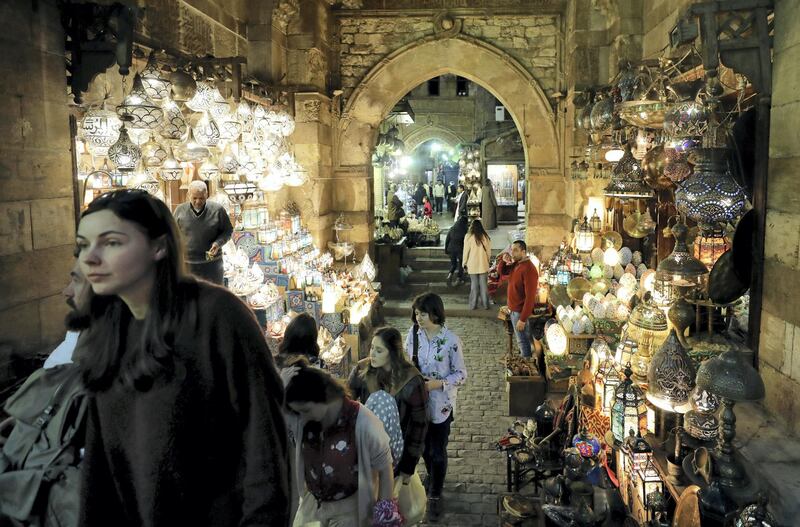

They are back, thronging the narrow alleys of Cairo’s medieval quarter, filling the hallways of the famed Egyptian museum and gazing with a mix of amazement and disbelief at the Pyramids of Giza.

Egypt’s vital tourism industry is rapidly recovering from the slump brought by years of turmoil and violence after a 2011 uprising toppled long-time ruler Hosni Mubarak.

While the number of visitors remains well behind a record 2010 – nearly 15 million – the recovery is astounding and is enthusiastically celebrated by both the government and the millions employed in the vital industry.

Initial figures show that nearly 9 million tourists visited Egypt in 2018, up from 5.4 million in 2016. Revenues from tourism are expected to total $9 billion in 2018, up from $7.6bn the previous year.

It’s too early for any indicative figures for 2019 to emerge, but the year appears to have gotten off to a very good start, judging by the large crowds of foreign visitors at historical sites. Vendors are also positive about their businesses and tour guides who travel across much of the country offer further confirmation.

A senior tourism official said as many as 6 million tourists are predicted to visit Egypt in the first half of 2019 and that the likely resumption of Russian flights to Red Sea resorts later this year could take the number of visitors for the whole year beyond the record number of 2010.

The official added that there were plans to overhaul services in hotels which lost most of their workforces during the slump and to offer tourists more competitive prices.

For now, tourism appears to be showing signs of good health.

“Things are not going badly, but they will never return to what they once used to be,” mused Ibrahim Rashed at his tiny store in the famed Khan el Khalili bazaar in Cairo’s medieval quarter. “Back in those days, we sold so much I could sell the tiles on my shop’s floor to tourists,” he said hyperbolically, as another worker showed a Chinese tourist wooden boxes inlaid with mother of pearl.

Elsewhere in the khan, vendors yelled greetings and invitations to hordes of tourists in Mandarin, Japanese, Spanish and English. At the nearby El Fishawy tea house – arguably Cairo’s oldest – an Oud player serenaded three Gulf Arab youths with classical Arabic songs.

The recovery of Egypt’s tourism industry, which once accounted for 10 per cent of the country's GDP and employed 12 per cent of its workforce, is largely due to improved security and aggressive marketing.

Tight security measures across the country, especially at tourist sites, and a large-scale military campaign against religious extremism, have significantly reduced the number of attacks. There has been just one high-profile terror attack in the 15 months since the killing in late 2017 of more than 300 worshippers at a mosque in northern Sinai, a remote and rugged region that has been the epicentre of a long-running insurgency. That attack took place on February 16, when militants stormed a northern Sinai checkpoint, killing more than a dozen army soldiers.

Meanwhile intermittent attacks targeting foreign tourists or members of the country’s Christian minority have continued. But while they have cast a dark shadow on tourism, they are not known to have caused significant booking cancellations.

The focus on security also means that historical sites are now so heavily policed that negotiating access involves a multitude of searches and checks. Entering the Egyptian museum at the heart of Cairo, for example, involves going through three ID checks and as many metal detectors. Access to the Pyramids plateau involves going through an ID check and a metal detector.

