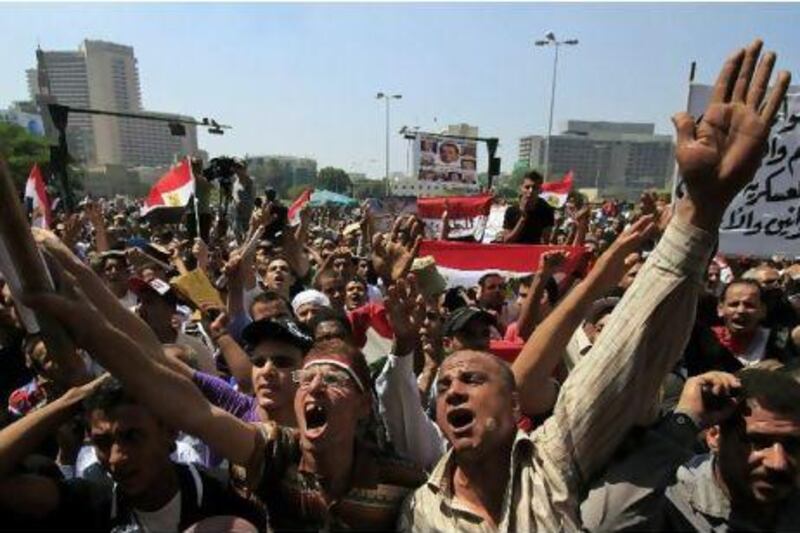

Egypt's ruling generals like to say they are just as "revolutionary" as the youth groups that engineered the uprising that toppled Hosni Mubarak's regime. In reality, their critics claim, they increasingly sound and act like the ousted leader: reviving and expanding the hated emergency laws, trying suspects before state security emergency courts, curbing media freedoms, threatening "decisive measures" to deal with a crisis that "threatens the very body of the state" and speaking of "foreign hands" working behind the scenes to destabilise Egypt.

Ironically, the generals' toughest talk against the country's protest movement since they took over in February was triggered by this month's surprise assault by an angry mob against the embassy of Israel, a nation that is loathed by most Egyptians and was the country's enemy in four wars during a 25-year stretch in the last century.

The military's tough talk was the latest chapter in months of tension over a host of issues between the generals, two dozen men in their 60s and 70s, and the young women and men who orchestrated the uprising, mobilising millions to stage anti-regime protests.

The tension is divisive at a time when Egypt is already destabilised by labour unrest, a surge in crime, rising economic problems and deepening sectarian and ethnic fault lines.

At the heart of the dispute is the military's human-rights record.

Claims of torture of detainees and trying some 12,000 civilians before military tribunals have been thoroughly documented by rights groups.

The military has been accused of operating without enough transparency and not moving fast enough to dismantle the Mubarak regime.

The ruling generals are also criticised for failing to consult on vital issues such as a new election law or who gets to draft a new constitution and when.

In short, the generals keep borrowing more and more pages from Mr Mubarak's manual, with their commitment to democratic rule and freedoms now questioned by youth leaders and many politicians. Some, led by the Muslim Brotherhood, the country's biggest and best organised political group, are questioning the military's willingness to hand power to a democratically elected government and are challenging the generals to announce precise dates for parliamentary and presidential elections.

With hundreds of thousands of hard-core supporters, the Brotherhood can mount a serious challenge to the military if relations between the two continue to slide.

The military insists it has no intention of staying in power indefinitely but wants to make sure that the foundations for stable government are laid down before it steps aside. However, some of the doubts about the military's intentions or its commitment to democratic rule are not without evidence.

Egypt's state-owned newspapers published photographs of Mr Mubarak when he was younger or use heavily altered recent ones that make him look younger.

Now, they are doing the same for Field Marshal Mohammed Hussein Tantawi, the country's military leader who is thought to be in his 70s.

The newspapers routinely publish photographs of him that date back at least 10 years. It is not known if the military is ordering the paper to use more flattering photos, but the practice causes some Egyptians to say Field Marshal Tantawi is acting the same as Mr Mubarak.

Criticism of the military remains a taboo in the state-owned media as it has been for decades. Meanwhile, the independent press is showing little or no reverence to the generals, ridiculing them in cartoons and vilifying them in columns and opinion pages.

Field Marshal Tantawi and his generals have been trying to discredit the protest movement, accusing several of its pro-democracy groups of illegally accepting foreign money, following a "foreign agenda" and disrupting the country's return to normal life.

The military, at least for now, is winning the battle against the protest movement, which it has portrayed as reckless young men and women who use lofty rhetoric but have little useful experience.

Protests called for by the movement are attracting fewer and fewer participants. Friday was a case in point, when only a few hundred turned up at Tahrir Square to protest against the military's revival and expansion of emergency laws, which give police wide powers for arrest and detention.

The military, according to analysts, has taken advantage of the public's frustration with the continuing disruption in the country, rampant crime and the worsening economy to cast the protest movement as responsible for the mess. They have also gone on charm campaigns, distributing free food to families and going out of their way to honour the "martyrs" of the revolution and their families.

Youth leaders say the military is counting on a middle class notorious for its short-term commitment to political activism and its desire for stability to help the generals isolate them. The protest movement, meanwhile, says it is looking to the poor and lower middle classes to fuel the uprising since both have a great deal to gain and little to lose from keeping the heat on the military.

They claim the military may have resorted to dirty tricks in its attempt to discredit them. For example, they say, army troops and anti-riot police were mysteriously nowhere to be found when hundreds of young men spent hours demolishing a security wall outside the Israeli embassy and when some 30 of them climbed 20 floors to the embassy's offices and vandalised them.

The military, they insist, may have allowed the attack to take place to further discredit the protest movement.

Some commentators, however, dismissed the suggestion that the military allowed the attack to happen as ludicrous but offered no evidence to debunk it. Protest groups, meanwhile, have distanced themselves from the incident.

Reflecting the confusion surrounding the attack, a cartoon published on the back page of the independent Al Tahri daily yesterday mockingly suggested that the perpetrators came from a different planet. The more sombre newspapar Al Ahram, for decades a mouthpiece of Egypt's rulers, said in a front page report yesterday that a wealthy businessman whom it did not identify was behind the attack, paying dozens of unwitting teenagers to storm the embassy so as to spread chaos.