Farida badly wanted a hug on her 22nd birthday last week. She did not get one.

Her parents and younger sister chose to put social distancing above family tradition. Her mother, however, made strawberry cheesecake, Farida’s favourite dessert, to mark the occasion.

“I know it’s a fluffy thing to say, but I did want a hug,” Farida said.

The Dutch-educated handicraft artist, who lives with her family in an upscale Cairo neighbourhood, celebrated her big day online with her closest friends.

“I just moved from one sofa to another at home for a change of scenery. When this thing is over, I will never take anything for granted,” she said.

An outbreak of the deadly coronavirus in Egypt, whose 100 million people make it the most populous Arab country, has upended people’s lives in a multitude of ways.

It has changed social practices, altered lifestyles and affected many of the things Egyptians have long taken for granted.

For some, the crisis has triggered soul-searching.

“To me, it’s all good. Death just comes at any rate. If you don’t die today, you die tomorrow,” mused Ahmed, 55, a father of three who has suffered from a heart condition for several years.

“Over the last few years, I buried my father and my mother. Last month, I buried my brother who died of cancer,” Ahmed said.

He recounted how mourners wearing masks showed up for a quick prayer at the hospital where his brother died, and his struggle to organise a wake during a ban on gatherings.

“This corona thing is making me treat people better than I used to," said the private-sector employee. "I try not to upset anyone anymore. Life may prove too short for all of us.”

Many changes brought about by the pandemic – some subtle, some jarring – are best observed in Cairo, a city of more than 20 million people. It has the country's largest share of coronavirus-related fatalities and infections – 164 and 2,190 respectively, according to the latest figures published on Monday night.

A sprawling, Nile-side metropolis where squalor and well-heeled society awkwardly coexist, Cairo has a reputation for being a lively city that does not sleep.

It is home to a wide range of entertainment without equal elsewhere in the country but stifling pollution levels, constant traffic congestion and a unique brand of rudeness from its inhabitants make living there something of a reckless proposition.

Making the social distancing measures tougher to accept is the gregarious nature of Cairo’s residents, who greet each other with hugs and kisses and many of whom routinely spend hours at tea houses and cafes chatting over black tea, coffee and smoking from waterpipes.

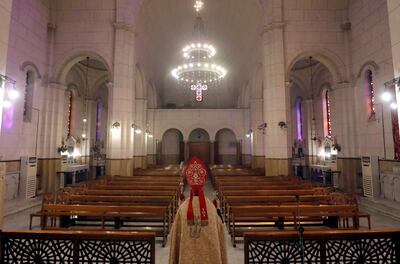

The city has been under night-time restrictions on movement for close to three weeks. Its mosques and churches have been shut along with schools, universities, restaurants, cafes, gyms and sports clubs. International air travel has also been halted.

The measures transformed Cairo seemingly overnight as streets that were usually choked with pedestrians and traffic became eerily quiet. On the bright side, the air is much cleaner.

The new-look city and the deepening fear of infection by Covid-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, has come at a time when Egyptians were preparing for Easter on April 19 and the start of the holy fasting month of Ramadan less than a week later, the two most coveted occasions in the Coptic Orthodox Christian and Muslim calendars and a time of spirituality and giving.

In this spirit, the pandemic has brought out some of the kindest traits in Egyptians, from helping day workers who can no longer find employment to feeding the city’s tens of thousands of street cats and dogs who have been going hungrier than usual under the present conditions.

Combating ignorance of the methods in which the disease is transmitted, animal lovers have launched a vigorous social media campaign to reassure pet owners that their cats and dogs do not pose a threat.

Thanks to self-isolation, however, pet owners say their cats and dogs are having the time of their life, with their human friends hardly leaving their homes.

"Ramadan will give me the motivation I need because I intend to give part of my profits to charity. This will take me out of the flat loop of living and working at the same place," said Farida, who is self-employed and works from home. "Another plus these days is how happy Phoebe, my Yorkshire Terrier, is because we are around every day."

Cairenes, on the other hand, have shown their appreciation for the thin traffic and cleaner air and taken to the streets in droves, jogging and cycling, painting unfamiliar scenes of a city where doing either can fairly be labelled life-threatening.

But the pandemic has also brought to the surface some of the city’s darker traits, like greed and a lack of concern for others.

Cairenes with deep pockets have been panic shopping at supermarkets since the coronavirus restrictions were announced last month, emptying shelves and denying those who can only afford much less the chance to buy essentials.

Retailers seeking a bigger profit margin have significantly marked up the price of much-in-demand surgical masks, sanitisers and alcohol.

Fahd Hassan, a 35-year-old government employee and father of two, laments that he has so far spent a total of 500 pounds (Dh116) on Covid-19-related items – more than a third of a month’s salary.

“These items are sold at twice or three times their normal price,” said Hassan, who dabbles in literary writing. “I want to write about the fear and mystery that’s engulfing Cairo these days, but I am consumed with concern about my wife and children.”

Fearing an economic meltdown that would wipe out gains from years of painful austerity and reform, the government has gone to great lengths to strike a balance between protecting the population against Covid-19 and keeping at least some sectors of the economy running to prevent millions of workers and their families from going hungry.

Egypt's vital tourism sector has been hit the quickest and the hardest, a particularly harsh blow in a year that was shaping up to be the best on record until the coronavirus struck. Hundreds of thousands employed in the labour-intensive sector are now losing their jobs or suffering pay cuts.

Ahmed, a veteran French-speaking tour guide, was on a Nile cruise in southern Egypt with what turned out to be his last group of tourists when word arrived that they would have to be sent home on the first available flight.

With scheduled international flights later halted, the father of two became jobless, just the same way he was when tourism almost completely dried up in the years of turmoil that followed the 2011 uprising that toppled long-time ruler Hosni Mubarak.

“I sat the children down and explained to them what was going on,” he said. “I told them that we will need to economise and do without some things, and they understood. Now my two chief challenges are boredom and money.”

Although self-isolation has kept families and friends apart, applications like FaceTime, WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger have become popular modes of contact.

The elderly, widely seen as the most vulnerable, are kept away from younger members of the same family for fear of infection, leaving children without the love and care provided by grandparents.

School-age children are now constantly at home, with online schooling taxing parents who had grown accustomed to having little to do with the education of their offspring.

Children who are into sports are coached online, with parents complaining that the sessions are too short, leaving their little ones with energy to spare and them with the tough task of keeping them busy the rest of the day.

“I feel that all my hard work with my daughter is lost,” said Marianne, mother of a promising seven-year-old gymnast who lives in central Cairo.

“Staying at home has spoilt her. Now she wakes up whenever it pleases her and goes to bed late. None of the discipline instilled by going to school every day is left,” she said.

“Her days used to be packed before the coronavirus struck. She is now missing all the activities she did with her friends and she cries for no reason. The other night she cried because she did not think I tickled her enough before she went to sleep.”