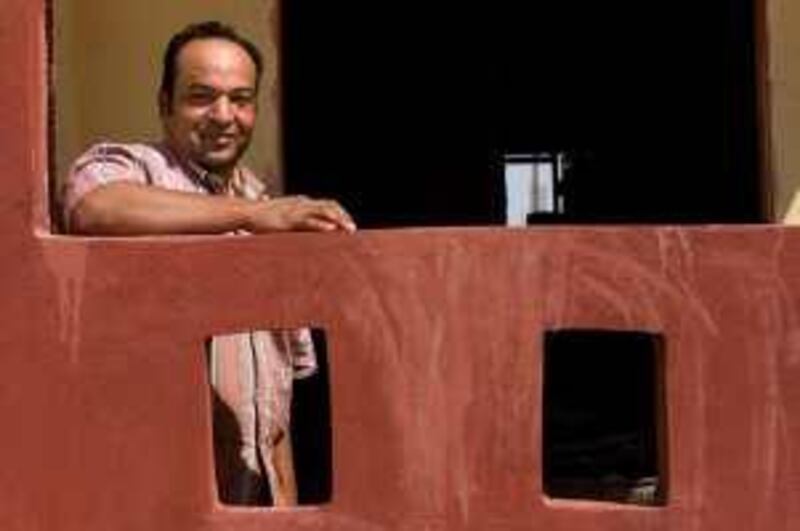

CAIRO // Before he became a homeowner, Ashraf Abaz was a typical Cairene. Well-educated and underemployed, he earns about 900 Egyptian pounds (Dh590) each month as a lawyer in one of the government's bloated bureaucracies. He uses part of his salary to pay for the tiny three-bedroom apartment downtown where he lives with his wife, two children, mother and sister.

That was before he stumbled upon a particularly exciting news article. The government, the newspaper said, will offer plots of land in the capital's desert suburbs at a subsidised rate to any young Egyptian who has the moxie to build his own home. Even the programme's simple name, Ibni Baitak or "Build your home", implied a certain empowering capitalist verve. "I just saw it in the newspapers I read every day. I was so happy when I read this," said Mr Abaz, 38, who hopes to move into his three-storey house in 6th of October City, a well-established "satellite" of greater Cairo, within two years.

"Everyone dreams of having their own house, especially in those new cities that are so far away from the crowds of downtown." Ibni Baitak is the latest experiment in low-income public housing for a country that has known decades of what experts describe as an almost permanent housing crisis. The rapid urbanisation that followed the industrialising economic reforms of the 1970s and 1980s caused a massive housing shortage in Egyptian cities that the government was ill equipped to manage.

Although exact statistics are unavailable, the Egyptian Centre for Housing Rights estimates that 80 per cent of the new homes built between 1970 and 1994 were illegal dwellings for which the residents hold unofficial titles and which are rarely subject to safety inspections. And the problem, say officials at the ministry of housing, is only getting worse. The Egyptian housing market needs about four million new living units, said Mohammed Demardash, a deputy minister of housing and one of the developers of the Ibni Baitak programme. There are 520,000 new marriages each year, according to the housing ministry. These are the people who really need homes, he said.

The need is so acute that during his 2005 election campaign, Hosni Mubarak, Egypt's president, promised voters that his government would build 1.5 million public housing units within six years. With Ibni Baitak, the government may have found an inexpensive way to build adequate housing by sharing costs and construction responsibilities with low-income residents. The programme is open to anyone between the ages of 20 and 40 who has an income of less than 1,000 pounds per month and who does not currently reside in government-subsidised housing.

In its current form, Ibni Baitak has space for about 90,000 participants, nearly half of whom will live in 6th of October City, one of the oldest and most established of Cairo's satellites. In theory, each floor of a building should accommodate one family, and home-builders may elect to rent or sell one or both of the other floors, provided that the home-builder continues to reside on one of the floors. Ten years after the home is completed, the original homeowner is free to sell the whole lot.

It is a prescription for turning low-income Egyptians into small-scale investors and landlords, said Ayman Ashour, a professor of architecture and urban planning at Ayn Shams University in Cairo and one of the designers of Ibni Baitak. "This is the first lesson we gained from the informal settlements established in Cairo or in Egypt, that the low-income and middle-income people and investors have the capability to develop houses on their own, by themselves," said Mr Ashour, who added that the designs for Ibni Baitak mimic the simple, uniform styles of the illegal homes that can be seen throughout the country.

By taking their design cues from the informal settlements, Mr Ashour and other urban planners hope to one day make them obsolete. "It's the characteristics of informal houses, but in the right way. Of course we are not going to develop informal settlements any more, but we're basing this project on our understanding" of the preferences of these small-scale investors whose illegal developments house much of Egypt's urban population.

Although Ibni Baitak may be a boon to new families and young Egyptians, the programme also provides a kind of free lunch for the government, which has been trying for years to develop the desert land that forms the bulk of the country's geography. Ninety-nine per cent of Egypt's 80 million-strong population lives on the 5.5 per cent of the country's land that straddles the Nile River Valley, according to a report by the Rand Corp in 2000.

Since the homeowners are financially responsible for the development, the project offers an inexpensive incentive for Egyptians to leave the Nile Valley cities, which are some of the most densely populated conurbations in the world. Until the first 4,780 houses in 6th of October City are completed in January, it will be impossible to evaluate the success of the project. But for the thousands of Egyptians like Mr Abaz, who soon hope to live the once-impossible dream of owning their own three-storey houses, Ibni Baitak is already an unequivocal success. Though he still has two years before he expects to move in, Mr Abaz gushes with praise for the Egyptian government and its controversial, divisive president.

"It was the intention of the government to have the youth take responsibility for themselves instead of just building a house and giving it to them," said Mr Abaz, gushing with obvious admiration. "It's a very happy feeling." mbradley@thenational.ae