he asked, speaking in both Arabic and English. "What is the problem?"

He reserves some of his most incisive criticism, though, for the Salafis, a branch of Islam that calls for Muslims to style themselves around the 7th century world-view into which the Prophet Mohammed was born. The Salafis' whose political party won 20 per cent of the seats in the lower house of parliament. But these strict interpreters of the Quran are not following the true path of Islam, Mr Al Banna said.

"They don't live in the present age," he said. "They focus too much on individuals from the past. They are not real Muslims. They are more like an offshoot, like the Sufis."

Mr Al Banna credits his life's work to an upbringing that was religious but not dogmatic.

While his brother Hassan was mobilising young men to resist the regime, his father Ahmad, who repaired watches for a living, spent more than three decades collecting and interpreting the 30,000 sayings of Imam Ahmed Ibn Hanbal, founder of one of the four main streams of Sunni Islam, in 22 volumes. His father also admired classical literature, reflecting his view that religion did not reject the secular arts.

Gamal Al Banna believes his strength stems from a willingness to debate controversial issues and the refusal to follow the views of others. This is the driving force of his interpretation of the Quran, which he says should be a liberating force rather than a constraining one. Thus, women should be treated as equals and people of other religions allowed to coexist peacefully.

Fawzia, his sister, made his life of scholarship possible through a donation to his foundation and an inheritance she later left him when she died in 1997. He lives in a small bedroom at the back of his office and spends most of his waking hours devouring as many as two books a day. Unbeholden to any institution or movement, he said he feels "free" to devise his own interpretations with Allah as his guide.

For instance, he rejects the idea that the government should base laws on interpretations of Sharia, a view that puts him at odds with some efforts by the newly elected Islamists to enshrine religion in even more powerful terms in the country's new constitution. Rather than trying to control the lives of people through the government, Islamist groups should work separately to encourage interpretation of Islam as a way to live, he said.

Mr Al Banna describes himself as Islamist, but believes living by Sharia does not require anything other than a Quran.

"What we need is a more open society," he said. "This is difficult considering the low status of intellectualism in the Arab world."

Religion does not need the state to better lives and bring people closer to Islam, he insisted.

"Allah is the power that will protect man from excess," Mr Al Banna said, invoking one of the 100-odd books he has written entitled Islam is Religion and Community, not Religion and State.

An avid supporter of trade unions and a 30-year lecturer at the Cairo Institute of Trade Union Studies, Mr Al Banna takes the view that Islam is not compatible with capitalism and that religion should help steer society away from a culture of "excess".

"Excess is the fault of western civilisation," he said. "Their civilisation is like a strong motor of the car, but there are no brakes. They are very powerful, can build nuclear energy stations or a tunnel very quickly, but they destroy towns in the process … What we need to do is discriminate between what is right and wrong as a society, not a government."

When politics and religion are mixed, the result is a path to totalitarianism, he said.

"When Christians merged politics with Christianity, they got the Spanish Inquisition."

bhope@thenational.ae

Follow

The National

on

[ @TheNationalUAE ]

& Bradley Hope on

[ @bradleyhope ]