Tour operators are now required to submit to police and diligently observe an itinerary for tourists in their charge. The practice was introduced several years ago, but authorities allowed it to lapse before reviving it following the death of three Vietnamese tourists and their Egyptian guide when their bus was hit by a roadside bomb in Cairo in December.

“They are applying this now with a great deal of rigidity,” said one tour guide with three decades of experience in the business. “Holidays are about freedom. On some days, we learn that the pyramids are shrouded in fog, for example, or traffic is really bad where we are supposed to go, so we kind of do something else. But doing that now means trouble with the police,” said the guide, who wanted to be identified only by his first name, Ahmed.

In some ways, the performance of Egypt’s tourism industry mirrors the trajectory of the country’s political fortunes, something that also lays bare the fragility of the industry. This has been particularly the case since the 2011 uprising, with the unrest and violence that followed it, along with a surge in terror attacks. Combined, they kept the tourists away with disastrous consequences for the economy. Vastly improved security achieved by heavy handed policing and political stability under general-turned-president Abdel Fattah El Sisi appear to have reversed the trend, luring the tourists back.

So badly hit was the industry in the years after the uprising that Cairo’s airport, the country’s main international gateway, was often eerily quiet. Historical sites, including the Giza Pyramids, looked deserted, with hardly any tourists in sight. It was not uncommon for visitors to find themselves alone in a pavilion of the Egyptian museum. Storekeepers selling anything from local perfumes, scarves and alabaster statutes just hung out with nothing to do.

It was even worse in Luxor, the southern city that is home to some of the best-known pharaonic tombs and temples. Some hotels closed, while those which stayed open could only manage a 10 to 15 per cent occupancy. The sight of idle souvenir peddlers and empty gift shops was common. Horse-drawn carts, a favourite with visitors seeking a leisurely tour of the city, stood motionless outside hotels, their owners spending day after day chatting while smoking and sipping sweet black tea.

Beach resorts by the Red Sea fared slightly better, thanks to Egyptian visitors and a small number of western and Arab tourists enjoying sandy beaches and swimming, snorkelling and scuba diving in pristine, rich waters.

Sharm El Sheikh, a southern Sinai, Red Sea resort popular with divers, has just about survived thanks to Egyptian holidaymakers, but it remains far from recovery.

Tourists there vanished overnight after militants in 2015 bombed a Russian airliner out of the sky shortly after it took off from the city’s airport. All 224 people on board were killed. Moscow responded by cancelling all air links with Egypt, a move that took more than 2 million Russians who annually visited Egypt out of the Egyptian market. The Russian decision and Britain’s suspension of its own flights to Sharm El Sheikh just about killed tourism in the city.

Now, news of militants’ attacks in northern Sinai, although they have grown fewer in numbers, are having an impact on the recovery of tourism in Sharm, although the city sits hundreds of kilometres away from the violence to the north.

Russia restored flights to Cairo in April last year but has yet to do the same for Sharm. Britain has not restored flights to Sharm, something that has become a point of contention between the two countries.

There are other issues which, in the eyes of Egyptians employed in the industry, are stopping the industry from realising its full potential.

Egyptians are a proud people whose love for their country can sometimes appear to border on jingoism. While they welcome visitors with open arms, many of them show little tolerance for criticism. So, when a young Lebanese tourist last year released a video laced with profanities in which she slammed Egyptians for sexual harassment while she was holidaying in Cairo, she found herself in jail serving an eight-year sentence for "deliberately broadcasting false rumours which aim to undermine society and attack religions". She was pardoned in September, but the damage was done.

“The damage done by her imprisonment to Egypt’s image as a tourist destination is way more serious than her video,” said Ahmed, the tour guide.

The case prompted the British Foreign Office to issue a damning travel advisory in July, warning Britons visiting Egypt against publicly criticising the government, saying that doing so could lead to a prison sentence. It also warned that making “political comments” about the president or security forces could cause trouble with authorities.

In a separate but equally damaging incident, the British media slammed Egyptian authorities for not dealing appropriately with the near-simultaneous deaths of a couple in their 60s while staying last year at a five-star hotel in the Red Sea resort city of Hurghada. Egyptian authorities initially said the British couple died of natural causes. Faced with a torrent of media criticism and the evacuation of dozens of British tourists staying at the hotel, the Egyptians relented and conducted a serious investigation.

The incident followed another one involving a British woman, who was jailed in 2017 for unwittingly bringing to Egypt locally banned painkillers. She was pardoned last year. The two incidents, however, appear to have had a little effect on the flow of British tourists to Egypt – an estimated 300,000 visited last year – lured mostly by its cheap prices and fair weather.