Just over 70 years ago, Naziha Al Dulaimi was appointed minister of municipalities in Iraq, becoming the first-ever woman in the Arab world to hold a cabinet post.

Al Dulaimi’s success set a precedent, but her achievement was not the political turning point for Arab women that many hoped it would be. Instead, it marked the beginning of a slow shift that saw some Arab governments begin to make way for women over time, but in 2021, there’s still a long way to go.

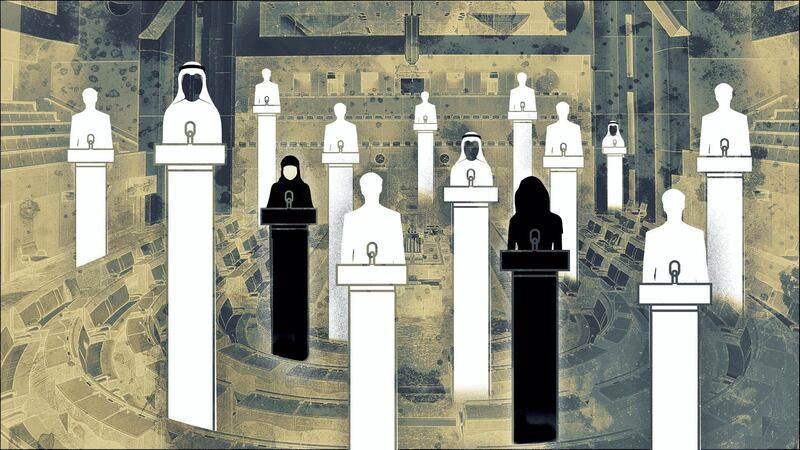

The latest figures continue to reflect a sizeable gender imbalance in politics at local and national levels across the region.

According to data presented by the Geneva-based Inter-parliamentary Union (IPU), the Middle East and North Africa region continues to have one of the lowest percentages of female representation in national legislatures worldwide.

Women make up, on average, just 17 per cent parliaments in the region, compared to 40 per cent in Nordic countries and 27 per cent in both Europe and the Americas.

Some improvements have been made, however, to challenge traditional perceptions of what a decision-maker looks like in the region.

The most recent progress is this month’s appointment in Egypt of 14 more women in the House of Representatives, the lower chamber of parliament.

This follows the election of 148 women to the legislature last year.

Women now account for more than a quarter of the chamber's 596 members, totalling 162 compared to just two lawmakers in 1956 when Egypt granted women the right to vote and run for elections.

It’s a significant increase from the country’s previous legislature, which had only 89 women and follows the success of female candidates in the latest elections and a rise in female political appointments made by the president.

Calls for change from women’s rights activists in the country prompted changes to Egypt’s electoral regulations in recent years, including a 2014 amendment to the constitution that tackled quotas for women.

"This is an unbelievable outcome," Neveen El Tahri, one of the newly appointed lawmakers, told The National, discussing the latest elections.

The Harvard-educated businesswoman cites an encouraging trend in her country that’s seeing more entities adopt gender-balanced attitudes.

“The Financial Regulatory Authority introduced last year a mandate for all listed companies to include at least one woman on their boards,” she added.

But Egyptian women are still working against forces that hinder their path politically with cyberbullying, harassment and discrimination among the tactics used to silence and intimidate women in a society where many still subscribe to conservative gender norms.

Data gathered in the country for the International Men and Gender Equality Survey (IMAGES) in 2019 shows that two-thirds of Egyptian men opposed women occupying positions of political authority and half of those surveyed men believed that politics should be a "men-only" area.

Chief among the obstacles to Egyptian women’s representation in politics are their lower rate of involvement in political parties, lack of childcare, lack of professional networks and a disadvantageous financial position, according to the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women, also known as UN Women.

Elsewhere in the region, the UAE saw the largest increase in women’s representation in legislation in terms of percentage, with 20 female and 20 male representatives on the Federal National Council following a 2018 presidential decree.

The UAE climbed eight positions on the UN Development Programme’s Gender Inequality Index, ranking first in the Arab world and 18th globally in 2020 for commitment to advancing women's rights.

By comparison, the UK ranked 13th while the US was 17th.

In Iraq, the post-2003 Iraqi constitution decrees that a quarter of the nation’s 329 parliamentary seats are reserved for women, while in Saudi Arabia, there’s a 20 per cent quota for women in the kingdom’s legislative branch, the Shura Council.

Two years on the road: how life has changed for Saudi women

Kuwait, which does not have a quota system, saw a setback last year after the country’s only female MP, Safa Al Hashem, lost her seat in polls. The all-male body elected in December 2020 was seen as a blow for women’s rights in the country after 29 female candidates lost the race.

But activists in the region, where female politicians have often been consigned to less prominent posts with a focus on family ministries, have pointed out that being in parliament doesn’t necessarily mean being heard, particularly when they remain a minority in most Arab political systems.

Lina Abou-Habib, a MENA adviser to the Global Fund for Women, says it isn’t acceptable to see women squeezed into just 25 per cent of the room.

"Despite advances made in closing the gender gap, women's ability to penetrate and influence the political domain remains limited," she told The National.

“These women are still in small numbers, with many being part of patriarchal parties in power and are rarely connected to the feminist movements. As such, they rarely, except in few cases, carry a feminist agenda for change and for gender equality.”

Traditional gender roles in the Arab world continue to constrain women’s mobility in the public sphere, adds Ms Abou-Habib, who is a staunch supporter of the gender quota system in Arab parliaments.

“I know that this is a controversial issue but we need a shock therapy in order to change the landscape of politics in the region,” she said. “Yes, I am aware that a quota system may not bring in the most competent candidates but I think we all realise that men's incompetence is never questioned or challenged.”